Monday

We kicked off the week by jumping straight into one of the most confusing and debated moments in early American history, the Battle of Lexington. The goal wasn’t just to learn what happened, but to help students build their own interpretations using evidence, perspective, and context. And honestly? Monday delivered.

A Documentary Hook

We opened with a three minute clip from the brand-new Ken Burns American Revolution documentary. I paused right as the first shot cracked across the screen. That moment became the anchor for everything that came next.

DIG Sources + 3xPOV

Students shifted into the Digital Inquiry lesson and worked through the primary sources. This is where the magic of 3xPOV really showed up. With two minutes per perspective, British soldier, Minuteman, and eyewitness, they built quick, evidence-based claims to explain what happened on Lexington Green.

Their writing showed real thinking:

- Students picked up on how quickly things escalated.

- They noted that both sides described the other as the first to act.

- Many picked up on fear, confusion, miscommunication, and split-second choices.

The 3xPOV sheets became messy, thoughtful, and honest—exactly what you want when you’re teaching kids how historians work.

Revisiting the Clip

Once students had shaped their ideas using the sources, we returned to the documentary and watched the next stretch. This time, they were watching with purpose. They weren’t just taking in the story, they were comparing interpretations, checking details, and refining what they thought happened.

That second viewing hit differently. You could see lightbulbs turning on as students layered new information onto their earlier ideas.

Back to the Compelling Question

Everything we did on Monday came back to the heartbeat of the unit: What convinced the colonists that independence was worth the risk?

Students started connecting Lexington to the bigger picture of natural rights, fear of losing self-government, and the sense that British actions were crossing a line. A few student responses from the day captured that shift:

- “They believed Britain was taking away their natural rights and threatening their lives.”

- “If they lost self-government, they had nothing. That’s what convinced them to fight.”

You could feel the unit starting to come together. Not because students memorized facts, but because they experienced how a single moment in history can change everything.

Wednesday

Wednesday was one of those beautiful 30 minute classes where everything had to be tight, intentional, and fast moving. The goal was simple: build student understanding of John Locke and connect his ideas directly to our compelling question about independence being worth the risk.

Frayer x2: Enlightenment + Locke

We opened with a quick double Frayer Model, one for the Enlightenment and one for John Locke. Students worked to define the ideas, identify characteristics, and connect them to symbols. Even in a short block, you could see the shift. Students started recognizing that the Enlightenment was not just old European thinking, but a spark that reshaped how people viewed rights, power, and authority.

Parafly Meets Sketch and Tell / Emoji Kitchen

Next, we moved into Parafly, paraphrasing definitions for natural rights and social contract. Instead of stopping at words, students paired their paraphrases with visuals through Sketch and Tell or Emoji Kitchen.

This is where things clicked. The images pushed them to internalize the meanings.

- Natural rights became images of protection, individuality, or freedom

- Social contract became governments chosen by the people, ballots, or agreements

Their sketches said just as much as their sentences.

Putting It All Together

To close the loop, students answered our supporting question: How did John Locke’s ideas influence the colonists in their dispute with the British government?

Their thinking showed real growth in just 30 minutes.

- They connected the ideas of ignored rights to the colonists’ rising frustration.

- They recognized that Locke offered options, the idea that people could question, replace, or revise a government that violated their rights.

- They linked Enlightenment philosophy to colonial action: “suppression was not their only choice.”

Even in the short class period, students stacked multiple exposures: vocabulary, visuals, paraphrasing, and application. They walked out with a clearer understanding of why ideas mattered as much as events.

Thursday and Friday

To close the week, we shifted from battles and philosophies to one of the most influential voices of the entire Revolution. This was our introduction to Thomas Paine and Common Sense, and once again the Ken Burns documentary became the perfect anchor. This was the third time we used it in this unit, and it continues to be such a valuable tool. PBS keeps posting clips, and if they keep doing that I will keep finding ways to use them. The storytelling is incredible.

