This week was built around a simple idea: use clear EduProtocols to help students think deeply about how power works.

We used Frayers to activate prior knowledge. CyberSandwich to frame historical tension. My Short Answer to sharpen explanations. Sketch and Tell to make ideas visible. Archetype Four Square to push evidence-based thinking. Building Thinking Classrooms to rank, justify, and disagree. EdPuzzle to anchor content before diving deeper.

The focus stayed tight. How does power get limited? How does it get tested? How does it stretch?

Monday

Beginning With the Safeguards

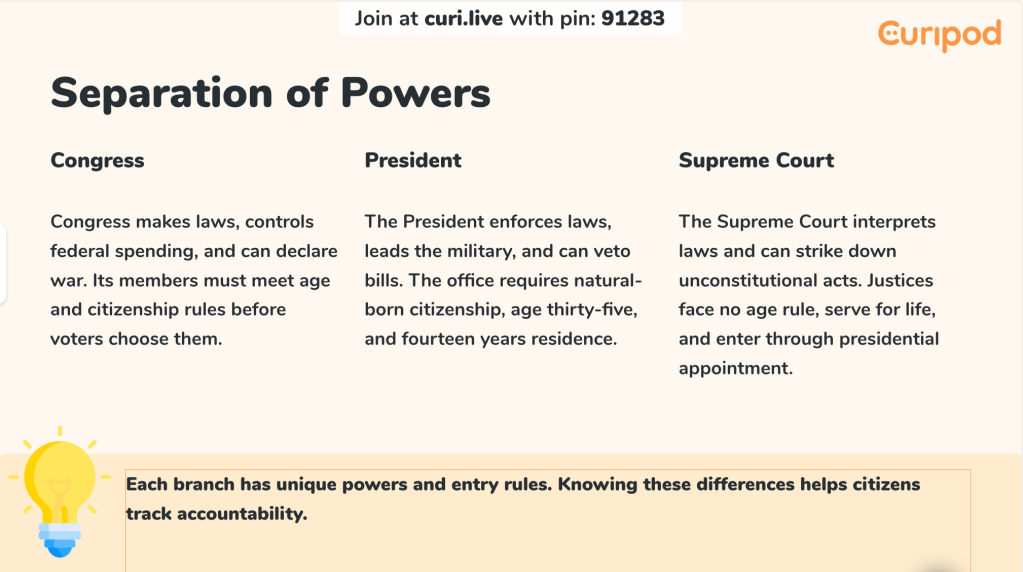

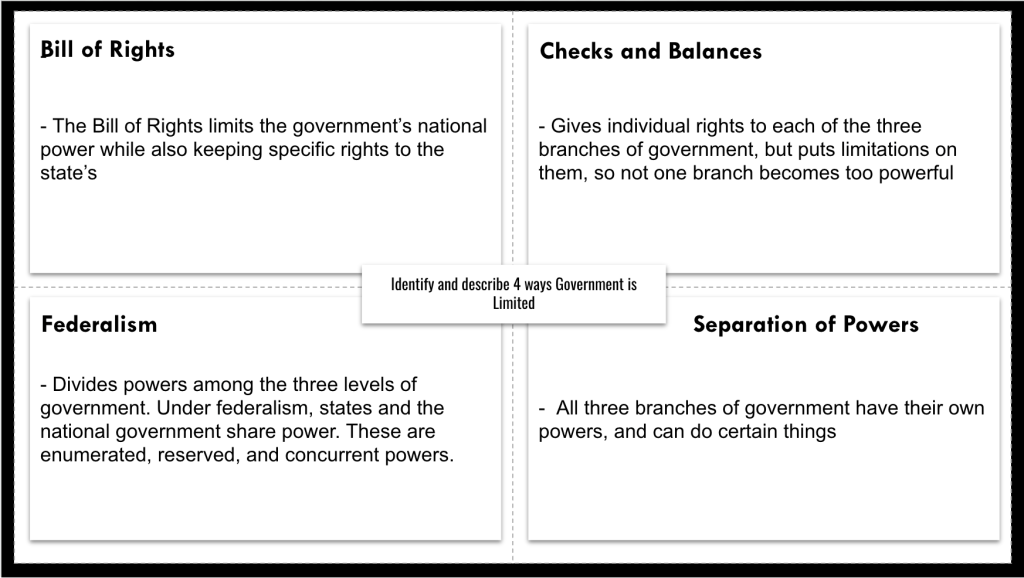

We started Monday with a Frayer built around one question: How did the founders ensure we had a limited government? No notes. No textbook open. Just retrieval.

Students filled the boxes with separation of powers, checks and balances, federalism, protecting rights, and the Bill of Rights. The ideas were there. The language was automatic. That told me the repetition over the last few weeks worked. The Frayer was not the lesson. It was the foundation.

The Pivot to Unlimited Power

Once students had clearly named the safeguards, I shifted the question. What happens if those safeguards disappear?

Could separation of powers be ignored? Could Congress be dissolved? Could courts be weakened? Could rights be suspended? That is where we moved into Alberto Fujimori.

Students read about how he was elected president in Peru, faced opposition from Congress, and then dissolved Congress, rewrote the rules, and concentrated power in his own hands. The contrast was immediate. Everything they listed in their Frayer could be undone. A republic does not have to erode slowly. It can change quickly when one branch removes the limits.

