This week in Room 234 was packed with a mix of EduProtocols, hands-on activities, and a focus on understanding colonial tensions. From Sketch and Tell-O for visualizing British taxes on Monday to analyzing historic protests with 8 Parts and Cyber Sandwich later in the week, each day brought something new. We tackled the Boston Tea Party with Number Mania to dig into key details and wrapped up with an inquiry lesson on “having a voice in government.” I even worked in guided notes—a rare move for me—to support their understanding of the British Acts. Each protocol helped keep the energy high while pushing students to think critically about the events leading up to the American Revolution.

Monday

Monday didn’t start out the way I’d planned. I wasn’t feeling well, but I managed to make it to school—until that weird feeling just took over and I had to head home. I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I ended up leaving…guided notes. 😳 Yep, the thing I swear I’m anti- guided notes. But sometimes, you’ve got to roll with what works for the kids you have this year, even if it’s not your ideal plan.

Guided Notes

I’m working with a student population that’s still getting used to taking ownership of their learning. So, while guided notes aren’t my go-to strategy (and honestly, something I’d like to phase out), they’re a starting point. I figured that leaving the notes would help the students review what we’ve already learned about British acts and taxes while introducing some new information like the Townshend Acts, Tea Act, and Intolerable Acts. I could’ve covered all the British acts and taxes at once, but knowing the group I have this year, I wanted to avoid overload. Small doses, steady progress—that’s the plan.

