Introduction

This past week was filled with highs and lows in my 8th grade social studies classes. It started out on a high note as I attended the Ohio Council for Social Studies annual conference in Columbus. I always look forward to this conference as a chance to connect with fellow teachers, discover new ideas and resources, and reignite my passion for the subject. However, when I returned on Tuesday morning, I quickly realized through a short quiz and student survey that my students were still struggling to grasp key concepts from our unit on the causes of the American Revolution. This kicked off several long days of reteaching the material in new ways, providing additional scaffolding, and letting students demonstrate their learning through creative assessments. It was frustrating to have to hit pause on the unit timeline, but I’m glad I took the time needed to ensure real comprehension.

Monday – Frayer

Tuesday – Kevin Roughton created (Parents), Enlightenment Revolution

Wednesday – Assessment Choices

Thursday – 3xCER

Monday – OCSS

On Monday, I headed to downtown Columbus early in the morning to attend the Ohio Council for Social Studies (OCSS) annual conference, which is always one of the highlights of my year. I started off the day by presenting on two topics – using Eduprotocols to engage students, and harnessing AI tools in the social studies classroom. I enjoy presenting as it pushes me to distill my best teaching practices. The audience had thoughtful questions and ideas to further improve my strategies.

After my presentations, I attended a fascinating session all about incorporating ChatGPT into the classroom led by an educator from the Cleveland area. With ChatGPT exploding in popularity among students, it’s clear that AI is here to stay, so I appreciated her perspective on establishing citation methods and protocols. Rather than banning it, she argued we should teach students how to utilize it as a tool ethically. I’m still pondering how to adapt my own policies.

My other favorite session was on leveraging the Library of Congress digital archives for primary sources. The presenter took us through the site and had us explore sets of WWI propaganda posters in a scavenger hunt. While the session was interesting, I found myself wishing for more examples of classroom strategies to actually engage students with the amazing primary source collections. For instance, I love the “retell and rhyme” Eduprotocol my co-author Scott Petri uses – students read a source, then recap the key facts and events in a rhyming poem, keeping track of how many details they included. This interactive approach really sticks with students.

Since I knew I would be absent all day, I left lesson materials for my students to complete independently. I assigned them to analyze the various British taxes and acts from our unit by filling out a Frayer Model chart, listing facts like the purpose, colonist reactions, violations of natural rights, etc. The Frayer Model is a great eduprotocol because its simple format means students can work on it independently. I was pleased to see that over 80% of my students across 5 sections had completed the assignment when I checked on Tuesday morning.

I also left a Gimkit review game on the causes of the Revolution for them to play. Gimkit combines gaming elements with quiz questions for engaged review. However, the class average was only around 70%, suggesting there were still gaps in student understanding I needed to address.

Tuesday – Reteaching

When I returned to class on Tuesday morning, I decided to immediately assess retention again using the same quiz questions, but transferred into a Quizizz format. I’m loving Quizizz’s new AI features, like the ability to upload question banks from other platforms instantly. The Quizizz results confirmed that students were still shaky on being able to explain British acts like the Quartering Act and link them to Enlightenment philosophy concepts like natural rights and social contract theory.

This data showed me that further reteaching was necessary. I started class by surveying students directly, asking them to rate their comfort level with the content on a scale of 1-5. The results skewed heavily towards the lower numbers, with many rating themselves a 2 or 3. When asked what specifically was confusing, common answers included:

- Connecting Enlightenment ideas to anger over British acts

- Explaining how the French-Indian War changed the British-colonial relationship

- Describing the purposes of specific British taxes and policies

Armed with this student feedback, I knew I needed to rework my approach and reteach the connections between Enlightenment ideology, like social contract theory and natural rights, and specific oppressive British legislation like the Proclamation Line and the Quartering Act.

I decided to use a creative metaphor lesson from teacher Kevin Roughton where the buildup to the American Revolution is compared to conflict between increasingly rebellious teenagers and their parents setting harsh rules. The analogy really seemed to help students understand the gradual progression of events and why the colonists became outraged enough to revolt. I could see the lightbulbs going on as we talked through the metaphor!

I also put together a quick slideshow presentation as another way to clarify the relationship between Enlightenment thinking and colonial anger. My goal was to remind them how Enlightenment philosophers introduced new radical ideas about government deriving power from the people rather than divine right. I highlighted examples of British acts that violated colonists’ conceived natural rights, like economic restrictions and housing soldiers in their homes. Then I directly asked questions like: Did colonists have representation in British Parliament? Could they vote out these leaders who were levying unfair taxes and policies? When I framed it this way, it clicked for many students how the colonists felt they had no choice but to revolt when their ideas of government based on social contract and natural rights were being breached. The presentation seemed effective in tying everything together.