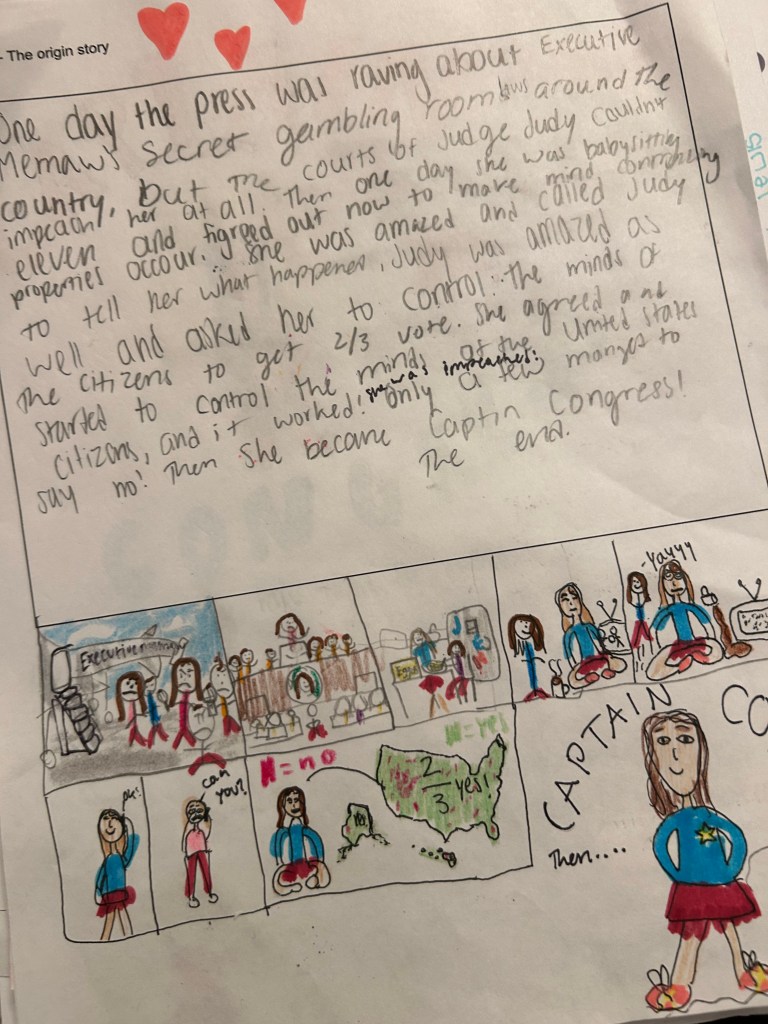

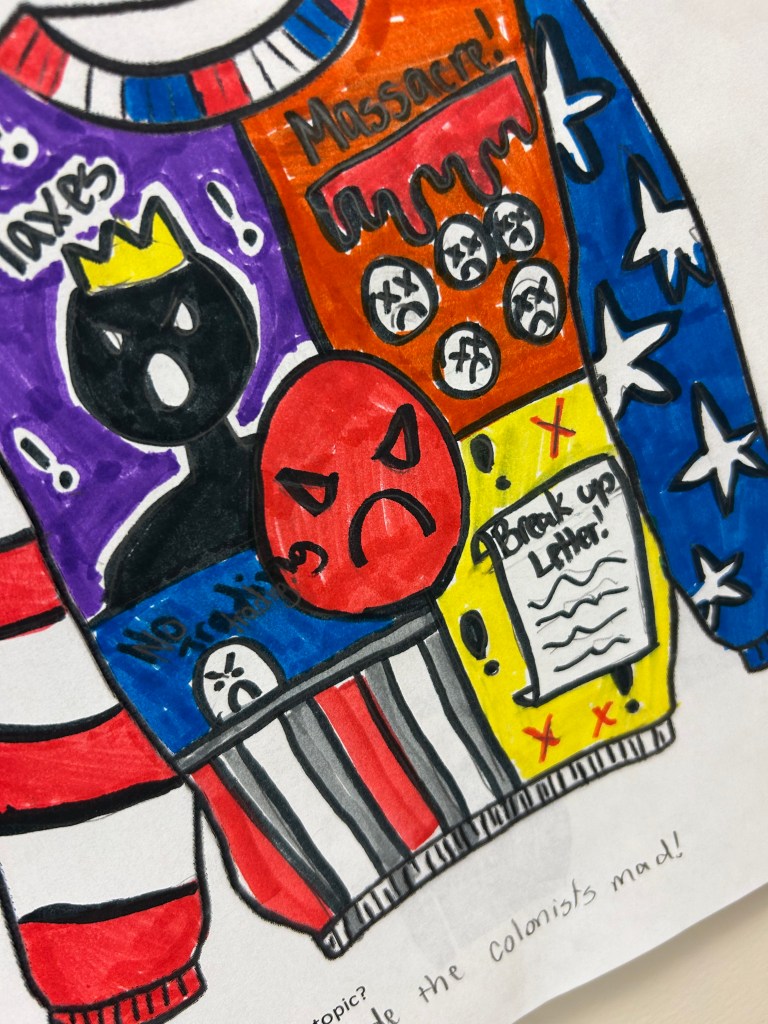

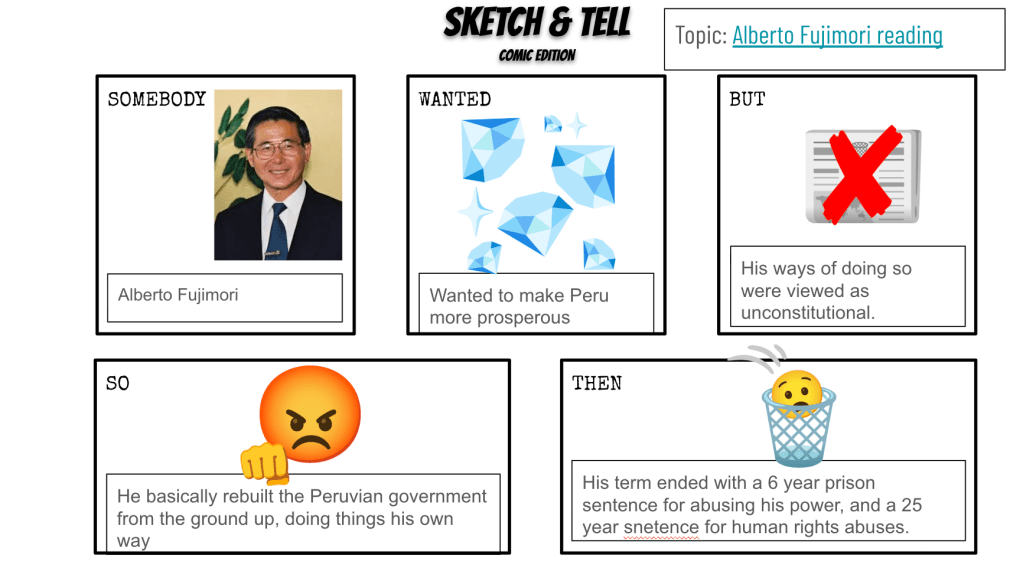

SWBST Sketch and Tell

After reading, students used a Somebody Wanted But So Then Sketch and Tell to map the story.

Somebody was Fujimori.

He wanted to push through his ideas.

But Congress opposed him.

So he dissolved Congress and rewrote the rules.

Then power concentrated and rights were abused.

The structure forced cause and effect. Students clearly identified the turning point. Dissolving Congress was the snap.

They were not just summarizing. They were tracing how power shifted.

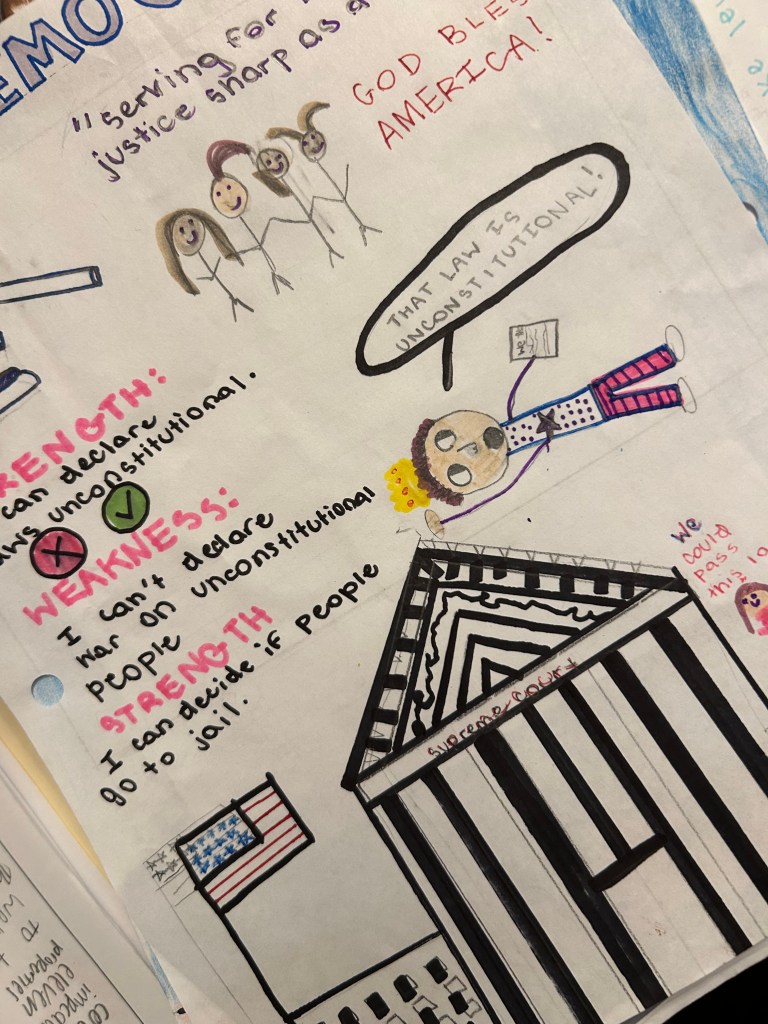

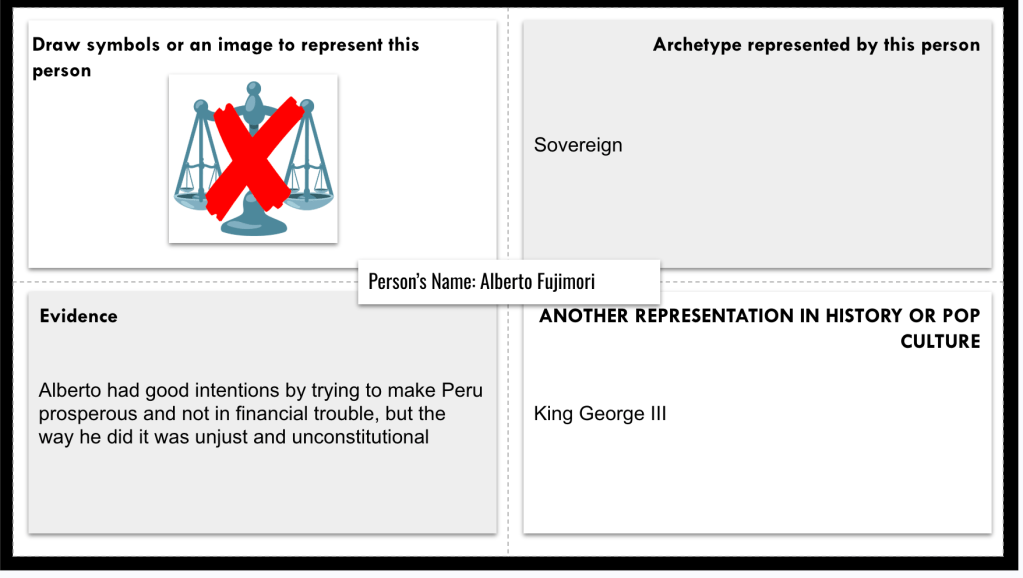

Archetype Four Square

We finished with an Archetype Four Square focused on Fujimori.

Most students identified him as a Ruler who drifted into Tyrant territory. He fits the Sovereign archetype because he sought control, order, and authority. However, when he removed checks, silenced opposition, and rewrote the system to consolidate power, that archetype shifted toward its unhealthy extreme.

The evidence supported it. He dissolved Congress. He weakened the judiciary. He ruled without meaningful restraint.

Students connected him to other historical figures who centralized authority and bypassed institutions. The archetype helped them see the pattern. When one person removes limits, the system tilts.

Closing the Loop

We ended by returning to the Frayer from the beginning of class.

Separation of powers.

Checks and balances.

Federalism.

Rights.

Those ideas were no longer abstract. They were safeguards against what we had just studied. Students began the day explaining how limited government works. They ended it understanding how fragile it can be.

Tuesday

Tuesday was about clarity. Not grades. Not stress. Clarity.

Instead of giving a traditional unit test, I re-ran the same 10-question assessment students took a few weeks ago at the start of the Constitution unit. No warning. No study guide. Just retrieval.

