This week in 103 was all about building a bigger story. We moved from Samuel Adams to the Stamp Act protests, into the Townshend Acts, and finally circled back to the Boston Massacre with fresh eyes. Even though we had shortened classes on a few days, the structure of the protocols kept things tight and focused. Students were constantly reading, creating, discussing, and explaining. What stood out most was how each day layered onto the next. By Friday, students could see how one decision in Parliament led to another reaction in the colonies, which led to more tension, and eventually to violence in Boston. It was a full week, but a good one, and the kids handled the thinking really well.

Monday

We kicked off the week with 30-minute classes, and I always laugh a little when people insist you “can’t learn anything” in that amount of time. With EduProtocols, 30 minutes is plenty. If anything, the shortened periods force clarity: What matters? What’s the essential move? What can students actually do in that window?

For Monday, that essential move was introducing Samuel Adams. The name is familiar, but students usually know very little about him. Since we were jumping into new content, I wanted fast reps on vocabulary and core ideas, so we started with a Blooket. Quick, fun, and a fast way to frontload the content they would need in the next task.

From there, we moved into an Archetype 4 Square. I dropped a short bio of Samuel Adams into the center, and students filled the quadrants:

- a symbol for Samuel Adams

- an archetype that fits him

- evidence from the reading defending that choice

- someone from history or today who connects to him, along with an explanation

That last box is where I am still coaching. Students are decent at choosing a comparison person, but they forget the explanation. Easy fix. I might just add a short reminder directly in the quadrant (“Explain why this person connects”) so the prompt stays on their radar even when they start typing.

The conversations afterward were the real payoff. Students shared the archetypes they chose such as Rebel, Sage, and Creator, and they had strong reasons behind each one. Rebel was easily the most common, but some students pushed deeper and defended more unexpected angles. For a short class, it produced some of the best thinking of the day.

Tuesday

Frayer Model

Tuesday was a full rack and stack on the Stamp Act protests, and it flowed really well from one protocol to the next. We started with a Frayer Model on the Sons of Liberty. I provided the definition, and students paraphrased it in their own words. In the bottom sections, they added four characteristics from a short reading I linked to the center term, and then they added a picture. It was a quick way to anchor who the Sons of Liberty were before moving into the bigger story.

Sketch and Tell O

Next, we moved into a Sketch and Tell O paired with a reading about the Stamp Act protests. Students used Emoji Kitchen to create symbols and images that represented the different ways colonists protested. Emoji Kitchen lets students combine emojis in creative ways, and it always leads to stronger thinking and clearer explanations. After creating their images, students explained how each symbol connected to the protests.

