This week was a weird one heading into winter break.

Monday started as a two-hour delay, but the cold did not play nicely with the salt. Roads iced over, conditions got worse, and the day was eventually called off. Over the weekend, I had a freak accident and hit my head, which led to concussion symptoms. Headache and dizziness lingered into Monday and Tuesday, so I missed school on Tuesday.

Then Thursday morning hit. I woke up at 2 a.m. with an awful pinched nerve in my shoulder. Sometimes the pain is manageable. Sometimes it creeps up to a seven or eight. This one was a solid seven or eight. I tried to push through and go in anyway, but I could not make it. I left early and went to urgent care, and I am glad I did. The pain is gone.

Because of all that, this was not a week to start anything new. Instead, I kept it simple. We focused on one core question: why the British lost the Revolutionary War. We did not get into individual battles, specific people, or detailed comparisons between the two sides. This week was about framing the story and building understanding before the details.

Tuesday

Tuesday was about finishing strong.

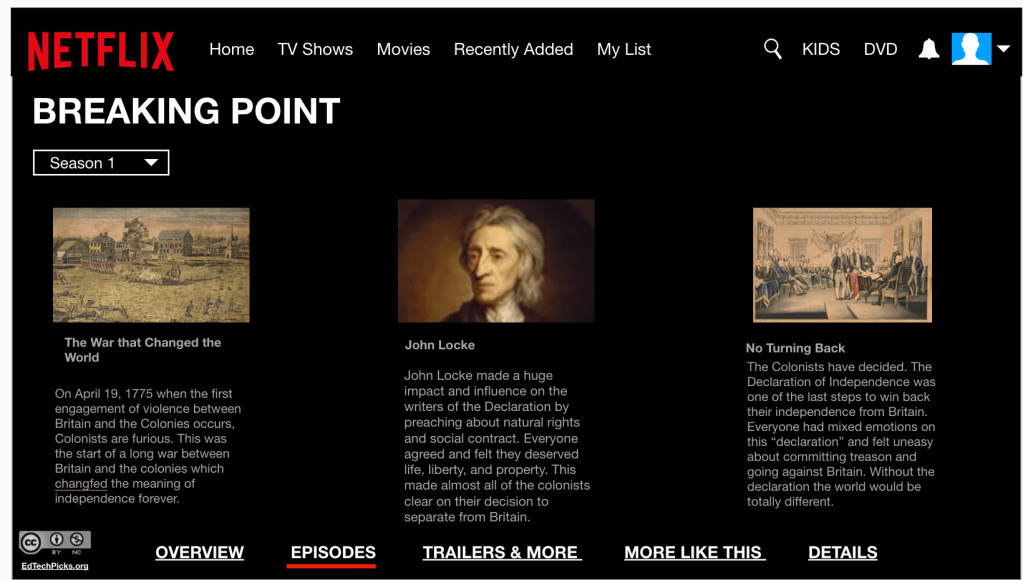

Students wrapped up their Netflix-style assessment for the Declaring Independence unit. I had very clear instructions typed up, and everything centered on one guiding question: what convinced the colonists that independence was worth the risk?

Each “episode” had a purpose.

Episode one focused on Lexington. Not just as a battle, but as British soldiers acting as police, enforcing laws, and ultimately killing colonists. We framed this as a civil conflict where natural rights were being violated. That moment mattered because it shifted the relationship. This was no longer about protests or complaints. Something had broken.

Episode two moved into ideas. John Locke and Thomas Paine. Natural rights and the social contract. But just as important was Paine’s ability to communicate those ideas in a way regular people could understand. Independence was radical. Paine made it relatable. He helped people see themselves in the argument and believe it was possible.

The final episode centered on the Declaration of Independence. The point of no return. Once that document was signed, there was no walking it back. The risk was real, but so was the commitment.

Looking back, it almost follows a hero’s journey without actually being one. A problem emerges. Beliefs are challenged. A decision is made that changes everything. Not because it fits a template, but because that is often how history actually unfolds.