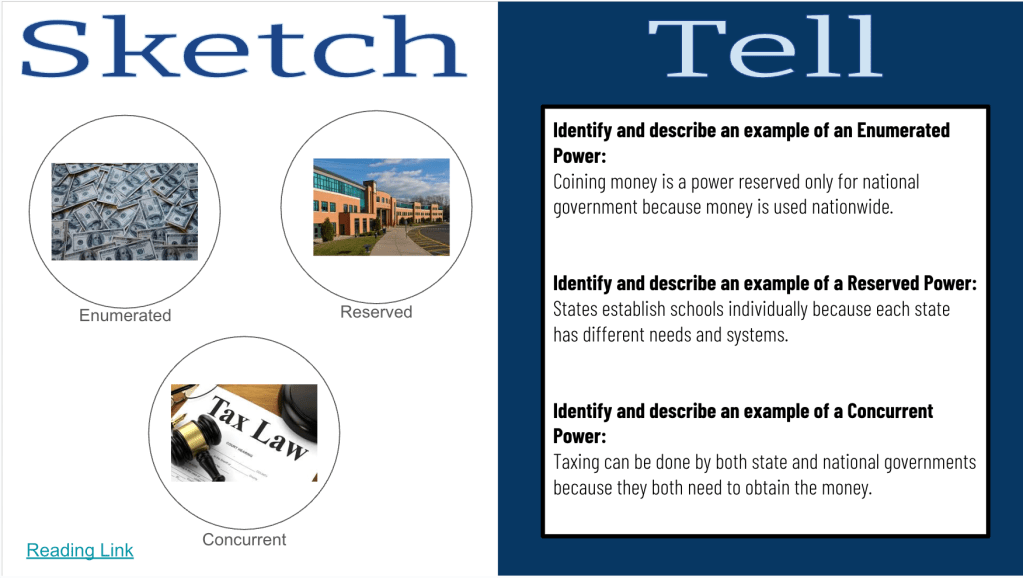

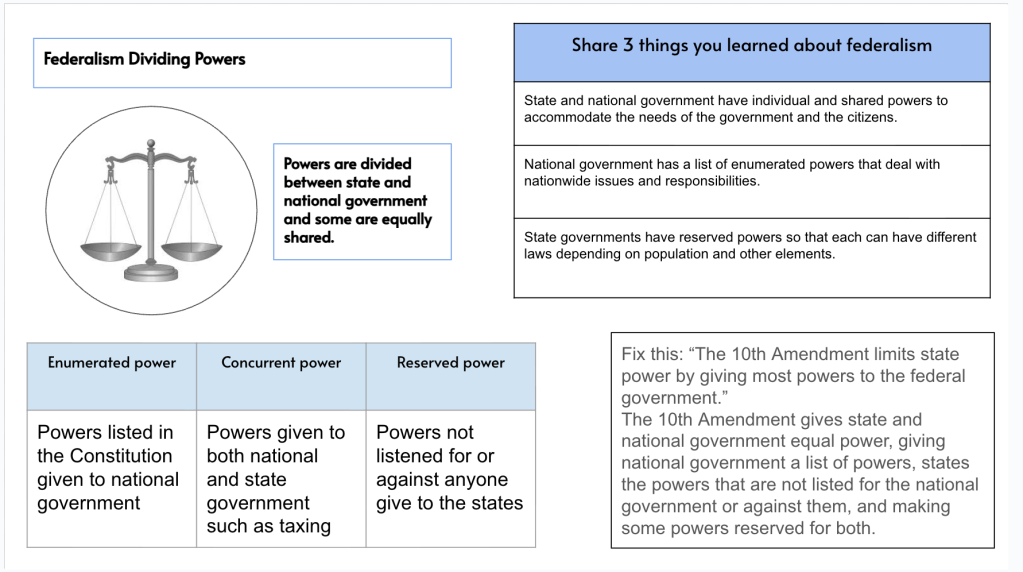

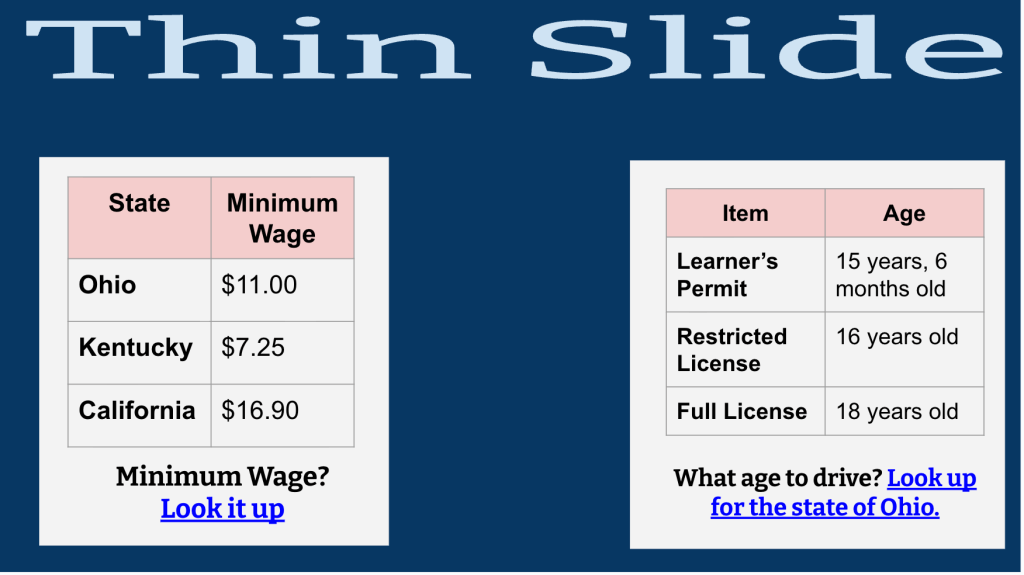

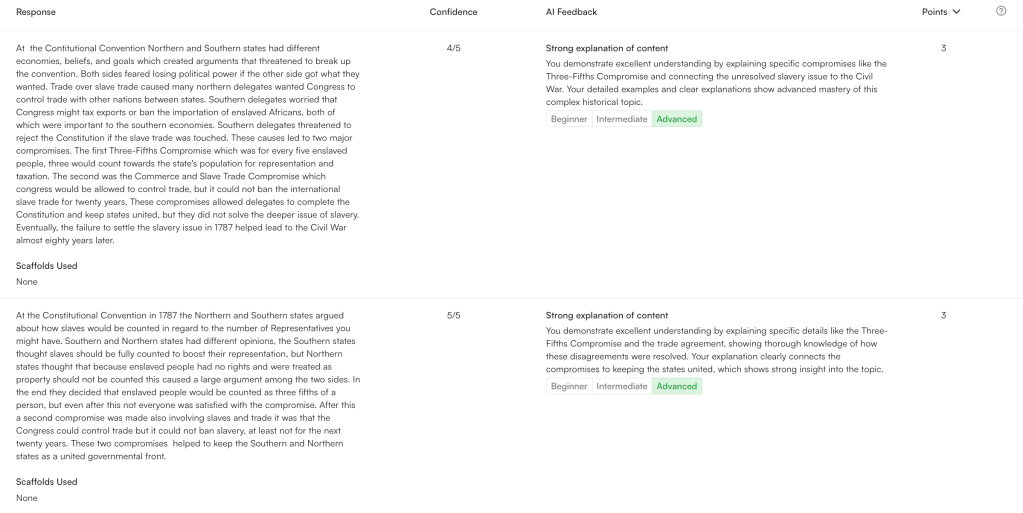

The first time we took it, the averages were low. 2.1 out of 10. 2.5. 3.0. 2.8. 2.7. On Tuesday, those same classes scored 8.1, 7.8, 7.0, 8.3, and 8.7. That shift mattered. It showed that the repetition across weeks was doing its job. Fast and Curious. Thin Slides. Frayers. Sketch and Tell. Cybersandwich. Structured retrieval built into daily routines. Students were not surprised by the format. They were not guessing. They were recalling ideas they had worked with repeatedly in different ways.

Keeping the assessment low stakes removed pressure and allowed the data to reflect understanding instead of anxiety. When students saw the new averages on the board, there was a noticeable shift in posture. They could see their own growth.

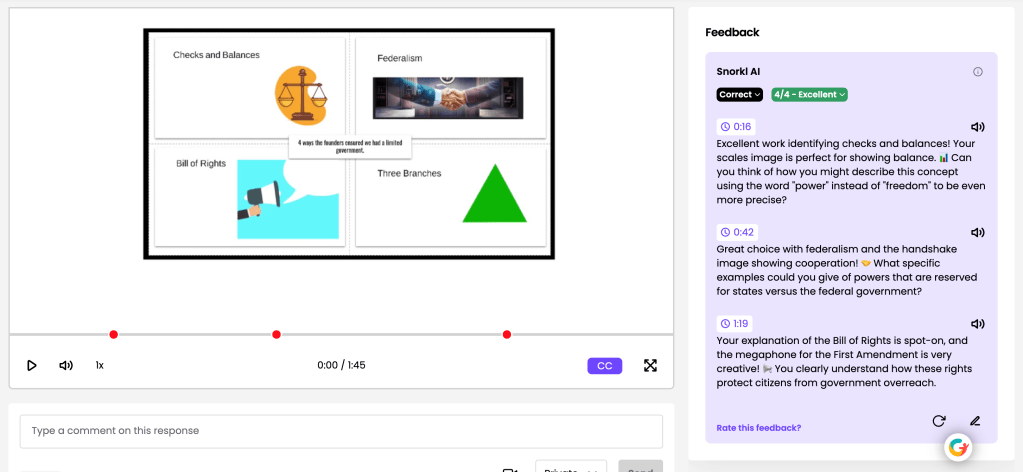

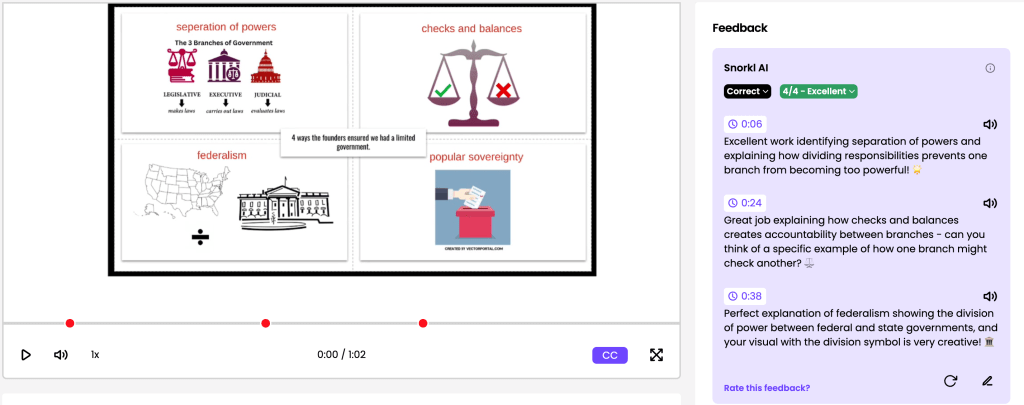

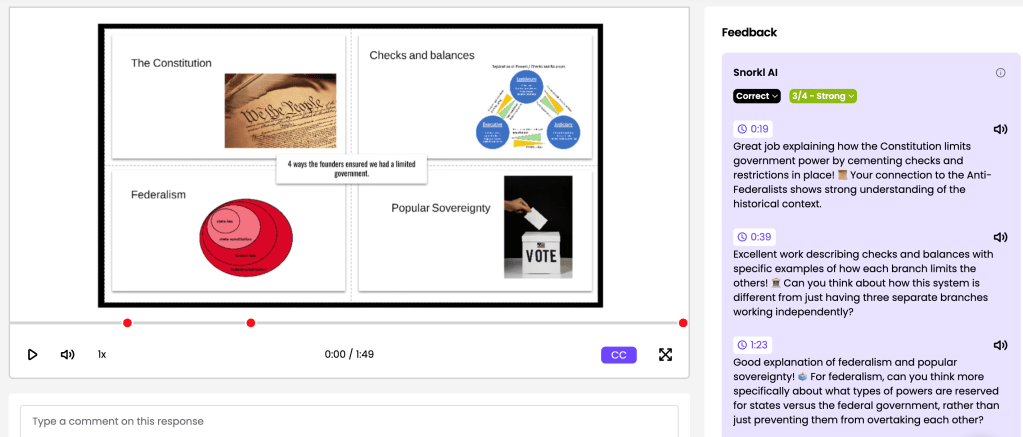

After the retrieval check, we moved into the graded assessment, but I wanted explanation instead of memorization. I uploaded a Frayer template into Snorkl and asked students to treat it like four Thin Slides in one. Each quadrant required one picture and one word or phrase connected to our guiding question: How did the founders ensure we had a government with limited power?