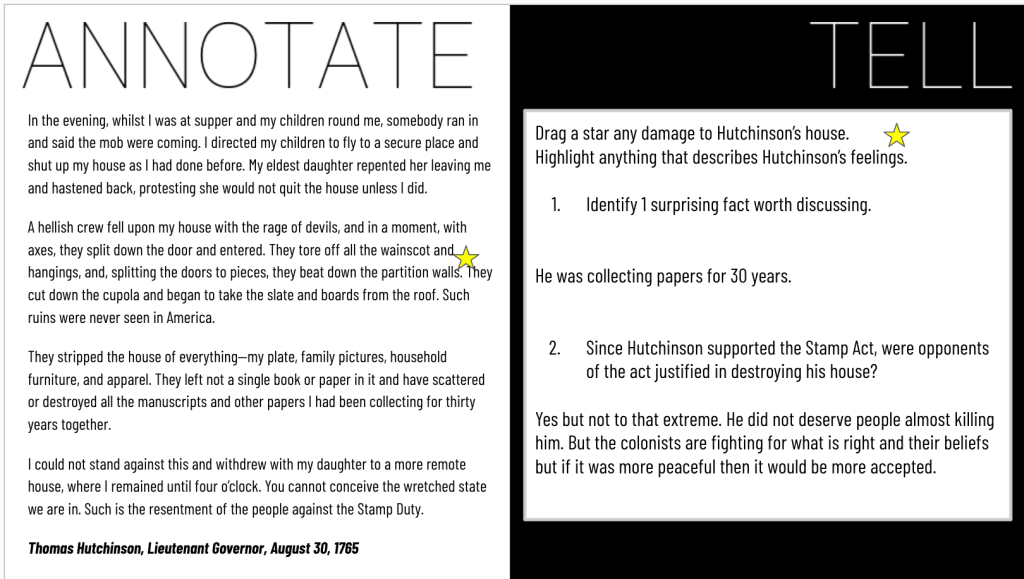

Annotate and Tell

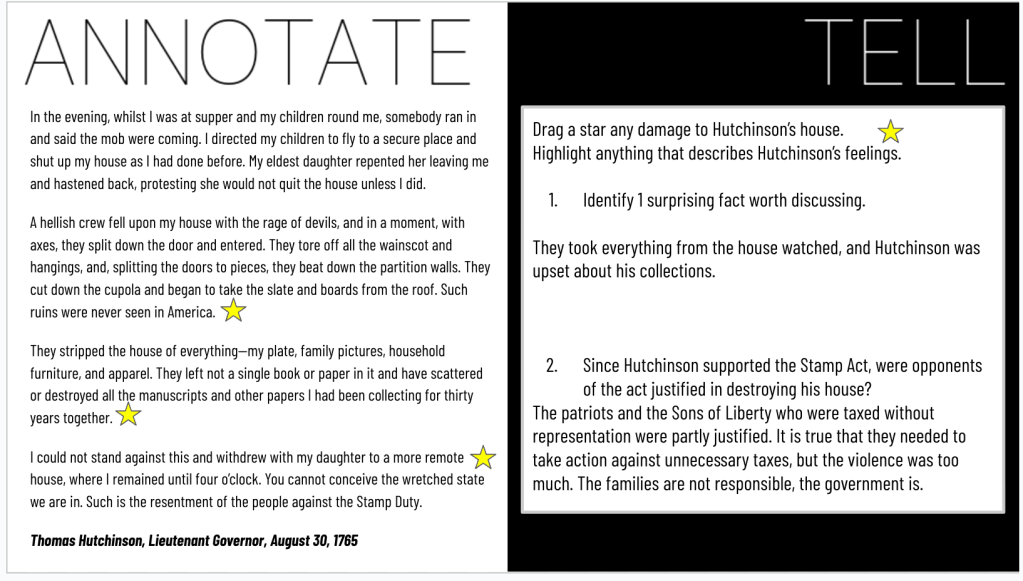

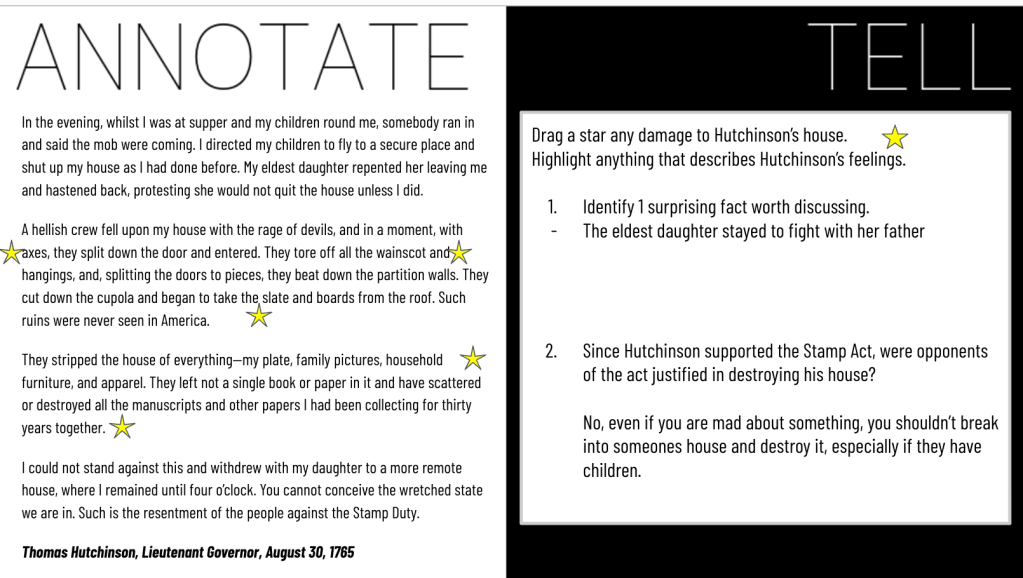

The reading mentioned Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson and the attack on his home, so that became our bridge into the next layer. I gave students a primary source excerpt from Hutchinson’s letter describing the destruction of his house, and we used an Annotate and Tell to slow down and analyze it. Students had to drag a star to any line showing damage to the house, highlight anything that showed Hutchinson’s feelings, and identify one surprising detail. Then they weighed in on the big question. Since Hutchinson supported the Stamp Act, were the protesters justified in destroying his home?

2xPOV

We wrapped the lesson with a 2xPOV. Students selected two perspectives from the list Thomas Hutchinson, a Sons of Liberty member, a member of Parliament, or Samuel Adams and wrote from those viewpoints about the protests. I linked Snorkl for immediate feedback so students could revise on the spot.

All of this moved from DOK 1 to DOK 3 in one 45 minute class period. Students went from paraphrasing and identifying to creating symbols, analyzing a primary source, and finally writing from multiple viewpoints. It was a short class with a lot of thinking packed into it.

Wednesday and Thursday

Thin Slide Faceoff

We were back to shortened classes again, so I kept things tight and intentional. We shifted into the Townshend Acts and started with a Thin Slide Faceoff. Students read a short overview I linked to the slide, then created a thin slide that captured the Townshend Acts in three minutes with one picture, one word or phrase, and a short explanation. Fast, simple, and it got them thinking.

Next, they read about natural rights and made another thin slide with the same constraints. After both slides were done, we moved into the faceoff part. Students paired up and talked through this question: What is the connection between natural rights and the Townshend Acts?

The conversations were impressive. Students worked together to create a final thin slide that showed the connection they saw. Many noted that taxing without representation violated natural rights, but they still needed practice explaining why. That set us up perfectly for the next protocol.

CyberSandwich

To push their thinking further, we transitioned into a Cyber Sandwich using the Massachusetts Circular Letter written by Samuel Adams and James Otis Jr. This document is incredibly important for understanding colonial resistance, yet I have never seen it in a textbook. Students independently read the letter and underlined any mention or hint of natural rights.