Wednesday – Assessment

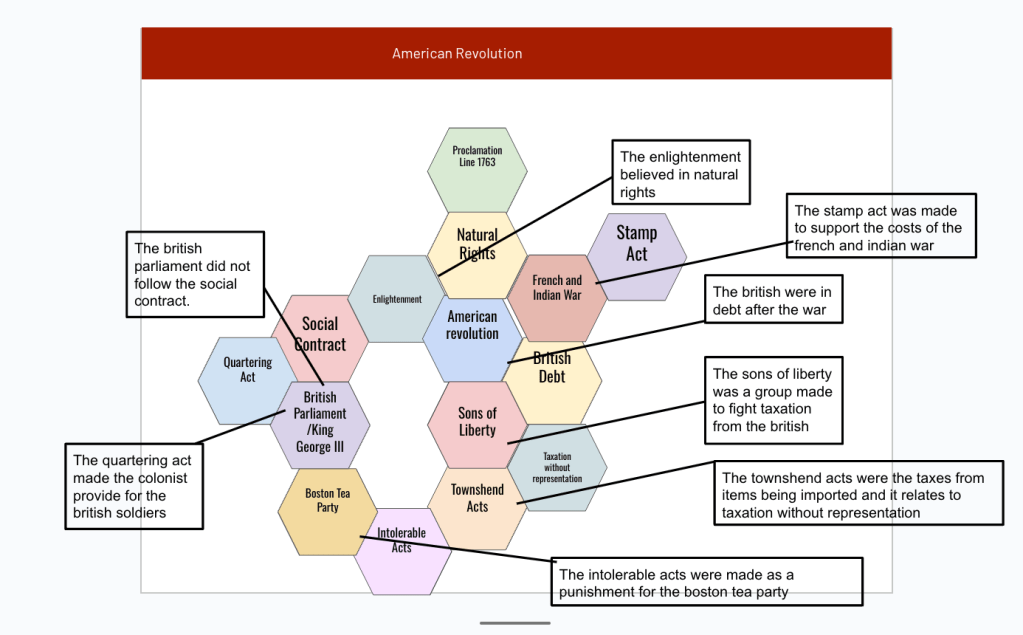

At this point, we had gone over the projected unit time, but I refused to move forward if students were still struggling with the core concepts. On Wednesday, I introduced a creative summative assessment option for students to demonstrate their learning. They could choose between using story dice to narrate the events leading up to the Revolution with drawings, or a hexagonal learning activity where they had to connect Enlightenment concepts with matching British policies. Both hands-on options allow students to showcase understanding in a visual way that appeals to different learning styles. For some of my students with IEPs, I modified the hexagonal activity by having them complete just a portion of the timeline with a few matched pairs.

In my instructions, I provided suggestions of key events and concepts I wanted to see, such as:

- Explaining how the French-Indian War changed the relationship between colonists and Britain

- Identifying and accurately describing at least 3 British taxes/acts

- Connecting an Enlightenment ideology like natural rights to colonist anger

As I monitored progress and checked in with individual students, I noticed some were still struggling with properly identifying acts like the Stamp Act or connecting violations of rights to Enlightenment theory. With prompting, many were able to grasp the concepts and correct their work, which was really encouraging to see.

Thursday – CER Practice

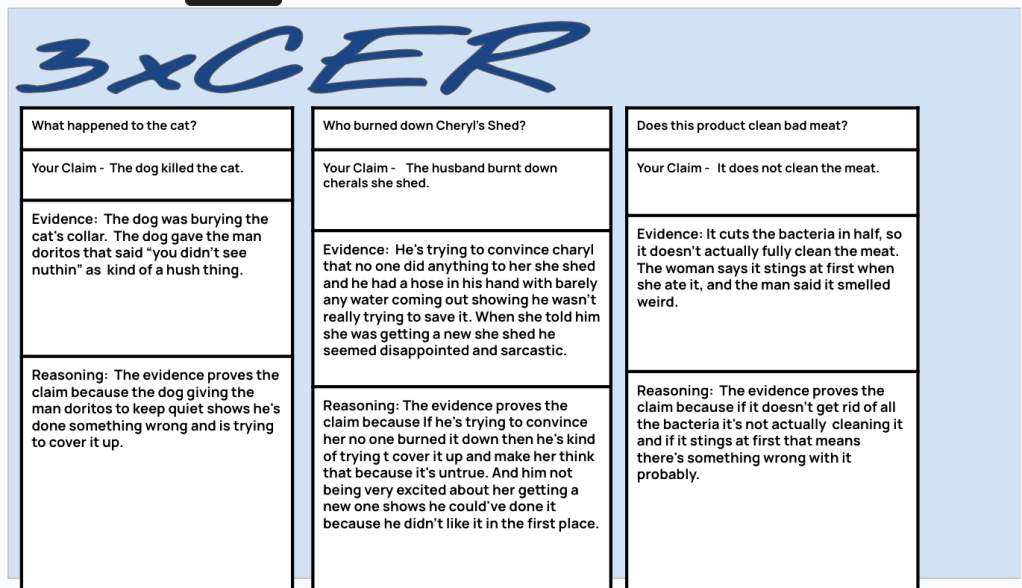

Some classes needed more time on Thursday to complete their Revolution storytelling assignments, so I allowed a grace period for finishing up. In my sections that were ready to move on, I introduced our next topic by having them practice evaluating evidence and making claims by analyzing commercials – a fun critical thinking exercise they enjoyed as a lead-in to our unit on the Sons of Liberty and using Claims-Evidence-Reasoning frameworks to analyze historical events.

Conclusion

This week was challenging when my students didn’t initially grasp the concepts I thought I had taught effectively. My plans went out the window as I pressed pause on the curriculum timeline to rework my approach through presentations, metaphors, surveying student needs, and offering creative assessment choices. As teachers, flexibility is so key for reflection when something isn’t working, and I’m glad I took time for reteaching despite the unit creeping longer than intended. The week was taxing but rewarding. My students’ final projects demonstrated real comprehension of the complex factors driving colonial rebellion, which made the extra effort worthwhile. I’m reenergized after this reflective process and have new ideas to try for engaging learners who need different avenues. As next week launches new material, I feel confident we built a strong foundation.