Separation of powers.

Checks and balances.

Federalism.

Popular sovereignty.

Bill of Rights.

The constraint was intentional. One image forces students to decide what truly represents the idea. One phrase forces precision. There is no room for vague language. The structure did the cognitive work. Students were not figuring out what to do. They were thinking about what limited government actually means.

The final step was a one-minute mini Ignite Talk recorded in Snorkl. Students had to explain how all four pieces worked together to limit power. This is where understanding becomes visible. Students cannot speak clearly about a system for a full minute if they only have surface knowledge. They have to connect ideas. They have to sequence their thinking. They have to explain cause and purpose.

Snorkl provided immediate AI feedback, which pushed students to clarify examples and tighten explanations. Many students re-recorded multiple times. Not because they were told to, but because they saw where their thinking needed refinement.

Each attempt strengthened their explanation. Each round forced them to be more specific. Each revision moved them further from listing definitions and closer to explaining design.

Wednesday

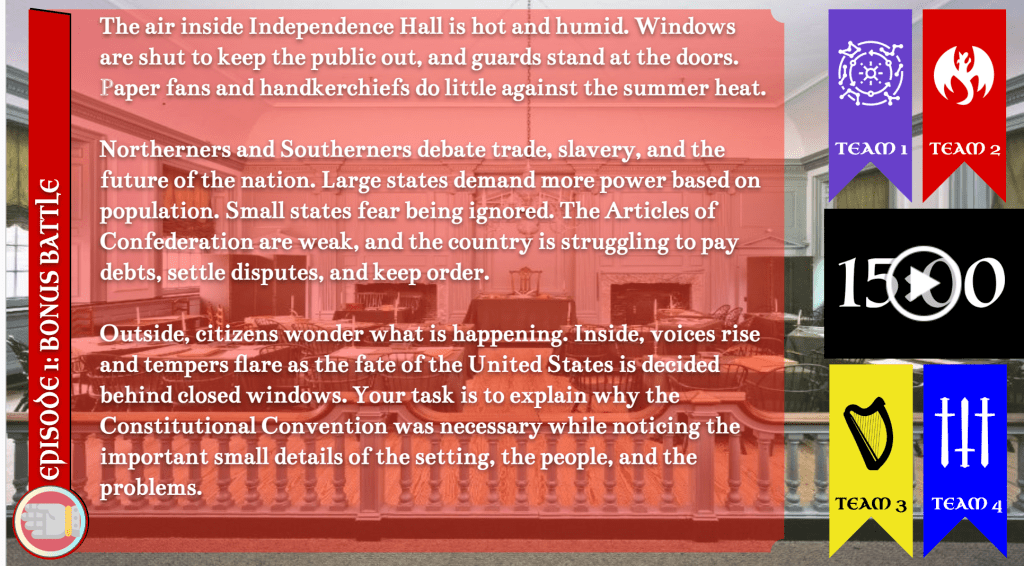

We launched our Early Republic unit with a new compelling question: How were the limits of the Constitution tested in the early days of the republic? I do not have much time and we are trying to catch up, so I decided to keep the focus tight. We are concentrating on key moments where the Constitution was pushed and tested, including Washington’s precedents, Hamilton’s Bank, the Whiskey Rebellion, the Alien and Sedition Acts, the Louisiana Purchase, and the War of 1812. The goal is not to add more content, but to examine how the system held up under pressure.

