I’m discovering as the year moves along that life at the Villa comes with a steady stream of interruptions to the normal school rhythm. Practice high school placement tests, walk-a-thons, shadow visits, pep rallies, and more. Honestly, it feels like way more than I ever experienced in public schools. But here’s the thing, it’s all good. These moments create a climate and culture that is unlike any place I’ve been, and I’m learning to embrace them as part of what makes this community special.

At the same time, I’m not getting as much done in class as I would like. This is a process and these kids are not used to my style or the tech usage I bring. Eventually, I want to get back to where I was getting three to five protocols accomplished in a class period.

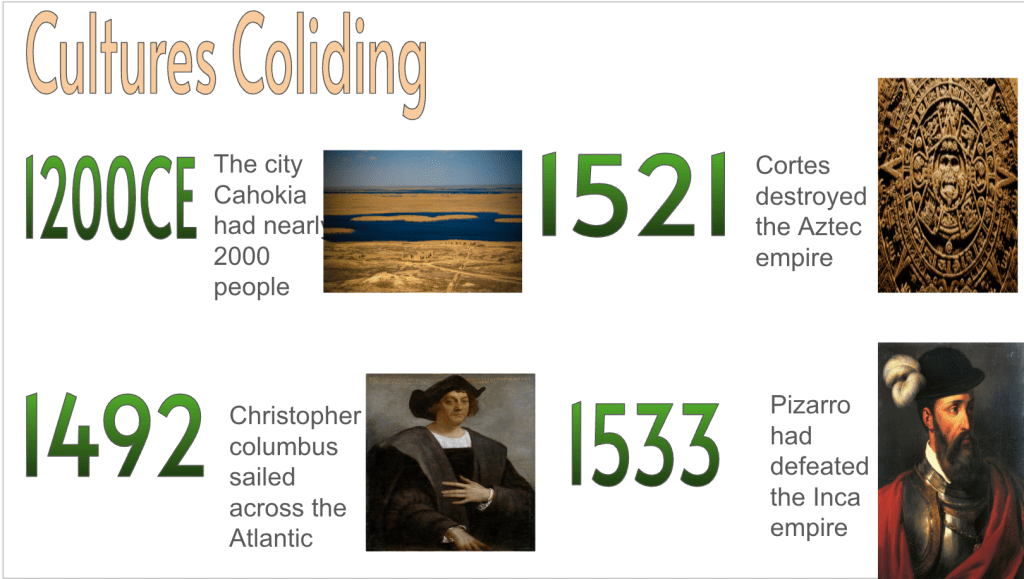

Even with the curveballs, we kicked off Unit 2 on exploration and colonization this week. We started with a Number Mania preview to frame the big picture, then dug into how Native Americans arrived, adapted, survived, and thrived. We took a pause to step into a one-day lesson on 9/11, and then the week closed with two days of unusual schedules that didn’t leave much time for momentum.

Monday – Unit Preview Number Mania

Tuesday/Wednesday – Regions Organizer, 6 Word Story

Thursday/Friday – 9/11 Retro Report

Monday

We started the week by previewing Unit 2 and setting the tone with a Fast and Curious. I introduced our guiding question for the unit: How did European colonization and exploration impact Native peoples and North America? Scores on the quiz ranged from 60 to 74 percent, which gave us a good baseline for where we’re starting.