Wednesday and Thursday

Wednesday and Thursday were about keeping things simple and intentional.

I did not have the time or the capacity this week to dive into Revolutionary War battles or a long list of people. I also did not want to be staring at screens because of the concussion. So instead of forcing something new or flashy, we slowed things down and went analog.

We did a paper-based stations activity built around one question: Why did the British lose the Revolutionary War? Students rotated through eight stations with an organizer, pulling evidence and ideas from a mix of primary and secondary sources. They read letters, watched a short video, and analyzed different explanations without me front-loading anything.

Before we started, I told them why I designed the lesson this way. Three years ago, a student asked me, “Mr. Moler, did we win the Revolutionary War?” That question stuck with me. It was a reminder that what feels obvious to us as adults or teachers is not always obvious to students. I wanted to make sure I covered my bases and made it clear that yes, the colonies did win.

I also explained that I could have framed the lesson as why the Americans won. Instead, I intentionally framed it as why the British lost. The most powerful military in the world lost to a group that, on paper, looked untrained, unorganized, and outmatched. That framing creates curiosity. It forces students to think deeper about strategy, geography, leadership, motivation, and mistakes rather than just memorizing victories.

Students used the stations to build their own explanation and then wrote a clear response answering the question. No slides. No devices. Just thinking, reading, and writing.

That lesson carried into Thursday.

For early finishers, I pulled out a John Meehan lesson that works like a choose-your-own-adventure through the life of a soldier. Students learned about training, pay, food, daily conditions, and how soldiers actually fought. I paired it with a Sketch and Tell-O, where students drew one idea and shared one thing they learned.

It was low-tech, calm, and exactly what this week needed.

Friday

Friday was controlled chaos in the best possible way.