CyberSandwich: Framing the Tension

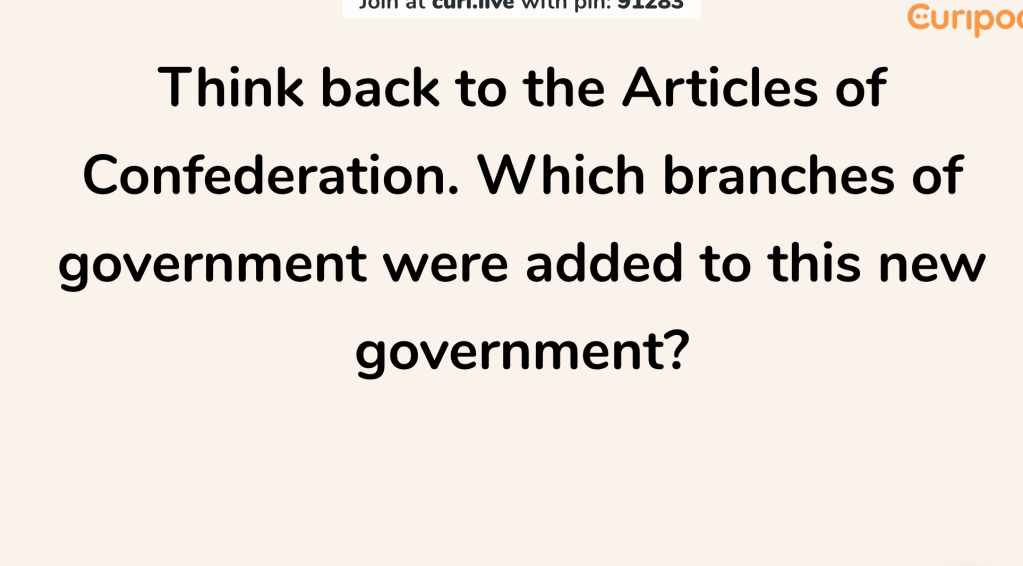

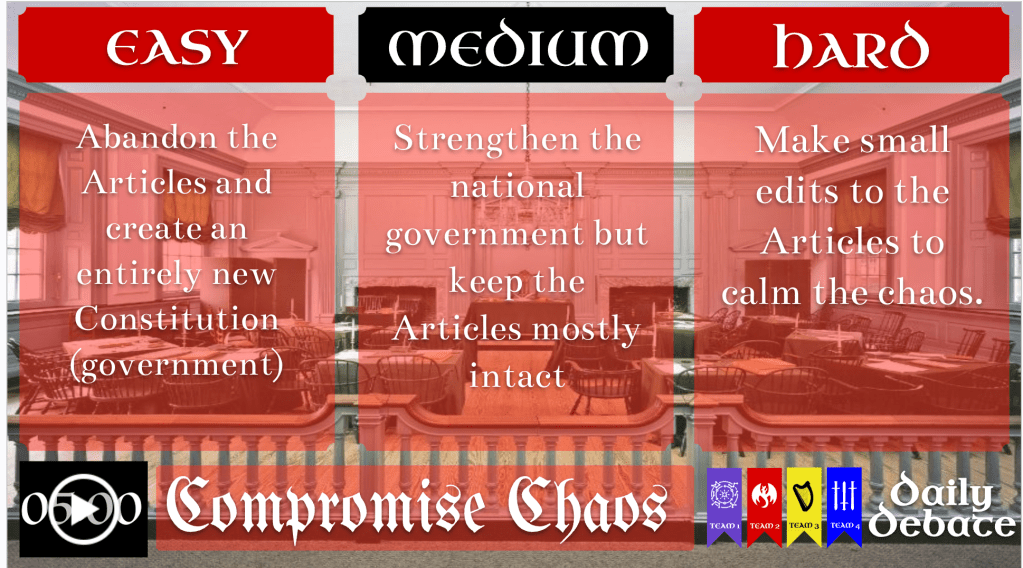

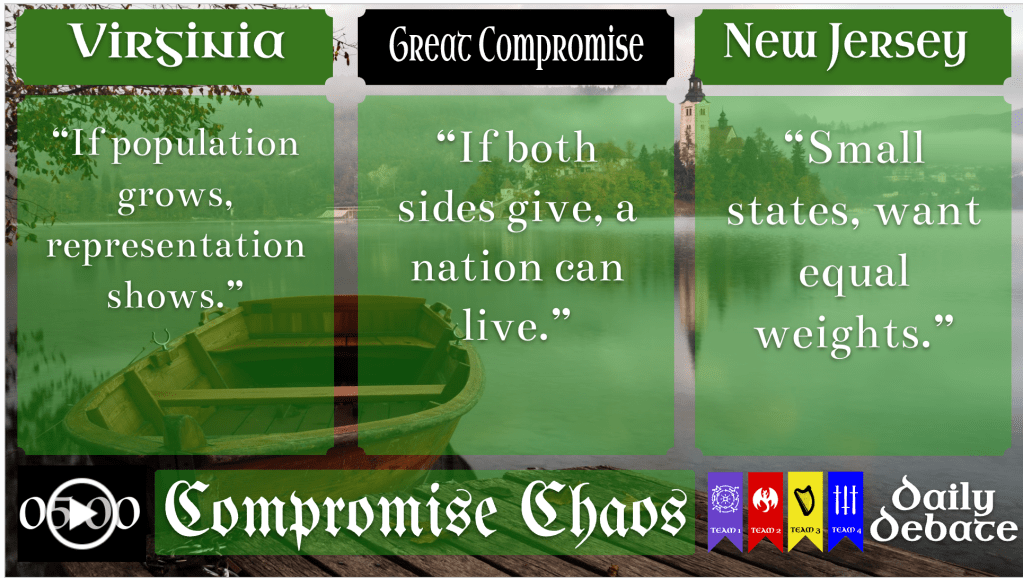

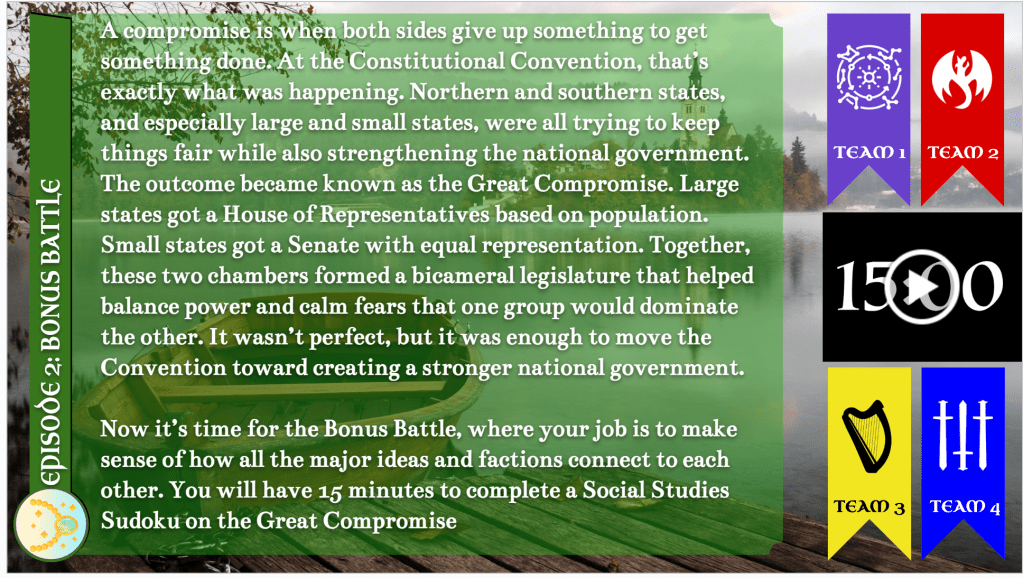

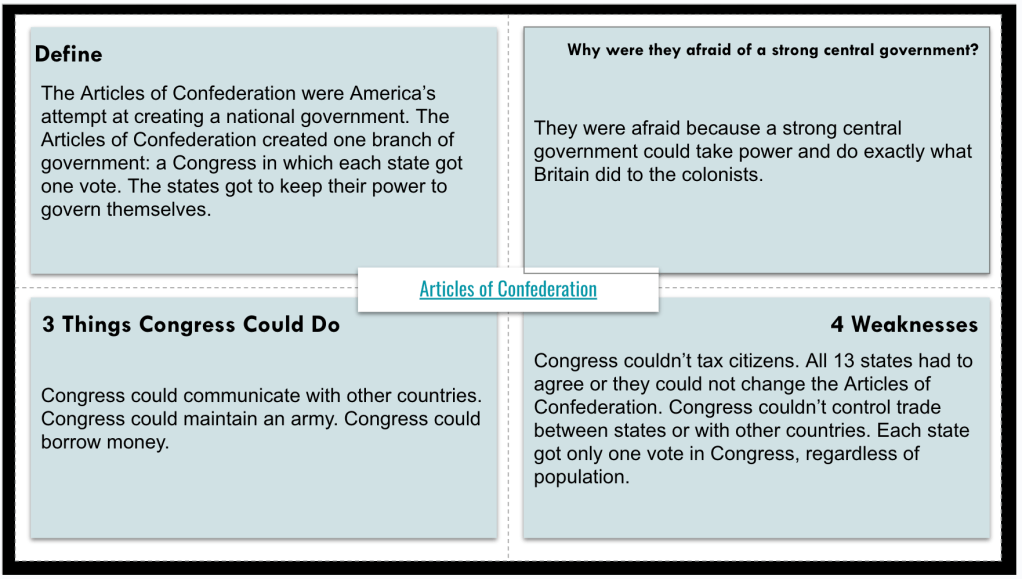

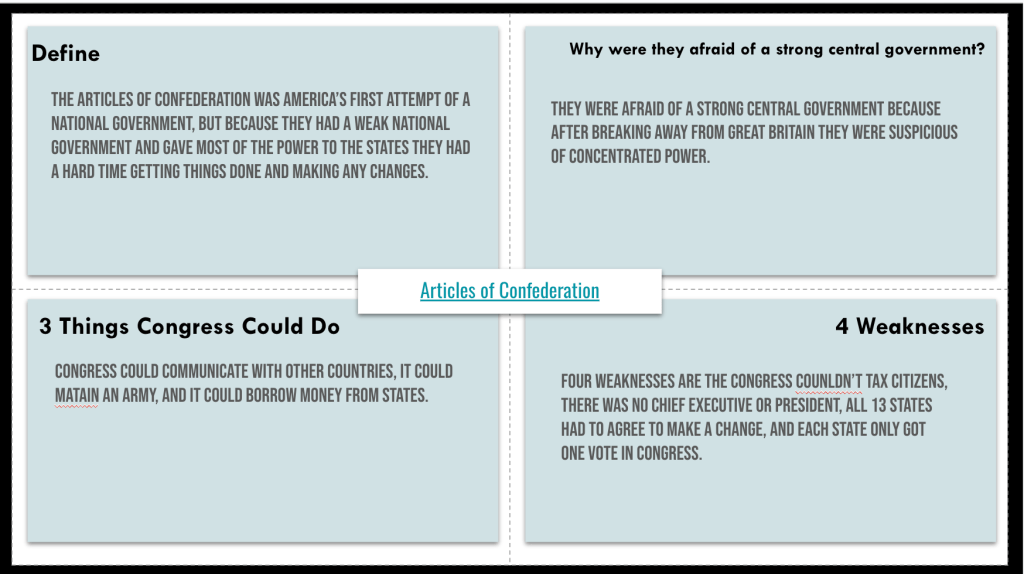

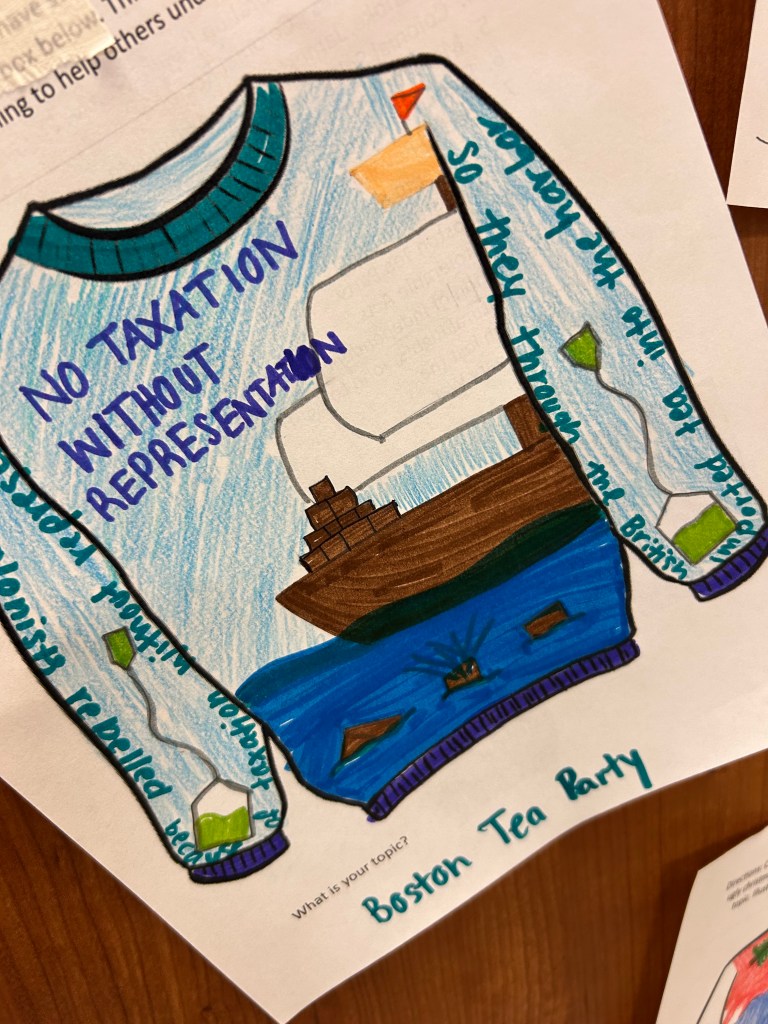

We began with a CyberSandwich built around one question: What major problems did America face from colonial times through its first government, and how did they fix them? Students worked with two different readings. One focused on rule under Britain and how the Constitution addressed abuses of power. The other focused on the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation and how the Constitution strengthened a government that had been too weak.

One government concentrated too much power. The other lacked enough power to function effectively. The Constitution attempted to strike a balance between the two. Students read independently, took notes, and then compared their notes with a partner. That comparison step forced them to clarify their thinking and tighten their understanding before moving on.