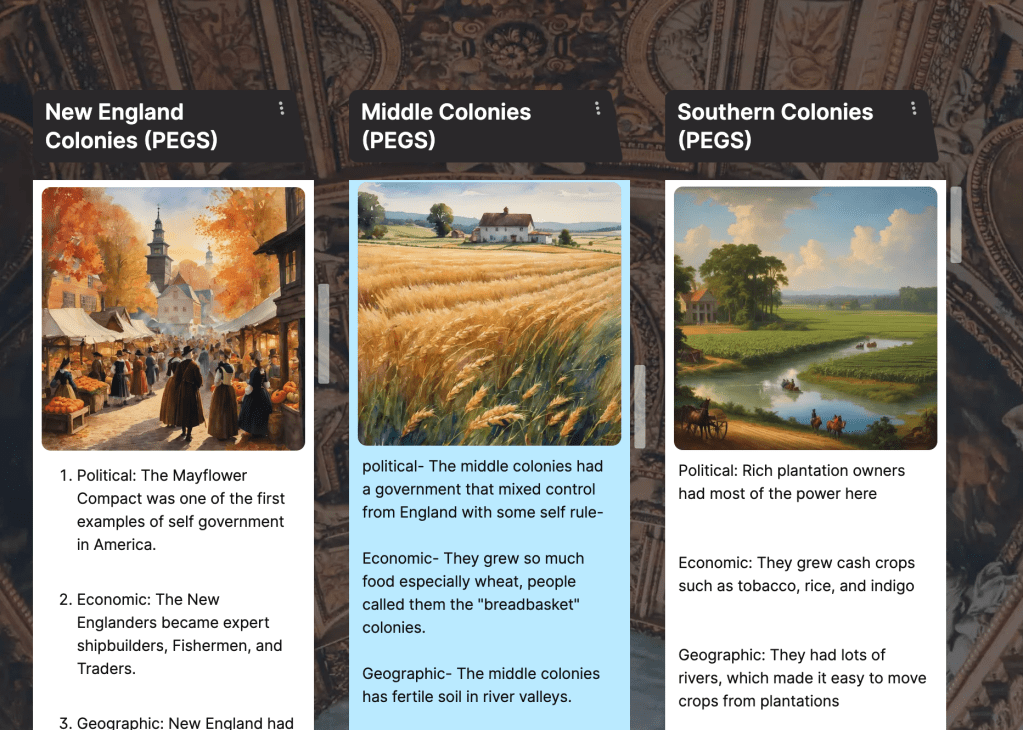

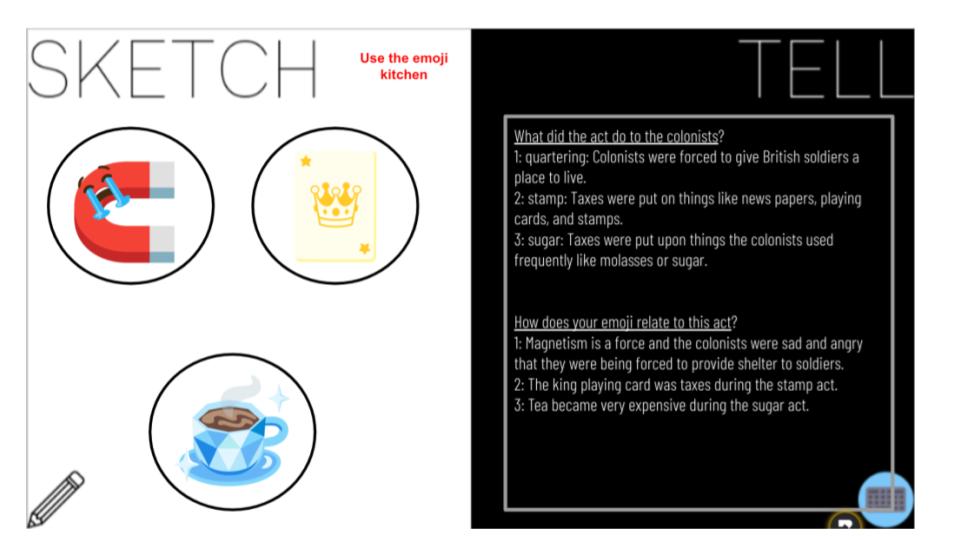

Sketch and Tell-o: Emoji Kitchen Edition

To follow up the guided notes, I left a Sketch and Tell-o activity. I had the students use the Emoji Kitchen to create visual representations of the British acts. The goal was for them to combine two emojis into one new emoji that represented each act, like using a tea cup and an angry face to illustrate the Tea Act. It’s a fun and creative way to get them thinking beyond the text, and I was hoping it would engage their imaginations a bit more than traditional worksheets.

Gimkit

I set up a Gimkit as an assignment and left it for them to complete. It was meant to reinforce the acts we covered, testing their recall and giving them that competitive, game-based edge they enjoy. I figured it was the perfect way to end the lesson independently—keeping it interactive even while I was out.

The Results: Progress, but We’ve Got Work to Do

Here’s what happened:

- About 80% of students completed the guided notes, which isn’t bad considering it’s what they’re used to.

- 50% made it through the Sketch and Tell-o, which shows me they’re still warming up to that format.

- Only 30% completed the Gimkit—but of that 30%, the overall average score was 82%, so they’re retaining the info, which is a positive takeaway.

Not the most productive day, but it’s progress. The plan is to ease them out of guided notes and into more interactive and student-led learning activities as the year goes on. We’re building stamina and confidence, one small step at a time. This class is growing—slowly but surely—and I’m adapting my approach to meet them where they’re at while pushing them forward. It’s all part of the journey.