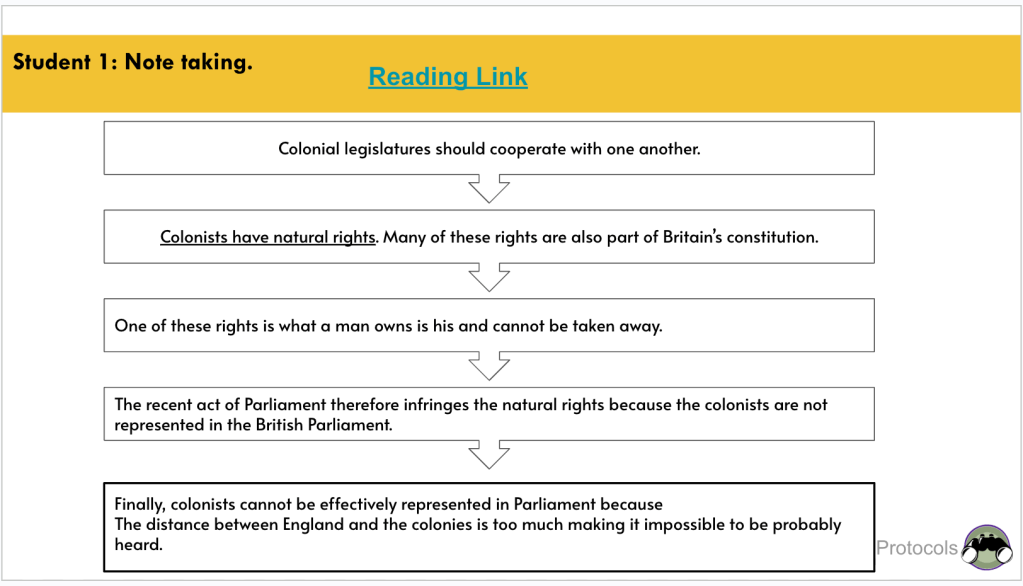

After reading, they completed a flow chart that matched the structure of the letter. The chart had five parts:

- Colonial legislatures should cooperate with one another.

- Colonists have natural rights, and many of these rights are also part of Britain’s constitution.

- One of these rights is…

- The recent act of Parliament therefore…

- Finally, colonists cannot be effectively represented in Parliament because…

Students struggled with this at first. Many missed Samuel Adams’ main point: that taxing without representation violated the natural right of property. We paused for a discussion about what “property” meant in the 1760s. Students assumed it meant houses and land. We talked through how property also includes money and the things you earn through your own labor. Once that clicked, the flow chart made a lot more sense.

Students then shared their flow charts with a partner to compare thinking and clean up misconceptions.

Snorkl Writing

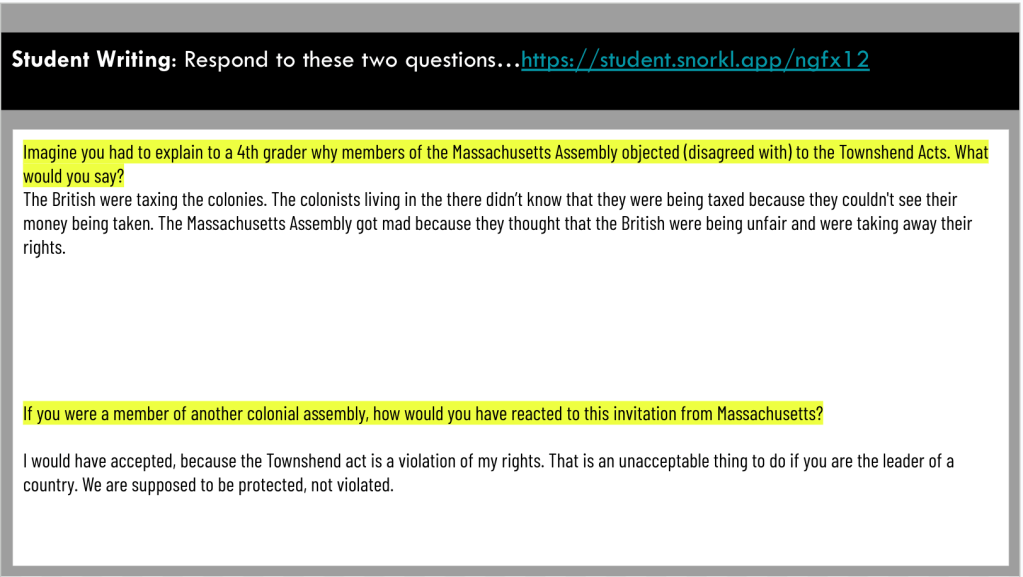

We wrapped both days with two Snorkl prompts:

- Imagine you had to explain to a 4th grader why members of the Massachusetts legislature objected to the Townshend Acts. What would you say?

- If you were a member of another colonial legislature, how would you have responded to this invitation from Massachusetts?

Because students needed more time to fully understand the Circular Letter, we stretched this work across both Wednesday and Thursday. The struggle was productive and necessary. By slowing down and doing it over two days, students finally saw how natural rights, property, and representation all connected.