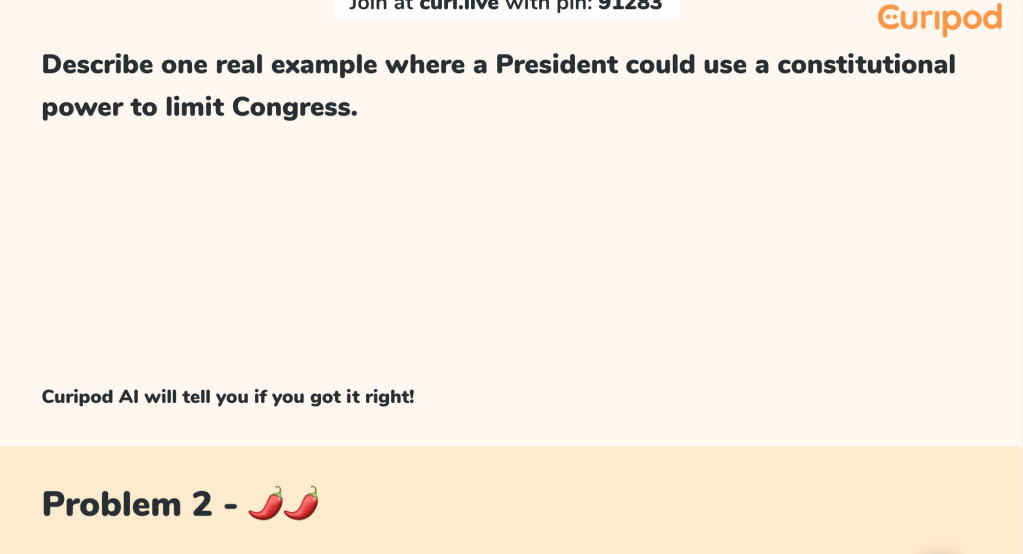

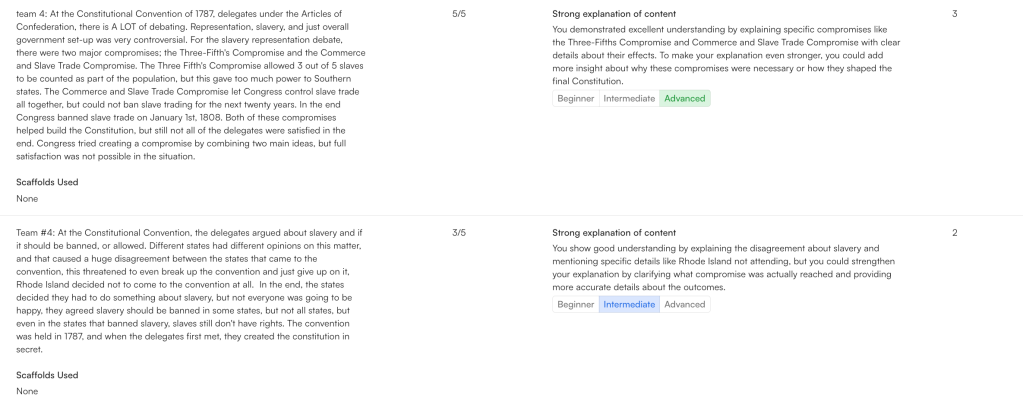

My Short Answer: Strongest Explanation Wins

After comparing notes, students used My Short Answer to write a summary responding to the question. The success criteria was clear. The strongest explanation of content would win. Not the longest paragraph. Not the most dramatic wording. The clearest explanation of the problems and how the Constitution addressed them.

We ended with a Battle Royale, and this time I joined in. I told them that if my paragraph made the top ten and they voted for mine, nobody would get candy. I intentionally wrote vague responses that sounded acceptable but lacked specific explanation. The room shifted immediately. Students reread more carefully. They debated which responses truly explained the content and which ones were too general.

They did not pick mine.

That told me they understood the difference between vague writing and strong historical explanation. By the end of class, students clearly saw the tension that shaped the Constitution. Britain represented concentrated power. The Articles represented weak central authority. The Constitution attempted to balance both. That framing sets up everything that follows as we examine how the limits of the Constitution were tested in the early republic.