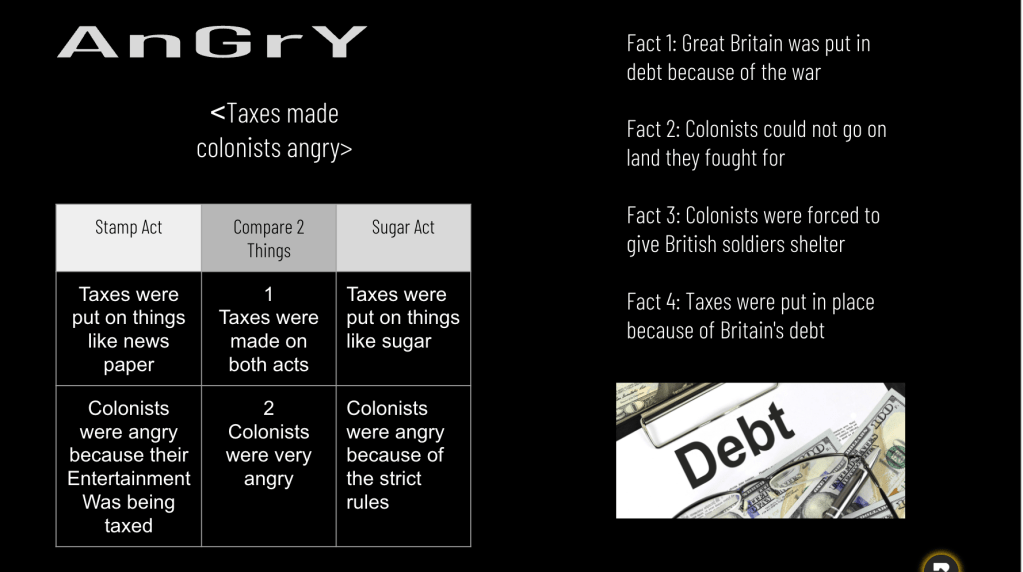

Tuesday

Tuesday, I was back in action and ready to keep building on the momentum (even after a rough Monday). To really drive home the idea of British acts and taxes, I used a classic Mr. Roughton lesson called “Of Parents and Children.” It’s a gem that uses a humorous, relatable approach to connect the build-up of the American Revolutionary War with the students’ own experiences.

“Of Parents and Children”: Bringing the Revolution Home

In this lesson, the premise is simple but effective—compare historical events to everyday situations that students can relate to. I read scenarios that mimicked the British acts and taxes but presented them as if they were happening between parents and children. For example, one scenario had the “parents” making their child pay the family Netflix bill (which, of course, got a lot of groans and eye rolls). The students wrote down how they would feel if that happened to them—most of the responses ranged from “unfair” to “totally unreasonable.”

After each scenario, we flipped the script and connected it to the actual historical event, like the Stamp Act or Townshend Acts. The students then made connections between the two, understanding how colonists might have felt and why they were so angry. It’s always great to see the lightbulbs go off when they realize how similar these feelings of unfairness are to the colonists’ experiences.

Taking Longer Than Expected

The activity ended up taking longer than I anticipated—students were really into it, and we had some great discussions about fairness and control. We didn’t have time for all the follow-up activities I had planned, but the engagement and dialogue made it worth it. It was one of those moments when slowing down felt right, even if it meant changing the pace of the day.

Fast and Curious Wrap-Up

To wrap things up, we did a quick Gimkit Fast and Curious. It was a great way to reinforce what we’d discussed in a fun and interactive format. The class averages ranged from 90% to 76%, showing that even with a more hands-on, discussion-based approach, they were retaining the key information.

It was a solid day of learning that tied the content to something personal and familiar for the students, making the history feel less distant and more relevant. Onward to the next lesson! 💥🔥

Wednesday

Wednesday, I could tell the energy in the room was running low after all the talk about British acts and taxes. It was time to pivot and move on. I decided to shift the focus to how the colonists protested these taxes and why they chose to take action. And, to really hook them, I wanted to start with something dramatic—violence.

Kicking Off with a Hook: “The Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man”

To grab their attention right off the bat, I used the famous cartoon, The Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man. This picture tells a pretty wild story—perfect for keeping 8th graders interested while diving into the deeper meaning of protest and rebellion. I knew the image’s intensity would catch their eye and drive home the point that sometimes people resort to violence when they feel unheard.

I started the lesson with a quote on the board:

“He picked off his charred skin, kept it in a box, and showed it to King George III to prove his loyalty.”

It was just the hook I needed. Eyes went wide, and hands shot up. The curiosity was sparked, and we were off to a solid start. This lesson was done entirely on paper because I’ve noticed that my students engage more with physical materials than with digital ones—so we’re rolling with what works.