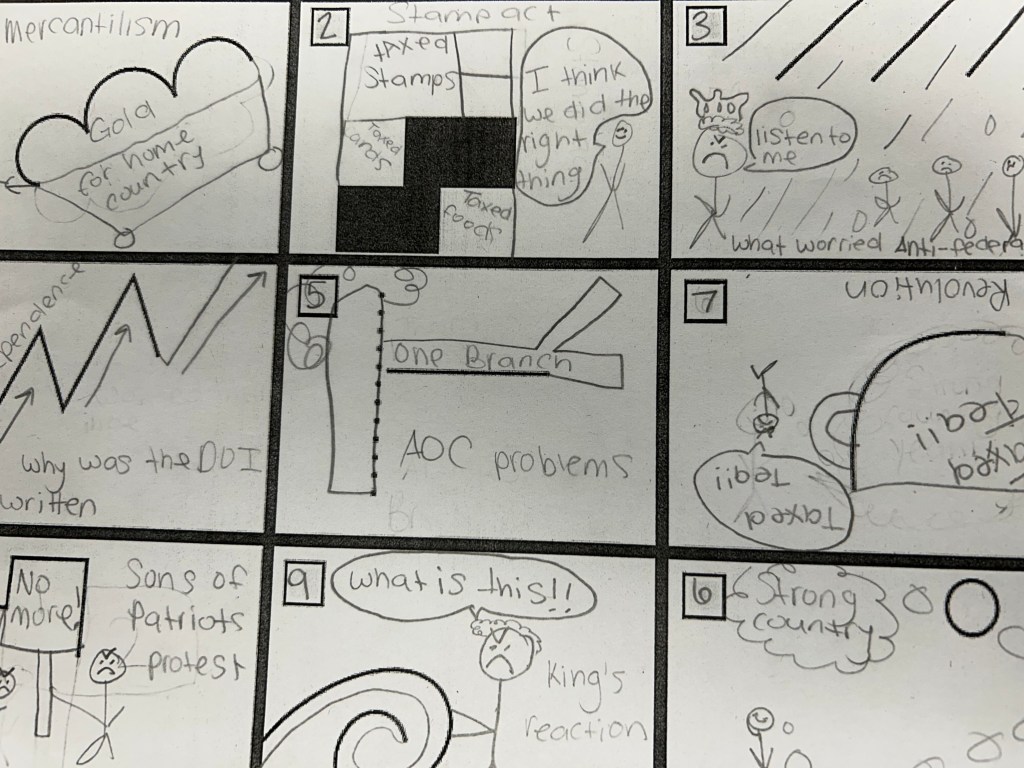

From there, I passed out a one-page reading that matches the flow and structure of the unit. It began with Beringia, moved through Native peoples growing, adapting, and thriving, and then shifted to the arrival of Europeans and the impact that followed. We paired this reading with a Number Mania. I have found that opening units with a Number Mania gives students a ton of data points to help frame the big picture in space and time. For this one, students had to find four numbers that proved Europeans impacted and disrupted Native life.

Something that stood out was how students reacted to this activity compared to Friday. When we first did a low-cognitive, smart start Number Mania, many of them rolled their eyes and wondered why we were doing it. Some even thought it was cheesy. I get it. These kids have been together since preschool, and with grade levels of only 30 to 40 students, they know each other well. Icebreakers feel strange. But today was different. Several admitted that the smart start practice actually made today’s Number Mania super easy. It was a small win.