Thursday

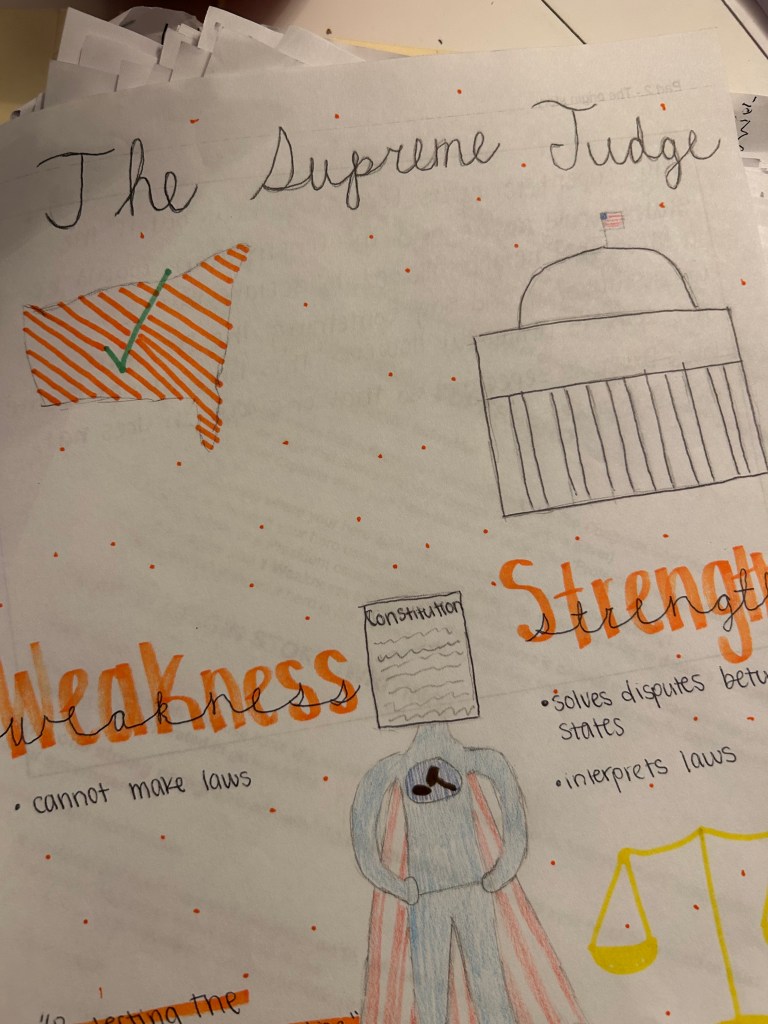

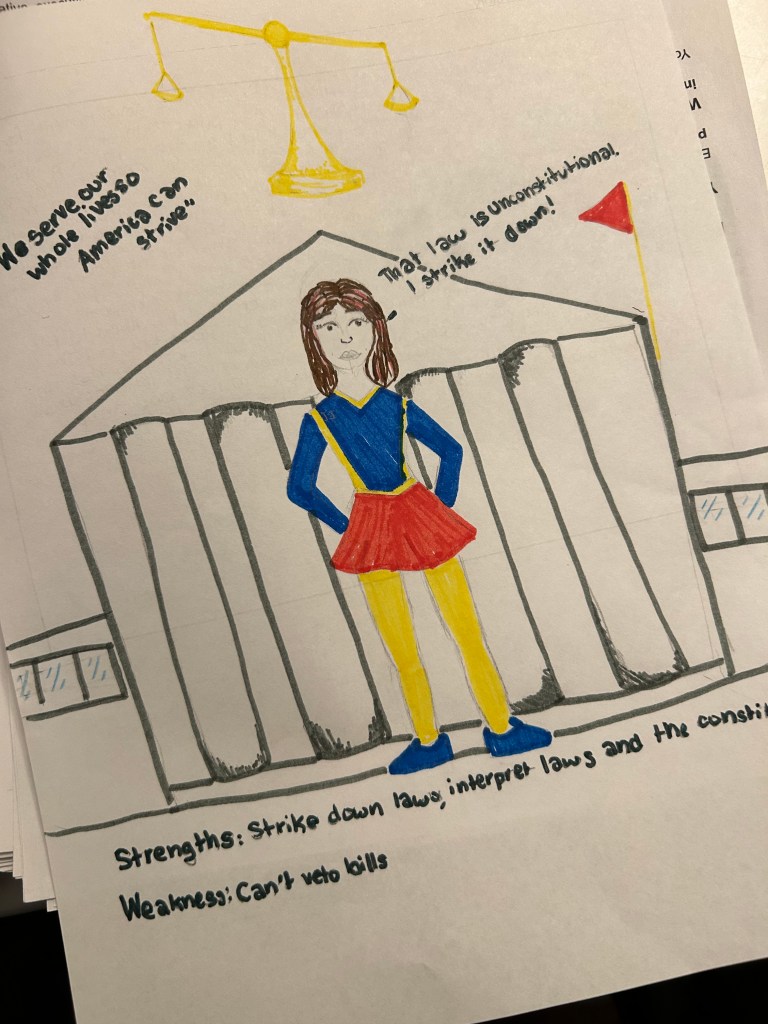

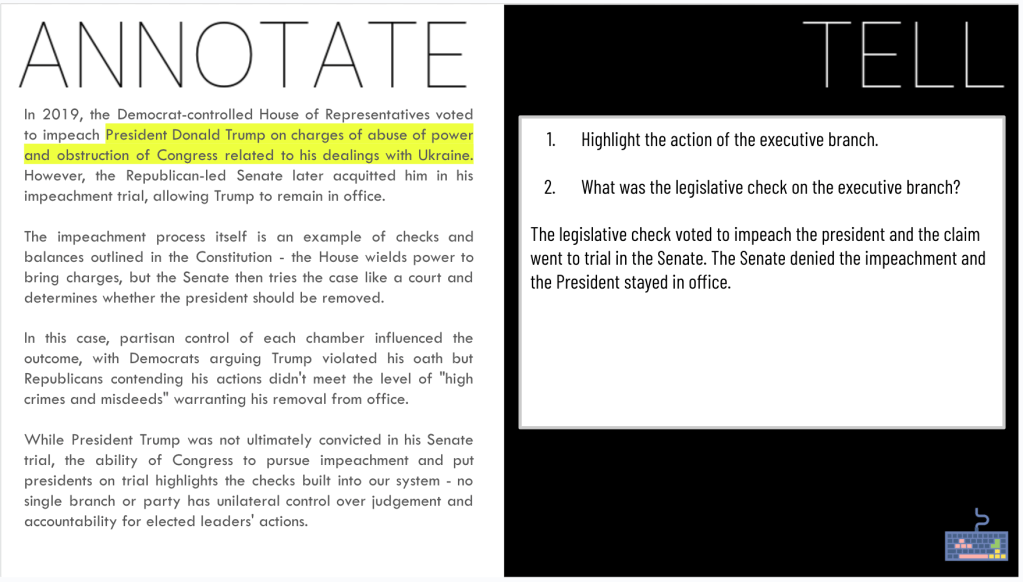

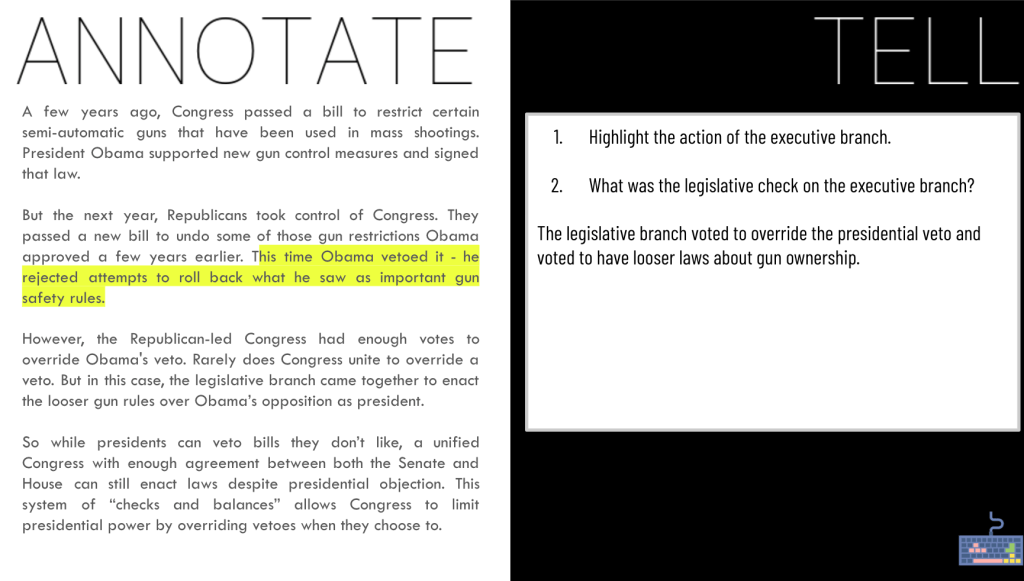

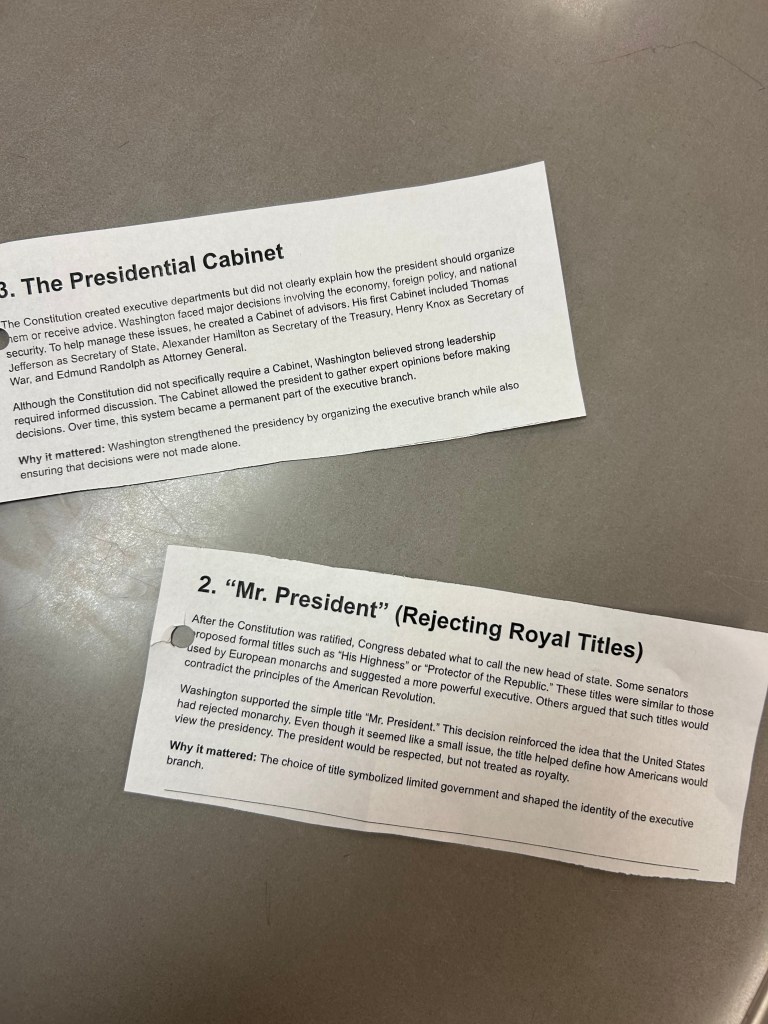

Sketch and Tell: Choosing a Precedent

Thursday was all about George Washington’s precedents. If Wednesday framed the tension of the Constitution being tested, Thursday showed how the very first president helped shape those limits in action.

We began with a Sketch and Tell. Students chose one precedent to focus on: the Cabinet, using the title Mr. President, the Farewell Address, the State of the Union, or the two-term tradition.

Students had to explain what the precedent was and why it mattered. Sketching forced them to simplify the idea. Explaining it out loud forced them to clarify its purpose. This was not about copying notes. It was about understanding why Washington’s choices mattered.

Frayer: Learning From Each Other

After students focused deeply on one precedent, I had them expand their understanding. Using a Frayer, they had to learn the four other precedents from classmates.

Instead of me reteaching everything, students became the content source. They moved, shared, clarified, and filled in the gaps. By the end of this segment, every student had exposure to all five precedents, not just the one they initially chose.

The structure stayed simple. Define it. Explain it. Why does it matter? Keep it tight.