Friday

Number Mania plus Main, Side, Hidden

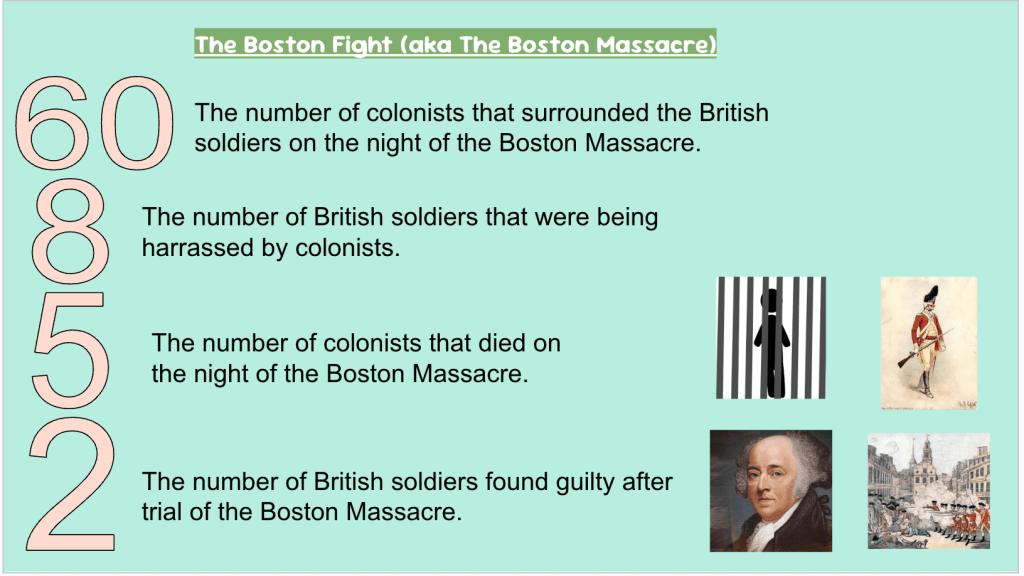

We wrapped the week by jumping into the Boston Massacre. Students had already studied it earlier in the year through the Paul Revere engraving, so I needed to come at it from a different angle. Instead of treating it as an isolated event, we connected it to the larger story we had been building all week through the Townshend Acts.

We started with a quick narrative review. Parliament became angry about the Massachusetts Circular Letter, the royal governor dissolved the Massachusetts Assembly, and Britain sent more soldiers to Boston to keep order. More troops meant more friction, and more friction meant the situation was almost guaranteed to explode. That set the stage for the Boston Massacre.

For the lesson, students created a Number Mania using four numbers that explained the story of how tensions escalated into the Boston Massacre. They also had to give their slide a more truthful title for Paul Revere’s engraving, since his version of the event was far from accurate.