Tuesday and Wednesday

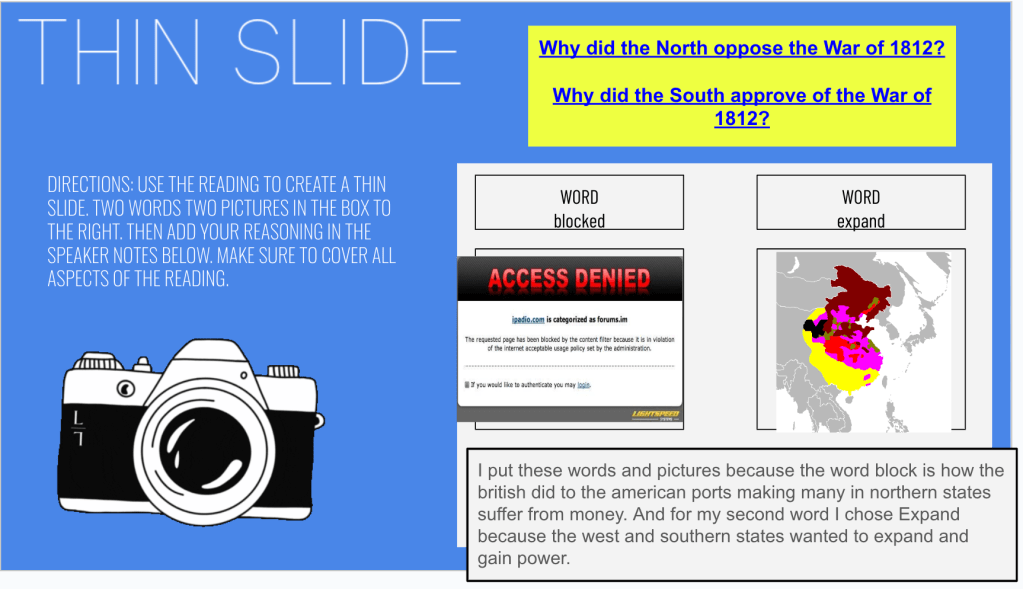

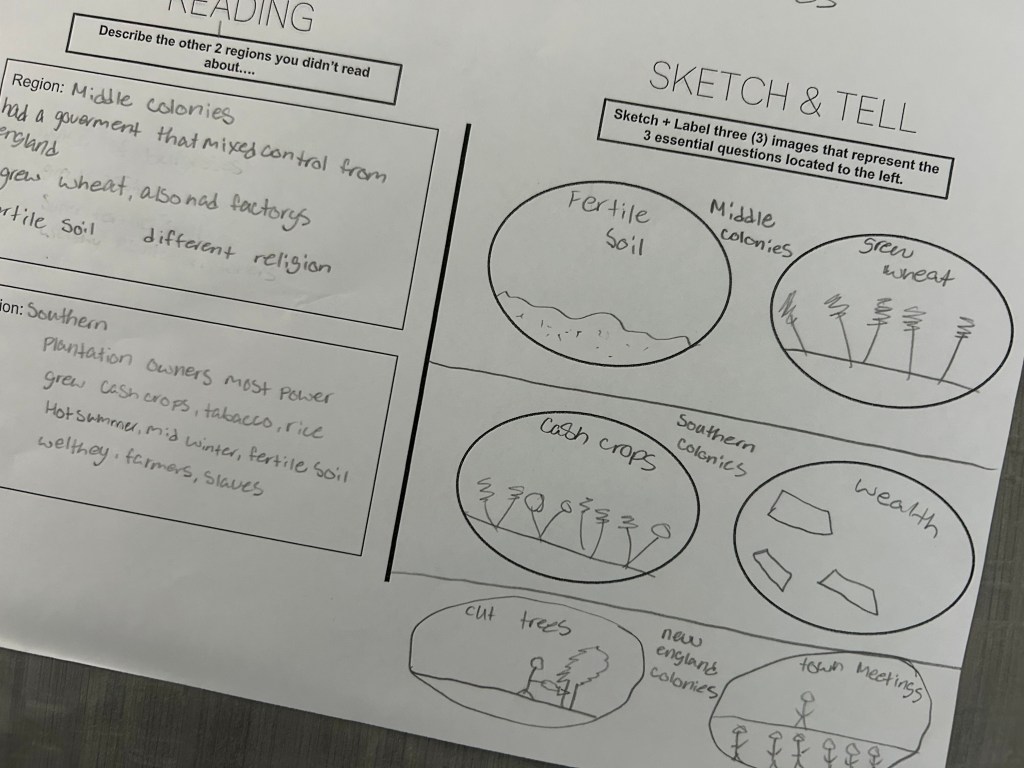

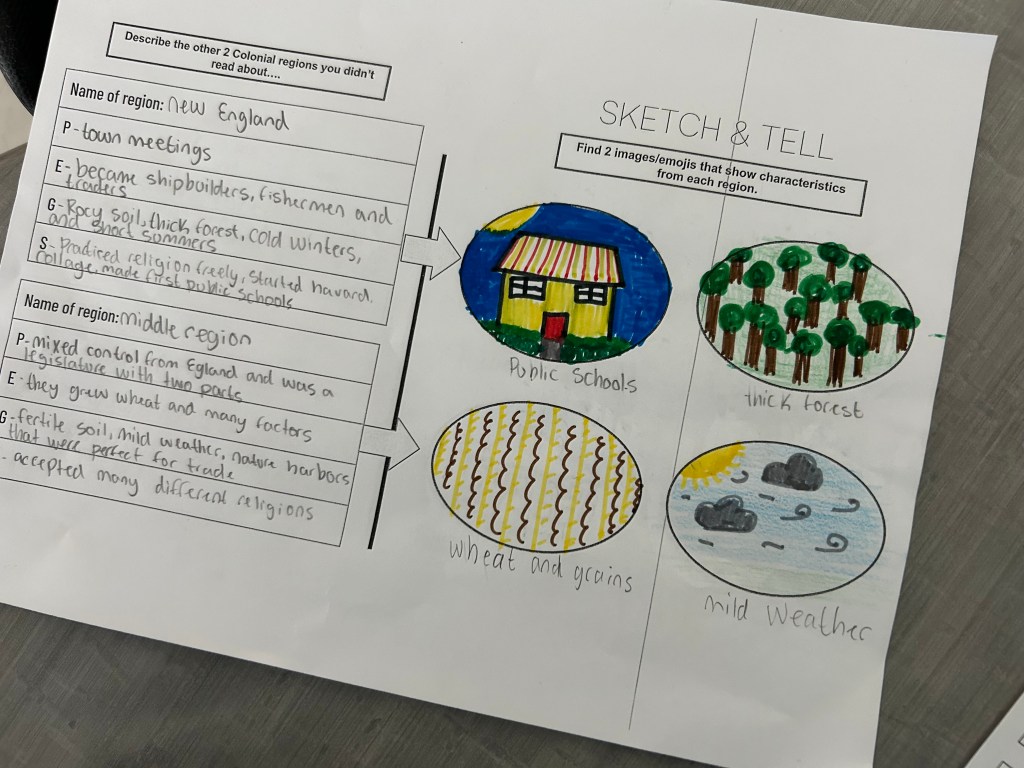

We spent two days on a lesson that simplified what the textbook made overwhelming. The text mentioned around 14 Native tribes, which is too much to meaningfully process, so I narrowed it down to five regions: Eastern Woodlands, Mesoamerica, Southwest, Northwest, and Plains. The goal was for students to understand how Native peoples adapted, survived, and thrived within their regions based on geography