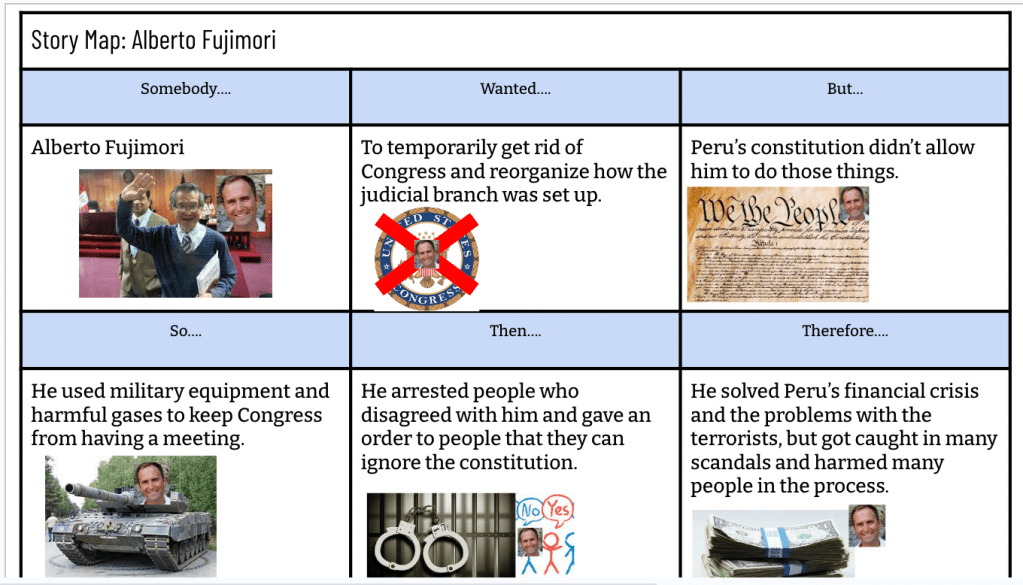

8Parts: Analyzing the Cartoon

We kicked off with an 8Parts activity. The goal? Analyze the cartoon with no background information—just raw observation. I asked them to list nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs they saw. This helped them start thinking critically without immediately jumping to conclusions. After they’d had some time to work through their observations, I filled them in on the historical context behind the cartoon and had them consider: Why would someone create this?

To wrap up the 8Parts, they crafted a summary using all the parts they had identified. It was cool to see them start piecing together how protest could turn violent and why.

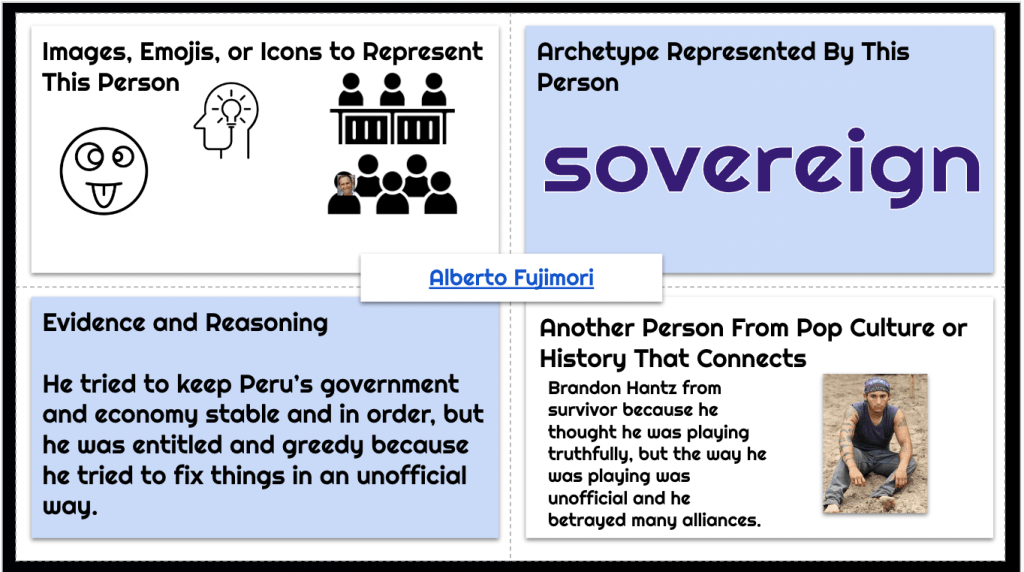

Frayer Models: Sons of Liberty & First Continental Congress

Next up, we switched gears and worked on two Frayer Models—one for the Sons of Liberty and one for the First Continental Congress. I provided the Google definition for each term, but I wanted them to make it their own. They had to create their own definitions, jot down two examples of people they might have heard of who were part of each group, and sketch a picture to represent each one. It was a solid way to build context and give them some hands-on work that helped reinforce the key players in these protests.