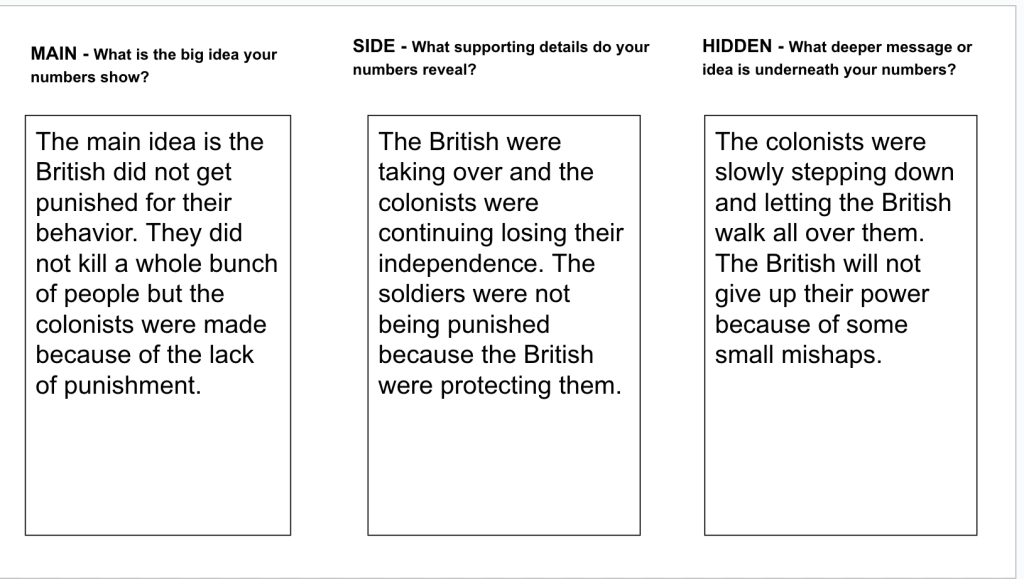

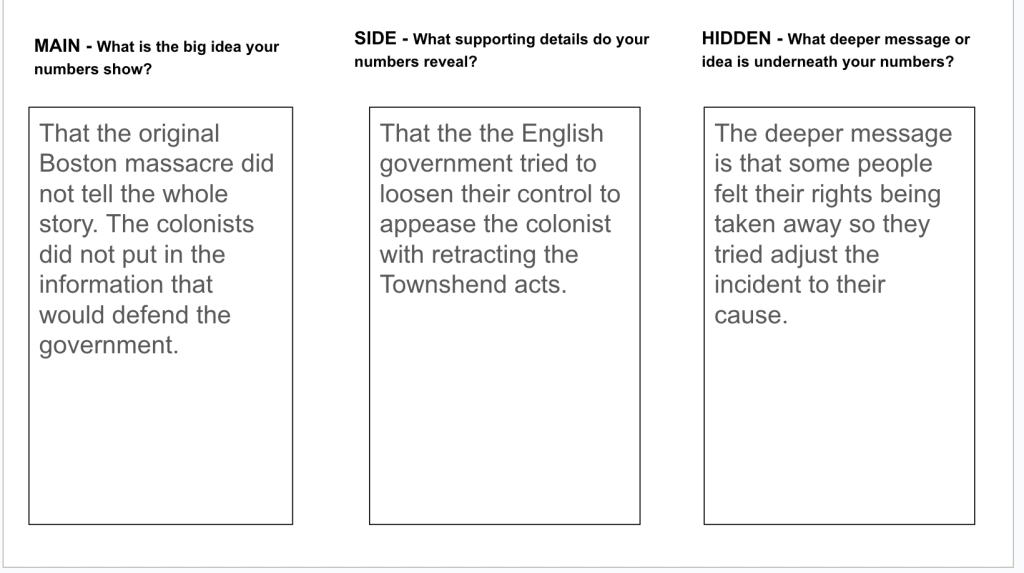

After students built their Number Mania slides, we added a layer from the Main, Side, Hidden routine. Since this was new for many students, we slowed down and talked through each part:

MAIN

This is the central story your numbers tell. What is the big idea? What is the main takeaway someone would understand from your four numbers?

SIDE

These are the details happening alongside the big idea. They may not be the headline, but they help explain why the main story happened. Side stories often introduce other people, factors, or influences that add depth or context.

HIDDEN

This is the deeper, less obvious layer. What is happening under the surface? What truth or tension isn’t immediately visible in the main or side stories? This could be something about power, fear, propaganda, rights, or motives.

Explaining these three layers helped students go beyond listing facts. They started thinking about the Boston Massacre as more than a street fight. They noticed how propaganda shaped reactions, how fear influenced both sides, and how anger over natural rights violations had already created a powder keg before the first shot was fired.

It was a strong way to end the week. Students used numbers to build a story, then used Main, Side, Hidden to deepen it. The routine helped them see that history is never just one story. There are always layers.

Lessons for the Week

Monday – Samuel Adams Archetype

Tuesday – Stamp Act Protest rack and stack

Wednesday/Thursday – Massachusetts Circular Letter rack and stack

Friday – Boston Massacre Number Mania