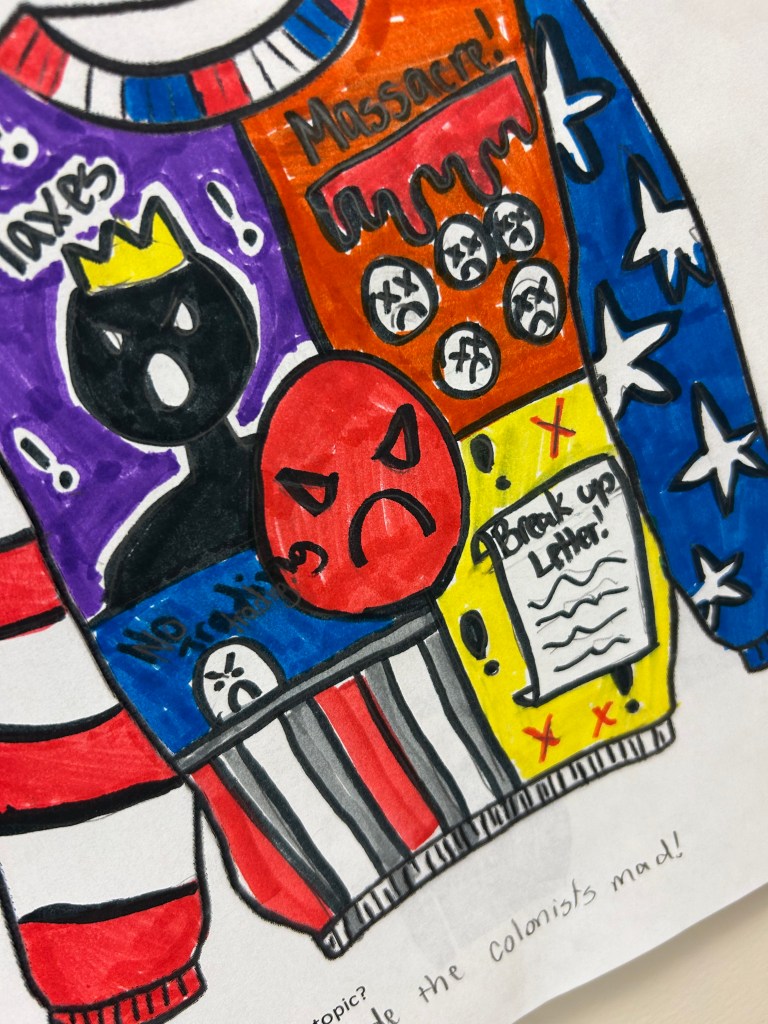

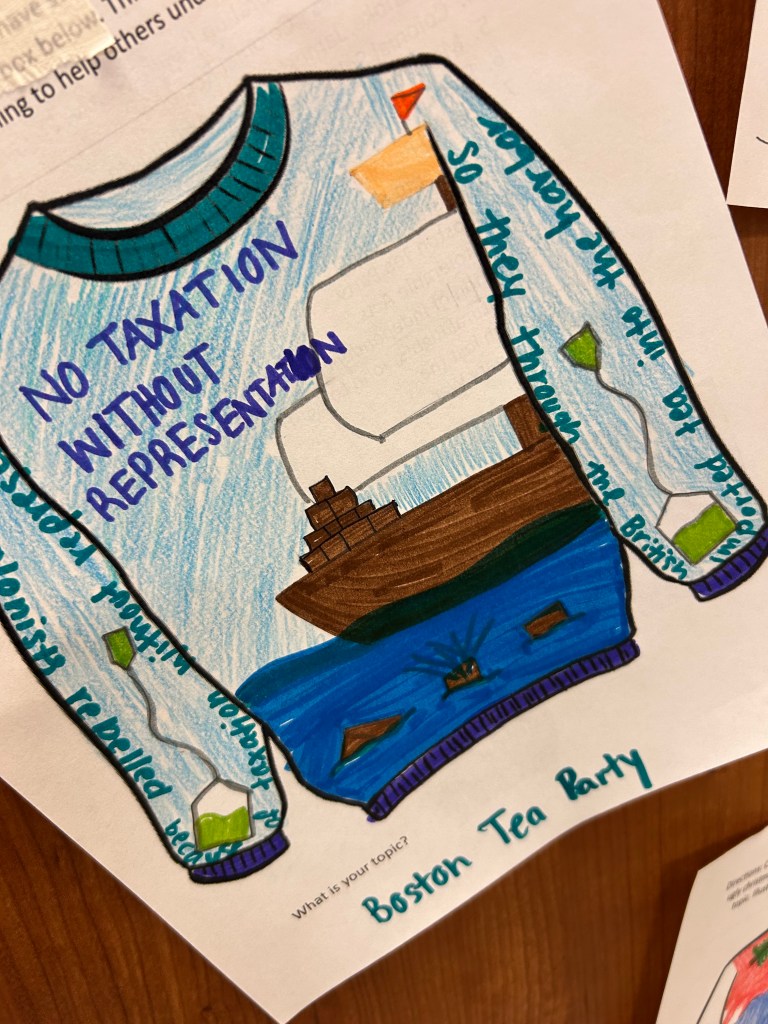

We did an ugly Christmas sweater party, but not the store-bought kind. We made them history-style. Students could choose any topic we covered during the first part of the school year and turn it into an ugly sweater design. Ideas were everywhere. Colonization, natural rights, mercantilism, battles, documents. Markers, paper, and laughter took over the room.

At some point in the middle of all this, a group of students started trying to draw me. Then they tried to draw me as George Washington. That is when I said the most 2025 sentence I have probably said all year: “ChatGPT can do that.”

I took my face, took George Washington’s face, and had ChatGPT merge them together. Then I turned it into a coloring page. It was ridiculous. It was hilarious. And the kids lost it.

More than anything, it felt like the perfect way to end the first half of the school year. Creative. Low pressure. Connected to content. A reminder that learning does not always need to be heavy to be meaningful. Sometimes it just needs to be human.

Heading into winter break, that felt right.

Lessons for the Week

Tuesday – Netflix Template, Netflix Directions

Wednesday – Rev. War Stations, Rev War Organizer

Thursday – Life of a Soldier, Sketch and Tell-o

Friday – Ugly Sweater Template