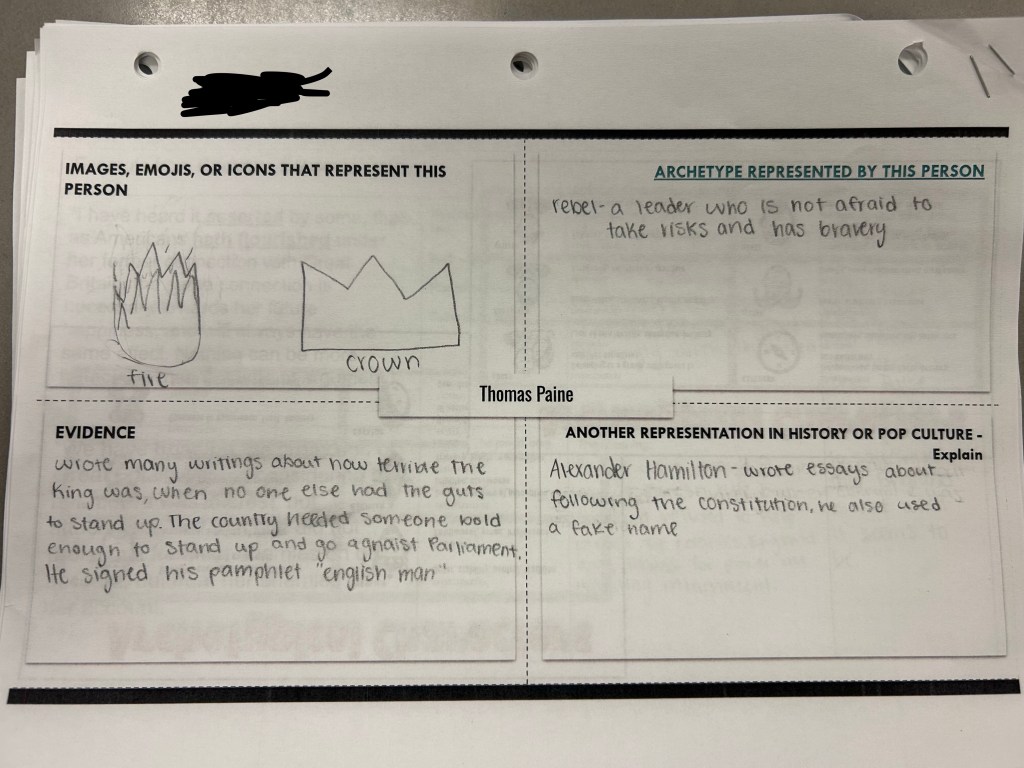

Archetype Four Square with the Documentary Clip

We opened with a four minute clip on Thomas Paine. Students had the Archetype Four Square template in front of them on paper, and after watching the clip they talked in groups to answer a simple question: which archetype fits Paine?

Their answers were all over the map in the best possible way.

- Some saw him as a rebel.

- Others argued he was a creator.

- A few made a case for sage.

- One group claimed he was basically a magician because of the way he transformed public opinion.

Everyone had evidence and everyone had a justification. It was a strong discussion that showed how open ended archetype work can be when the content is rich.

Reading Paine’s Words for Ourselves

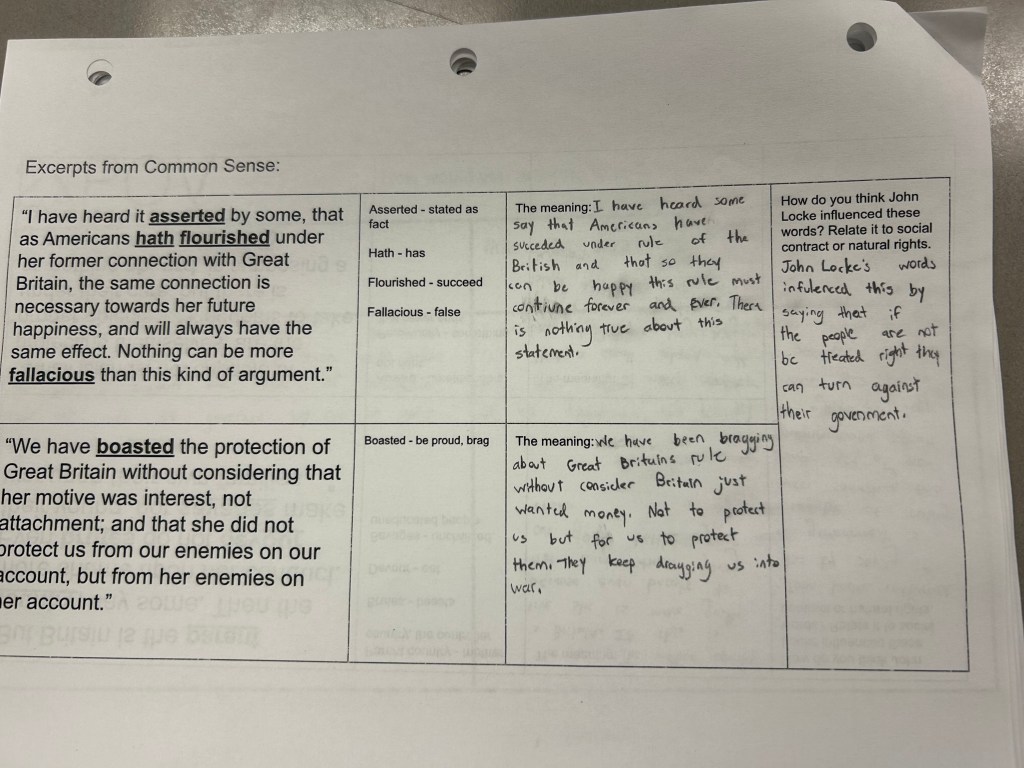

Next, students moved into reading excerpts from Common Sense. One excerpt connected directly back to the documentary clip, where historians mentioned that Paine called the king a literal beast. Students lit up when they saw it in print. It helped them understand that Paine’s writing was bold, emotional, and designed to stir people into action.