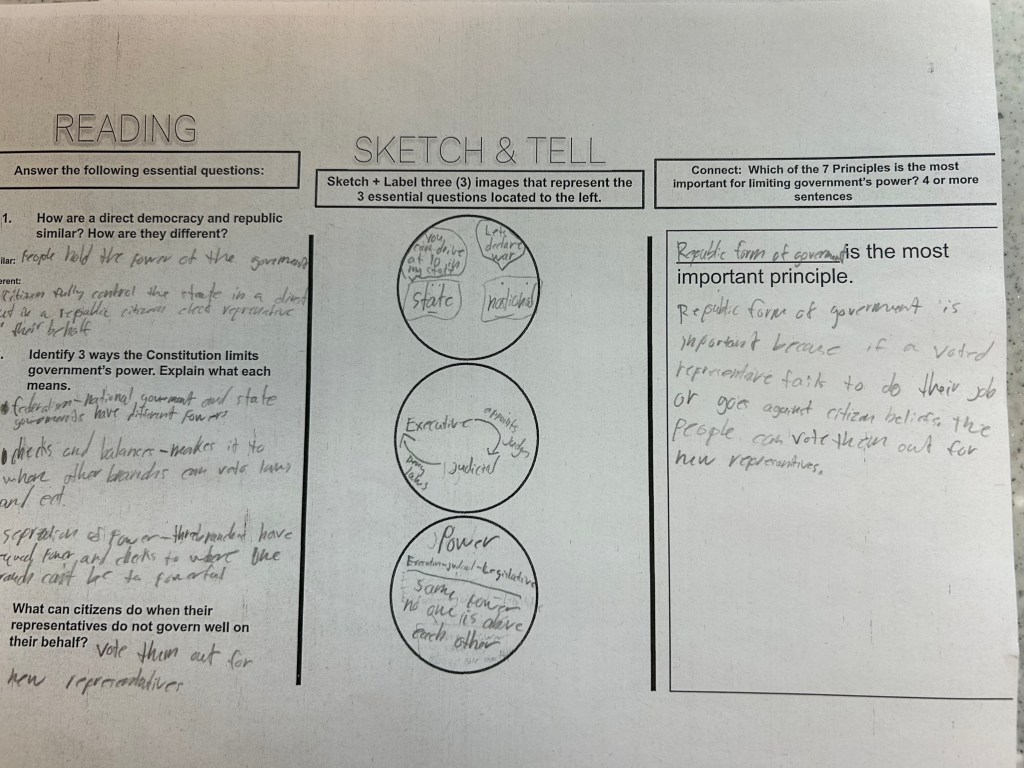

I structured the lesson to move from DOK 1 to DOK 2 to DOK 3. Many of these students are used to recall and rote memorization, but I want to push their critical and creative thinking. We started with stations where students read about the different regions and tribes, then categorized information into location, religion, environment, food, and housing. As they worked, I explained the learning process. I told them that transferring information from a reading to an organizer is DOK 1.

The next step was choosing three of the five regions and comparing them with a triple Venn diagram. At first, many students filled the middle space with answers like “they were in North America.” I kept coming back with the question, “If I asked you how they adapted and survived, would saying they were all in North America answer that question?” That pushed them to think deeper, and many went back and improved their comparisons.