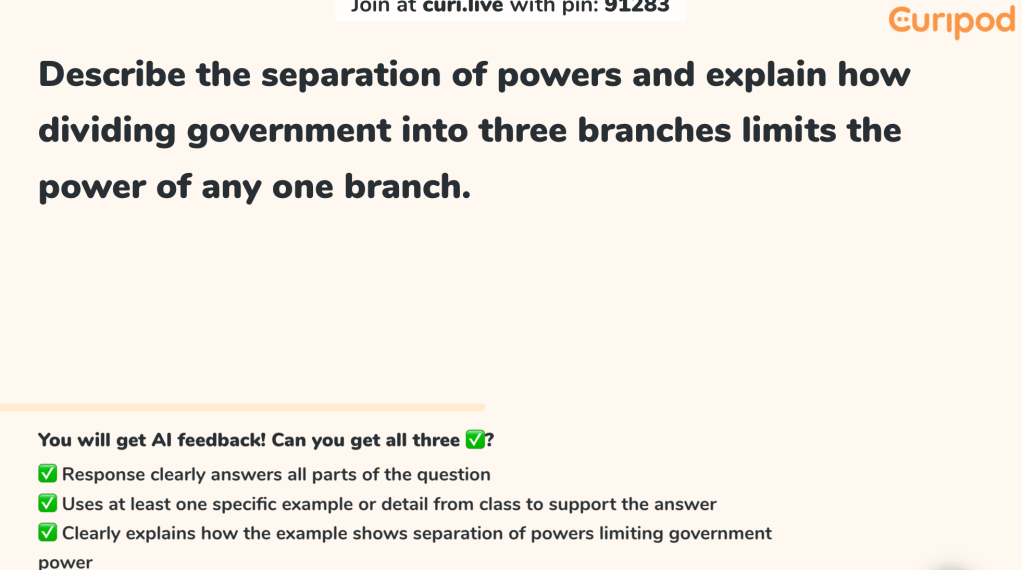

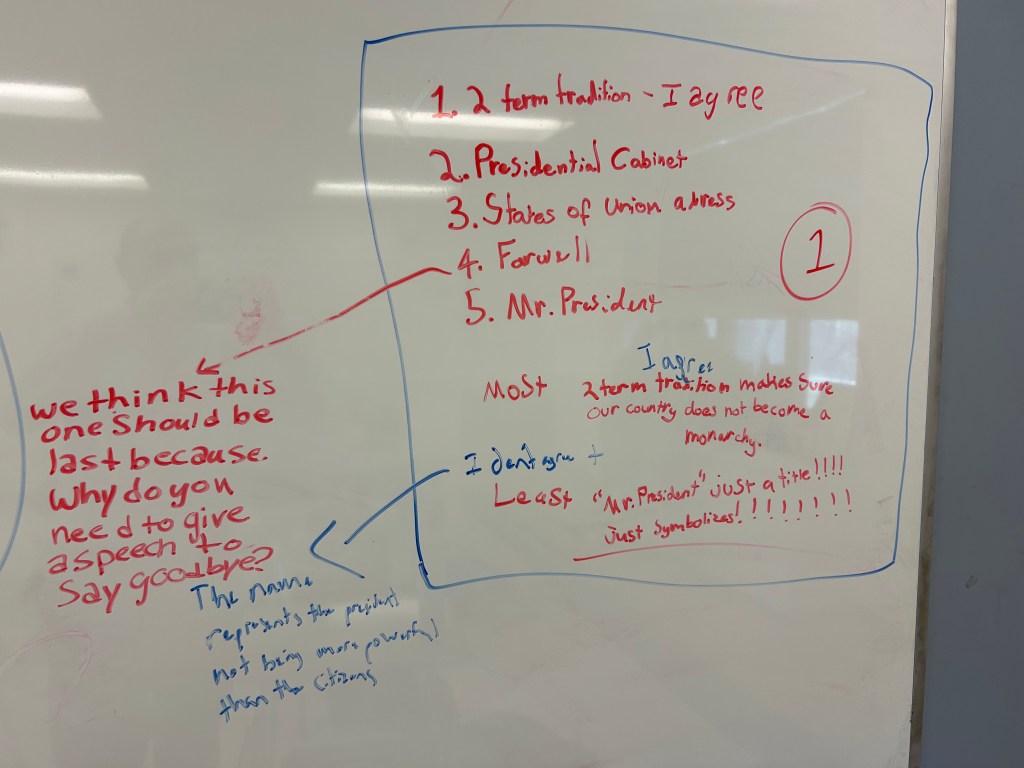

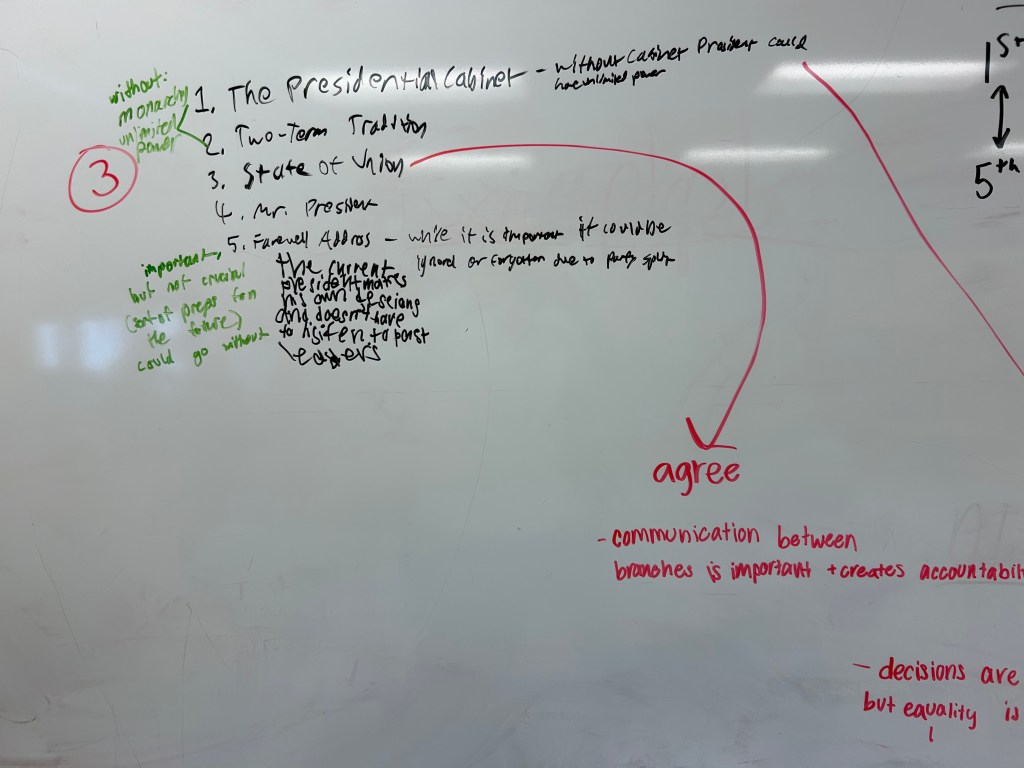

Building Thinking Classrooms: Ranking What Matters Most

Then we shifted into a Building Thinking Classrooms strategy. Students were randomly grouped and given a whiteboard. Their task was to rank the five precedents from most important to least important.

But ranking was not enough. They had to justify the top and the bottom choice.

This is where the thinking deepened. Is the two-term tradition most important because it prevents monarchy? Is the Cabinet more important because it shapes executive decision-making? Is the Farewell Address critical because it warned against political parties?

There was no obvious answer. That is the point.

Circulate, Disagree, Add

After groups created their rankings, students rotated to a new board. Their job was to find something they disagreed with and add to it. They had to explain why they would adjust the ranking or challenge the reasoning.

This part was powerful. Students were not defending their own ideas anymore. They were evaluating someone else’s thinking. It forced them to reread, reconsider, and refine their arguments.

The boards became layered with reasoning instead of just lists.

Flip the Precedent

We finished with a final push. Students chose one precedent and flipped it.

What if Washington had served for life?

What if he never created a Cabinet?

What if he refused to give a Farewell Address?

What if he demanded a royal title instead of Mr. President?

Students predicted two consequences and then decided whether the presidency would become stronger or weaker.

This question forced them to see that precedents are not small decisions. They shape the balance of power. Serving two terms instead of life sets a tone. Calling himself Mr. President instead of something grand keeps the office grounded. Creating a Cabinet structures executive power.

Flipping the decision revealed the stakes.

By the end of class, students were not just memorizing Washington’s precedents. They were analyzing how early decisions tested the limits of executive power and shaped the presidency.

Friday

EdPuzzle and Archetypes

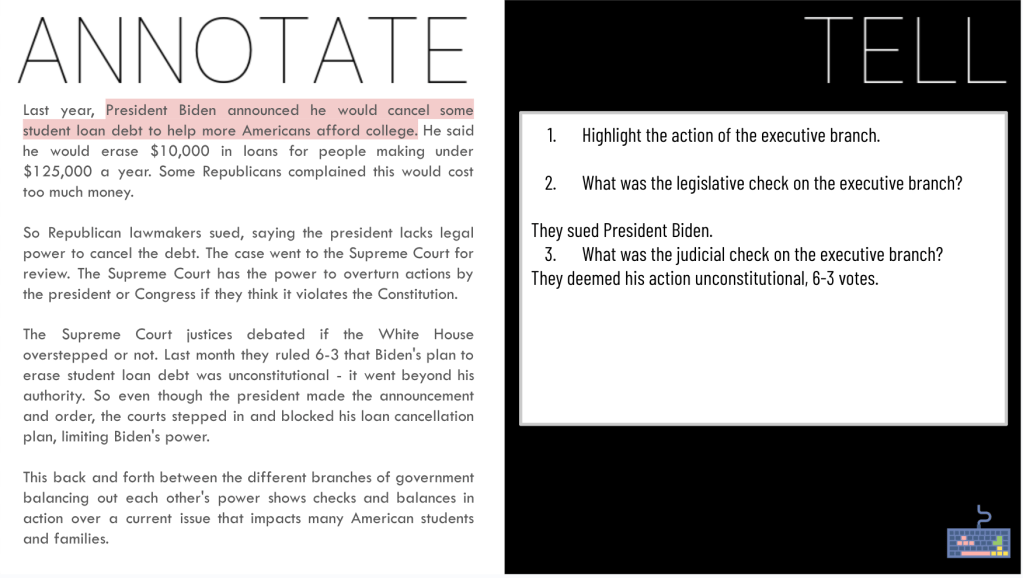

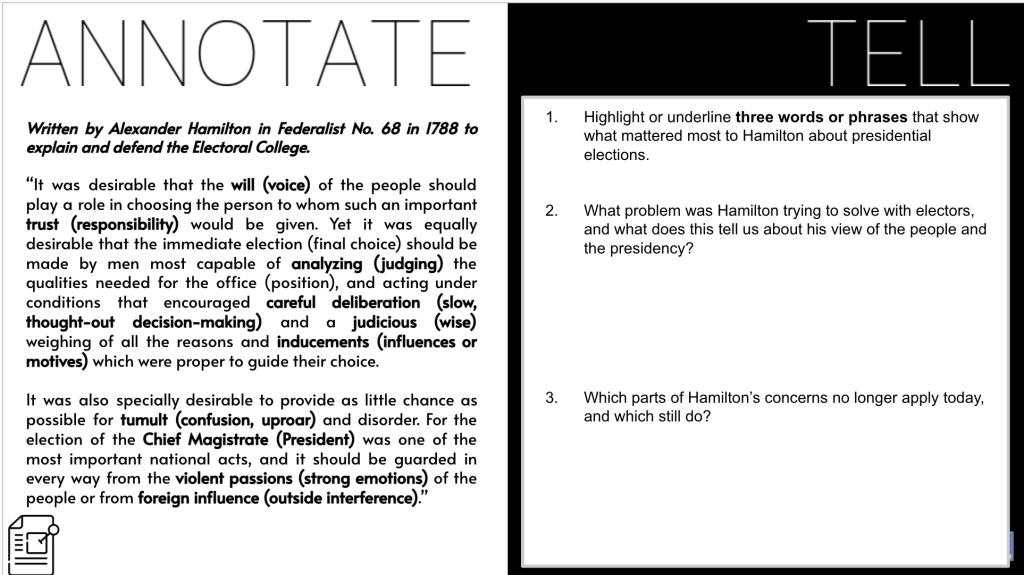

Friday’s goal was clear. Students needed to understand how Alexander Hamilton tested the limits of the Constitution through his financial plan, specifically the creation of the national bank.

We began with an EdPuzzle video on Hamilton. I chose this particular video because it emphasized something students often miss. Hamilton was not just thinking about debt. He was thinking about the future of American manufacturing. His financial plan and support for the national bank were tied to a larger vision of economic growth and national strength.

I paired the video with an Archetype Four Square. Students had to identify Hamilton’s archetype and justify it using evidence from the video. Many identified him as a Creator or a Magician. The Creator fit because he was designing an entirely new financial system. The Magician surfaced because he saw possibilities others did not and tried to transform the country’s economic future.

The key requirement was evidence. Students could not just label him. They had to point to moments in the video that showed his vision, his ambition, and his willingness to push boundaries.

Slowing Down for the Story

When we moved deeper into Hamilton’s financial plan, I did something I rarely do. I lectured.

There are moments in middle school history where structure matters more than movement. Hamilton’s plan has too many moving pieces for students to independently untangle all at once. Tariffs. Excise taxes. The national bank. Consolidating state debts. Loose versus strict construction. Hamilton urging Congress to pass these policies. It is a lot.

I have been around long enough to know that if students do not see the full picture clearly, they will lose the thread. So I gave them the framework. I explained how the pieces connected and why each one mattered.

Cabinet Battle #1

To anchor it, I told them, “Today I’m going to give you the history and meaning behind the lyrics to Cabinet Battle #1 from Hamilton.”

That resonated immediately.

Now the debate was not abstract. It was the argument between Hamilton and Jefferson. Should the Constitution be interpreted loosely or strictly? Does the Constitution allow a national bank even if it does not explicitly say so? Does the Necessary and Proper Clause stretch that far?

Framing the lesson through the musical helped students connect to the conflict. They could see that this was not just about money. It was about how far executive and federal power could extend under the Constitution.

In this class, that is all we had time for. But it was enough.

Students left understanding that Hamilton was not simply building a bank. He was testing the boundaries of constitutional interpretation. And in doing so, he helped define how flexible the Constitution could be.

Lessons for the Week

Monday – Limited Government Rack and Stack

Tuesday – Check out Snorkl

Wednesday – CyberSandwich

Thursday – Washington’s Precedents variation rack and stack

Friday – Hamilton Rack and Stack