CyberSandwich: The Story of John Malcolm

For the main event, we dove into a CyberSandwich about the cartoon The Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man. The story focused on John Malcolm, who was tarred and feathered by the Sons of Liberty. This narrative always grabs attention—it’s intense and dramatic, exactly the kind of thing that gets 8th graders engaged. They took notes using the who, what, when, where, why structure. They were all in, and you could see the gears turning as they made connections between the story and the broader context of colonial protests.

To wrap up the CyberSandwich, I tried something different. I had AI create a really bad summary paragraph for the students to fix. They nailed it—picking it apart, rephrasing, and turning it into something meaningful. It was awesome to see them take ownership of their corrections and really focus on improving the content.

The last task was to write a caption for the cartoon, but from the perspective of a British loyalist. This was a challenge for them. They struggled to switch perspectives, and it was clear that empathy mapping is still something we need to work on. But it’s all part of the process, and I’m confident that with more practice, they’ll get there.

Reflection

Wednesday was an active day that pushed the students to connect personally with history while developing key skills like analysis, summarization, and empathy. The energy in the room was definitely better, and I felt like the shift in focus was just what we needed to keep the momentum going. On to the next! 💥🔥

Thursday

Thursday was all about continuing the theme of protest, shifting from violent and intimidation protests to destructive protests when people felt their voices weren’t being heard. Our focus? The Boston Tea Party—a classic example of colonists taking drastic measures to make their point.

Intro to Number Mania

I love using Number Mania for events like the Boston Tea Party, but I realized I hadn’t introduced this activity to my students yet. So, before diving into the history, I set up a practice round to get them comfortable with the concept.

To start, I had each student create a slide with 3 numbers that were significant to them. It could be anything—like their birthday, favorite sports jersey number, or the number of pets they have. Then, I taught them how to use Word Art, change colors and fonts, and add drop shadows to make everything pop on their slides. This creation time took about 12-15 minutes, but it was worth it. They got into the groove of designing and making their numbers stand out.

This step was crucial; it got them familiar with the process and built confidence so when we moved into the actual content, they’d feel ready.

The Real Deal: Boston Tea Party By the Numbers

With the practice under their belts, it was time for the real Number Mania experience. I had Claude (AI) create a “Boston Tea Party By The Numbers” reading. Of course, I fact-checked everything before handing it over to the students—got to keep things accurate!

To set the stage, I gave them a quote:

“The Boston Tea Party was a massive and well-organized protest that required careful planning, involved many people, and had huge consequences.”

Their goal? Find 4 numbers and facts in the text that supported this quote. We read the text together, and they highlighted the numbers that stood out. Then, they created a slide with their findings, just like we practiced.

Success with Number Mania

Thanks to the practice run, they nailed it. I was hearing a lot of “This is easy!” as they worked, which is exactly what I want—confidence and engagement. They connected the numbers back to the larger idea of the Boston Tea Party being a well-planned protest, and it was great to see them make those connections independently.

This approach worked wonders. It wasn’t just about understanding the history; it was about reinforcing the process, building confidence, and making it feel achievable. We’re definitely keeping Number Mania in the rotation!