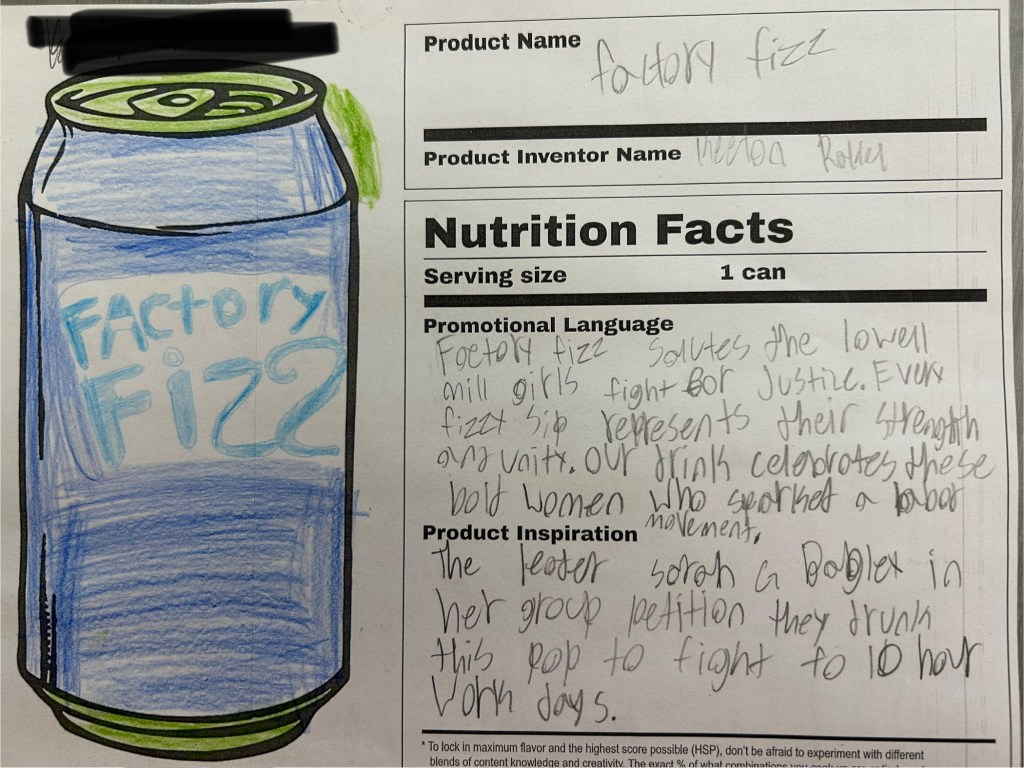

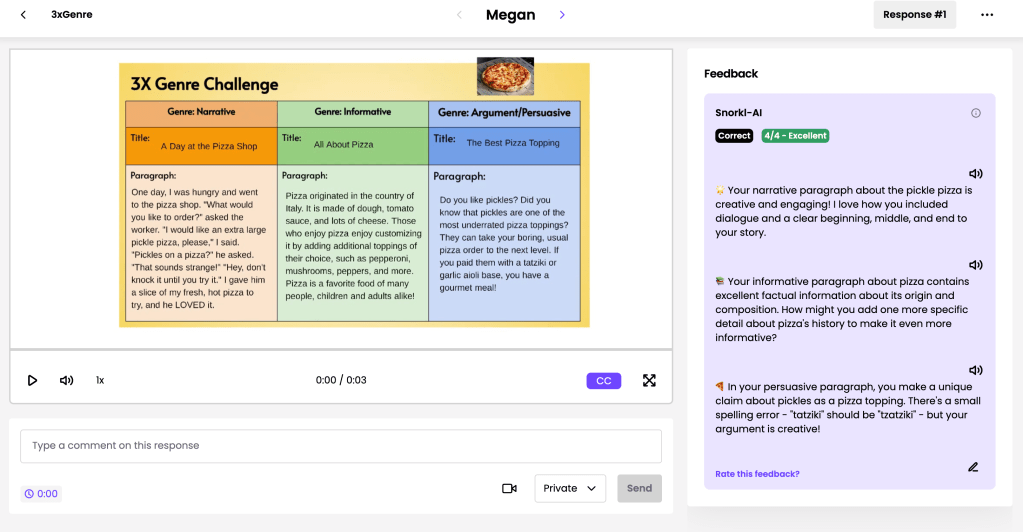

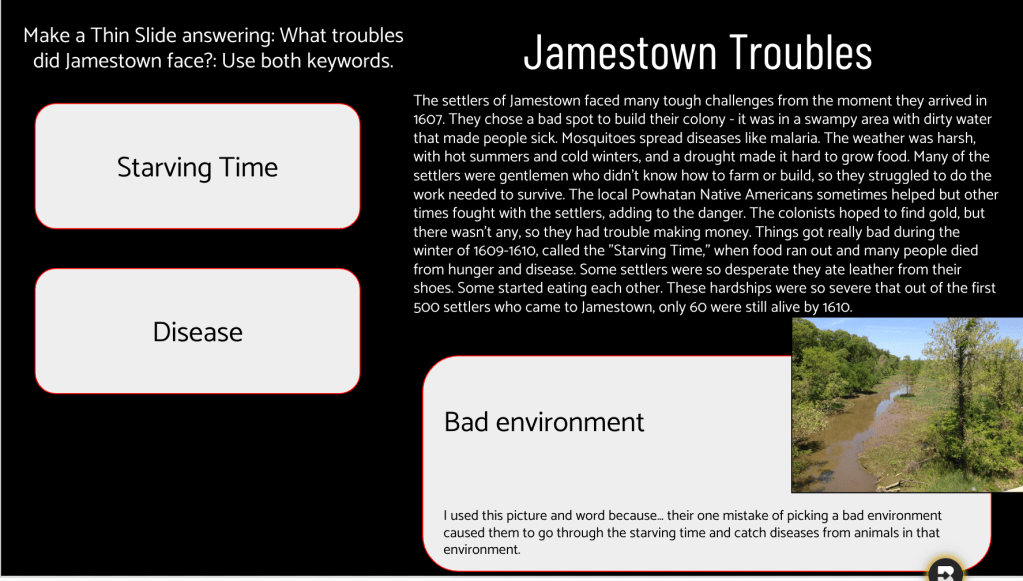

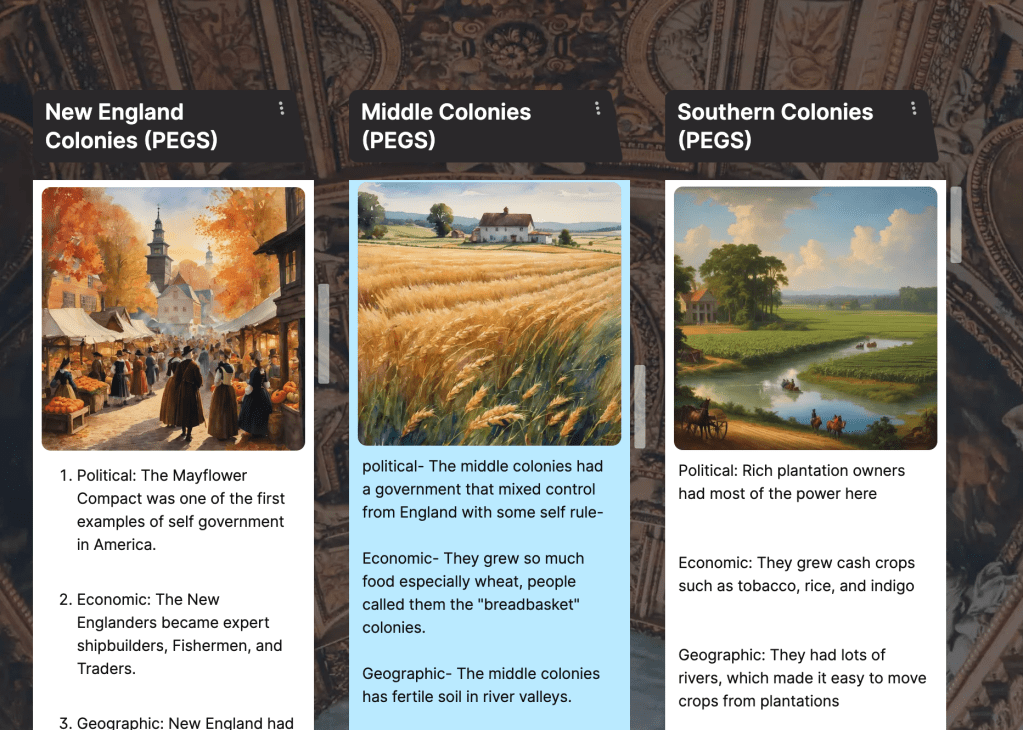

For the last part, I used a strategy from EMC2Learning and had students write three six word memoirs about the three regions from their Venn diagram. The focus was on adaptation and survival. I explained that comparing information with a Venn diagram is DOK 2, while writing six word memoirs that capture the essence and most important information is DOK 3. I chose this activity because it is creative, simple, and gave them practice on Google Slides again. Students added text boxes, pictures, and changed word art, while also working part of the lesson on paper for balance and familiarity.

We wrapped up both days with a Fast and Curious, which raised class averages into the 80 to 94 percent range. That growth showed them that practice and persistence are paying off.