Using Parafly, students translated Paine’s original words into clearer language. The goal was not to simplify the ideas, but to make them accessible so the message could stand out.

I asked students, “Which event must have been on Paine’s mind when he wrote that?”

Their retrieval was strong. Boston Massacre. Tax laws. Early British crackdowns. They pulled events from previous lessons and connected them to Paine’s anger and urgency.

Then we pushed further. Students responded to How do you think John Locke inspired these words?

They began seeing what historians always emphasize. Ideas do not appear out of nowhere. One moment shapes the next, one writer builds on another, and everything connects.

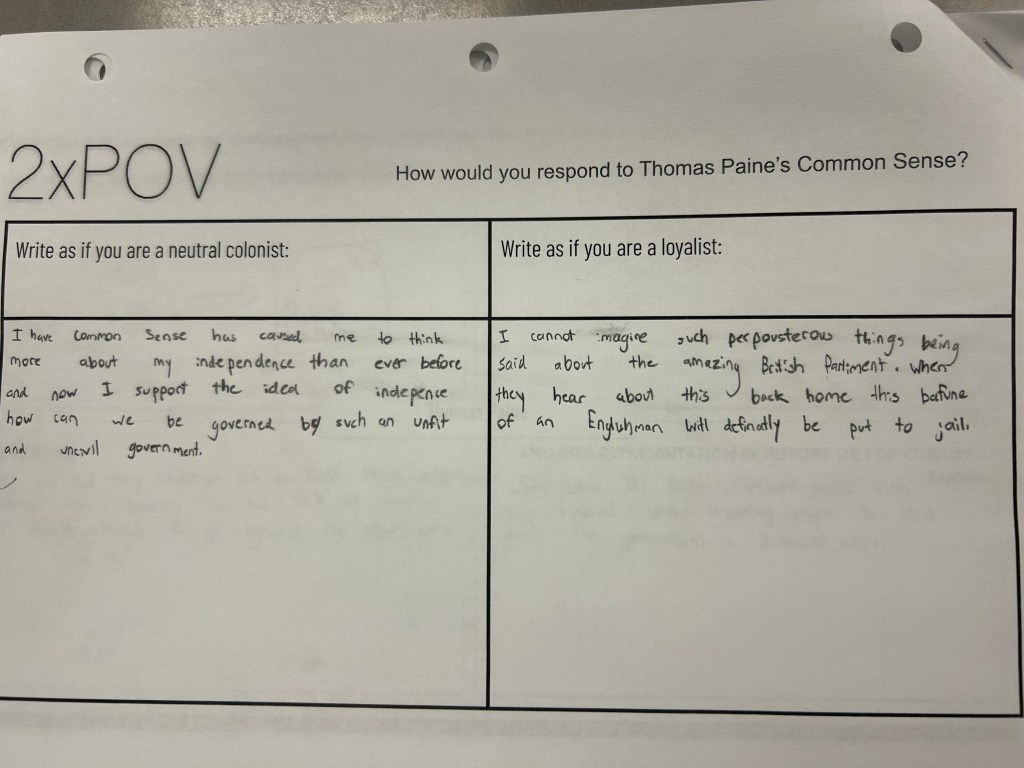

Ending the Week with a 2xPOV and a Mystery

To close the lesson, we returned to the consistency of POV writing from earlier in the week. Students wrote for three minutes from the perspective of a neutral colonist answering: If you were a neutral colonist and read Common Sense, would it sway you?

Then they switched roles and wrote as a loyalist. If you read Common Sense as a loyalist, how would you feel and what would you say?

Once students finished their writing, I set up the final moment of the day. Sitting on a small stool in the center of the room were a set of fake bones. Students walked in and noticed them immediately, but I did not explain them until the end. After we wrapped the 2xPOV, I told them the story of Thomas Paine’s bones, scattered across the world after his death because of the controversy surrounding his life and ideas.

It was the perfect unexpected hook to end the week. Students left the room talking about Paine, his writing, his influence, and now his bones. It tied everything together in a way that was memorable and a little strange, which is exactly how good history class should feel.

Lessons for the Week

Monday – Battle of Lexington (DIG), 3xPOV

Wednesday – John Locke Rack and Stack

Thursday and Friday – Thomas Paine Rack and Stack