Onward to the next chapter in our revolutionary journey! 💥🔥

Friday

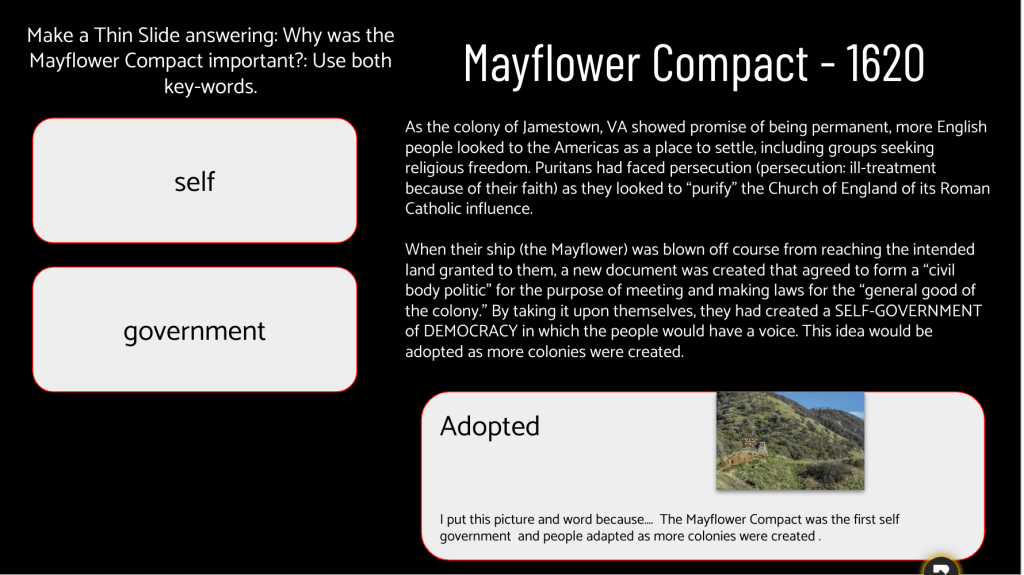

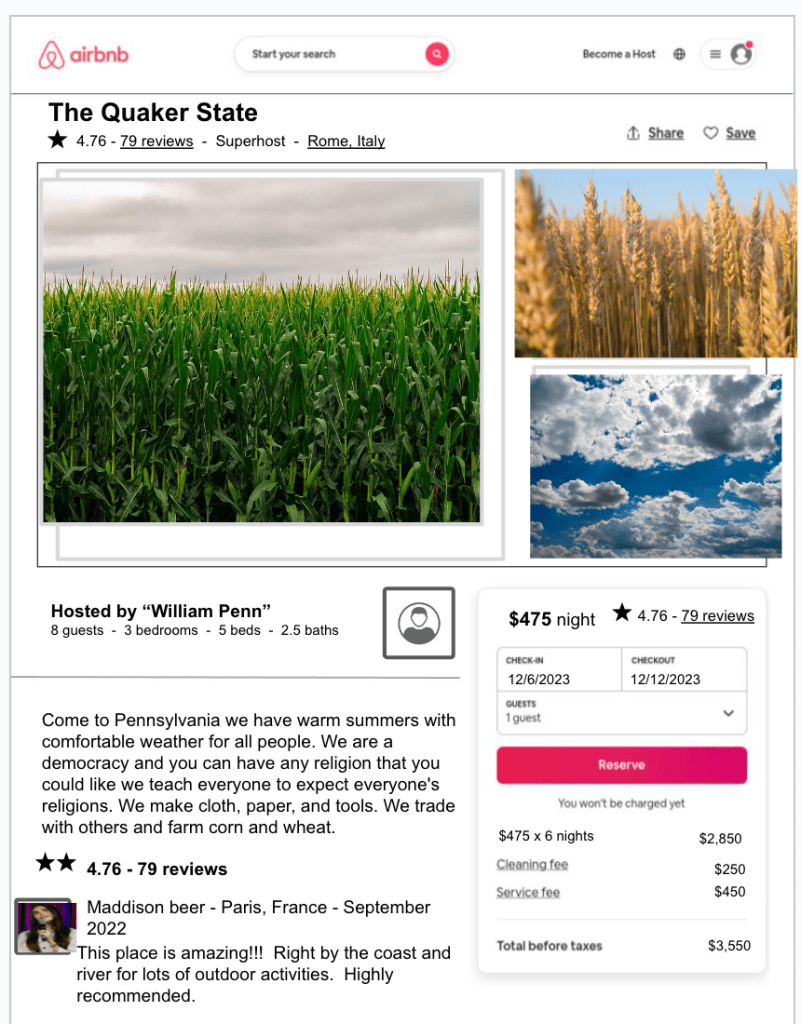

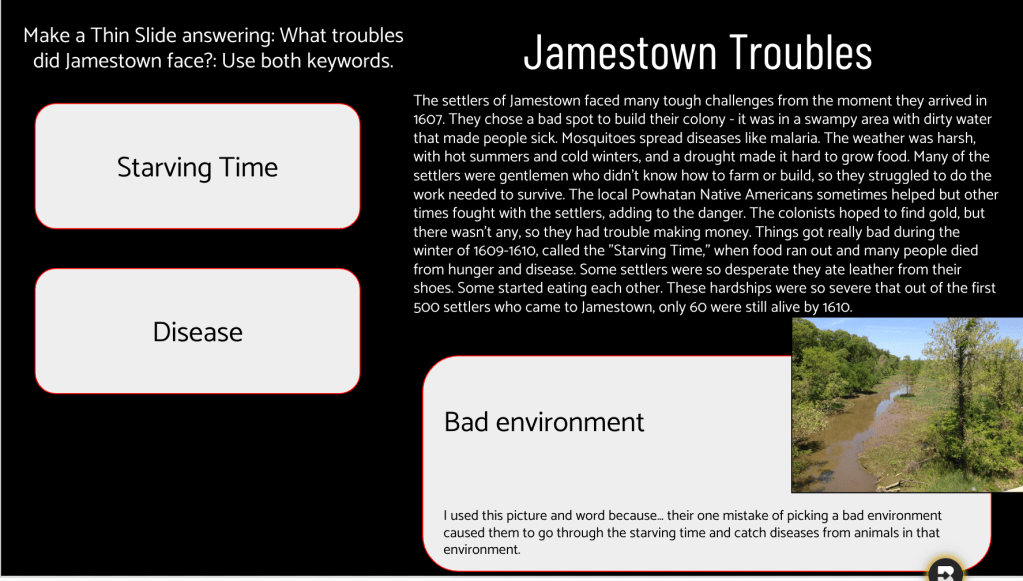

Primary Sources Lesson Link, Thick Slide Summary

Friday was a day off for me, so I set up an inquiry lesson for my students—a deep dive into the question, “Why is it important to have a voice in government?” This inquiry question felt like the perfect way to wrap up everything we’d covered throughout the week about colonial protests, representation, and rebellion.

Tackling Inquiry with a Little Help from AI

Now, I actually like some of the inquiry lessons from the textbook, but the problem is they’re often a bit much. These lessons can be overly complicated, and many of the primary sources aren’t exactly written at an 8th-grade-friendly level. Sure, I want students to stretch their thinking and be challenged, but there’s a fine line. Most students don’t have the stamina for hours of “critical thinking” with material that feels too complex or abstract.

So, I decided to give this inquiry lesson a boost to make it more accessible. Here’s what I did:

- Streamlining the Primary Sources: The lesson had five primary sources, so I took screenshots and ran each one through Claude AI. I asked it to rewrite the sources at a 7th-grade reading level, but still maintain the original tone and style. This way, the students could understand the essence without getting bogged down by archaic language.

- Adding Context & Guiding Questions: For each source, I had the AI add context to set the stage—who wrote it, why, and how it fits into our big question. I also had it extract any guiding questions from the textbook and even create one additional question for each source to push the students’ thinking just a bit further.

- Final Synthesis Question: The ultimate goal was for students to answer the question, “Why is it important to have a voice in government?” After they’d worked through the sources and guiding questions, they were meant to summarize their findings on a Thick Slide.

The Real-Life Results

Did most students finish the work on paper? Honestly, I’m not sure. I saw that about 30 out of 90 students got to the Thick Slide summary. My guess is that the majority were working through the sources at their own pace, which is totally fine. The focus was less on “getting to the end” and more on engaging with each source meaningfully.

This setup was a bit of an experiment, but I’d say it was worth it. Having simplified sources and targeted questions helped make the inquiry more manageable. Even if they didn’t all finish, I’m hopeful that they took away some understanding of why representation matters—a key theme we’ll keep building on as we move forward in our revolutionary timeline.