Thursday and Friday

Thursday

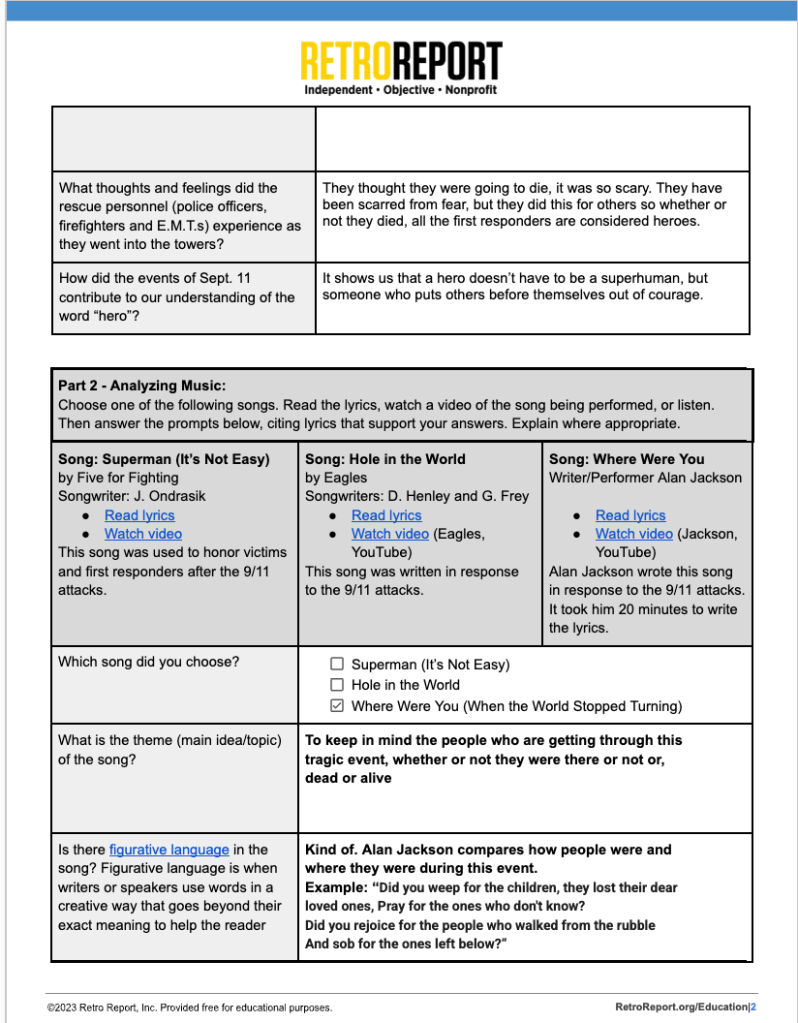

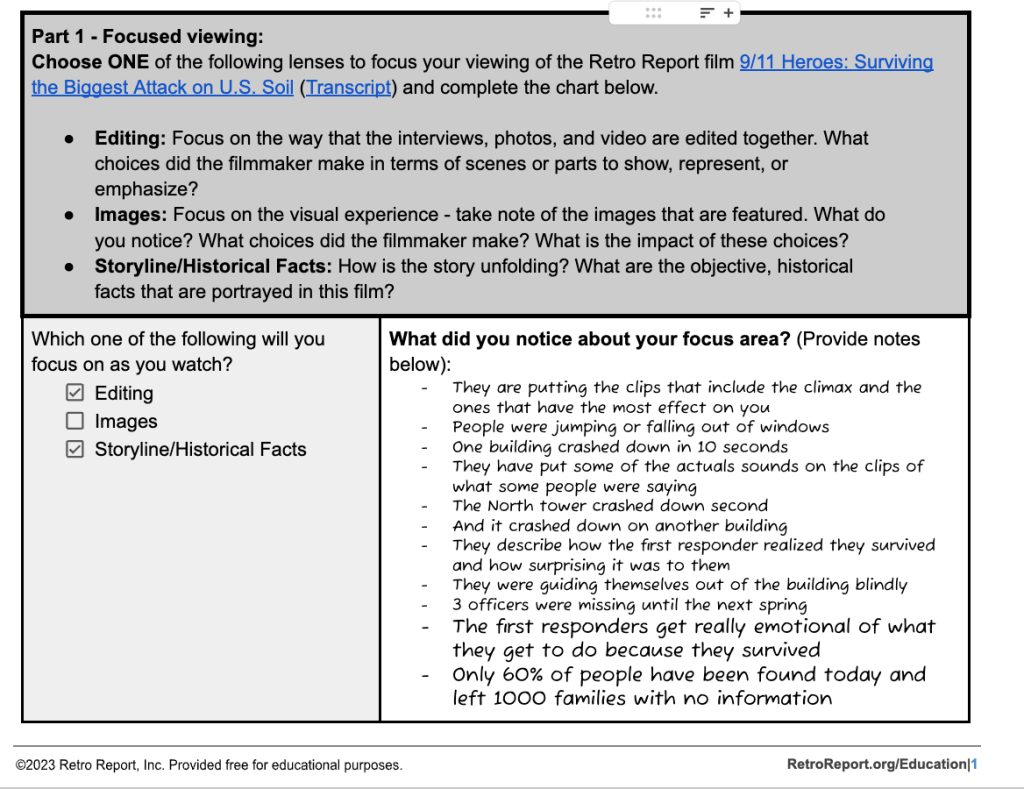

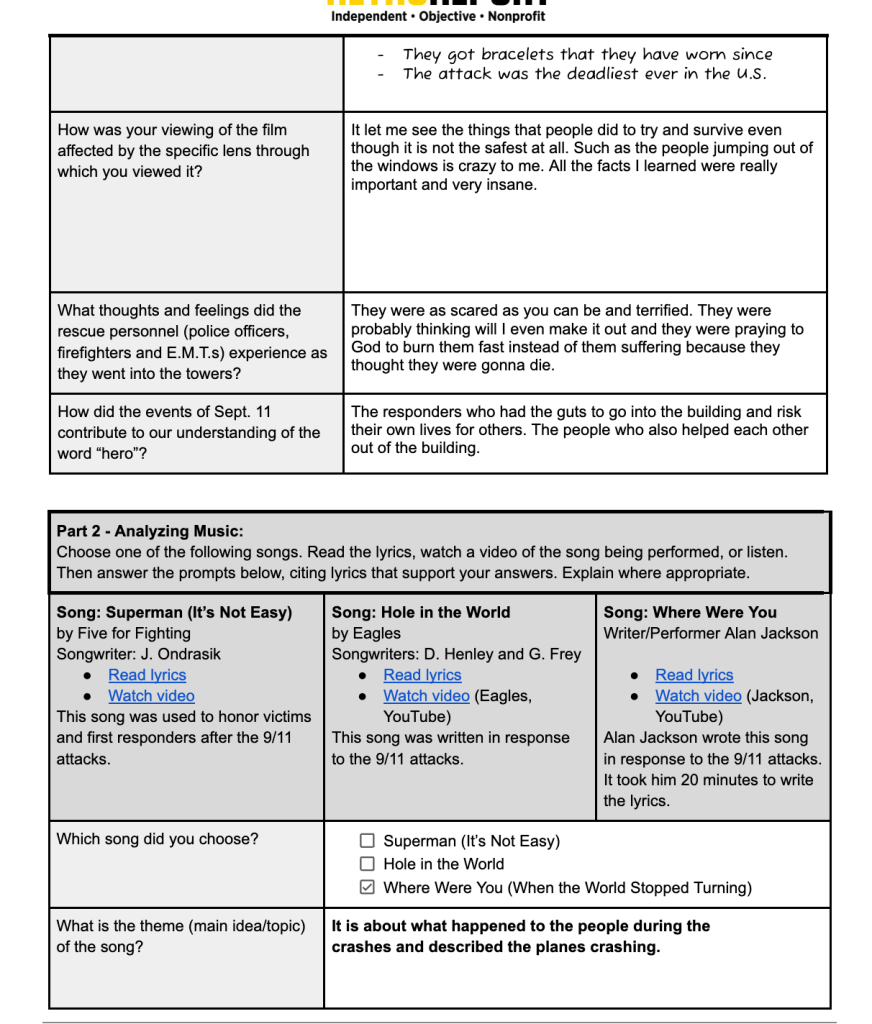

I set aside Thursday to focus on 9/11. I found a powerful Retro Report lesson with the objective: Analyze the impact of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 through different media sources. What I appreciated about this lesson is that it focused less on the events themselves and more on the heroes of 9/11 and the impact felt by the country afterwards. The main thread was exploring how Americans coped and grieved in the aftermath.

This one hit home for me. At 42 years old, I lived through that day, and I could share my perspective with students. For example, there was a song analysis portion where students chose one of three songs: Superman by Five for Fighting, Hole in the World by the Eagles, or Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning) by Alan Jackson. I told them how Jackson’s song was one I leaned on at the time to help process what happened. I was able to connect with them in a way that felt authentic and personal.

Another part of the lesson had students analyze Mike Piazza’s iconic home run or President Bush’s first pitch at the Yankees game. There was also an introductory video created by Retro Report that students could view from one of three lenses: editing, imagery, or stories. I did cut a few activities to fit our schedule, which in hindsight I probably should have left in, but even with that the lesson was meaningful. I had thought about layering EduProtocols into it but decided to keep the original structure, and it worked.

What struck me most was how engaged the students were. Many admitted they had never studied 9/11 in depth before. They were curious, asking thoughtful questions, and processing the material in ways that impressed me. Instead of the blackout poetry originally suggested, I had them create a six word story about how Americans coped and grieved. Their responses showed just how much they were thinking and feeling. It was one of those lessons where the kids carried the learning, and I was just guiding them along.