This week in 103 was packed with movement, discussion, and meaningful writing. The lessons built on each other, using EduProtocols that pushed students to analyze, connect, and create rather than memorize.

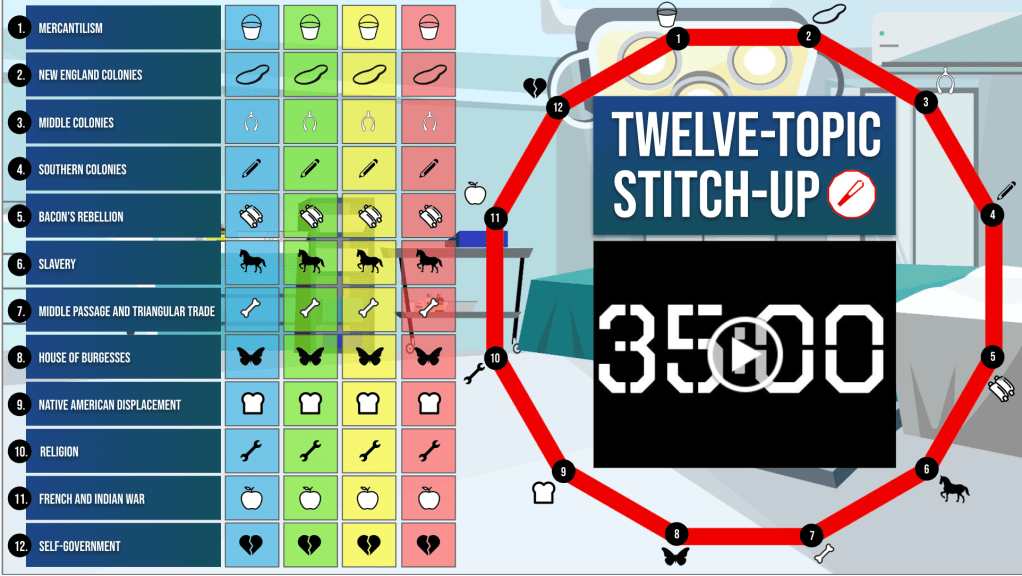

We used CyberSandwich for deep reading and partner discussion, Snorkl for instant writing feedback, SWBST Sketch and Tell to help students visualize and summarize key events, Map and Tell to analyze spatial change, and Twelve-Topic Stitch-Up to review and connect ideas across multiple units. Each protocol gave students a clear structure for thinking while keeping engagement high.

It was a week that blended analytical thinking with creativity and reminded me how powerful structure and feedback can be when they work together.

Monday

Starting with Context

We began with two short readings that set the stage. The first explained how England’s government evolved from absolute monarchy to limited government, tracing the Magna Carta, Parliament, and the English Bill of Rights. The second showed how those same ideas carried into colonial life through the House of Burgesses, the Mayflower Compact, and New England town meetings.

Each reading made one thing clear: freedom in the colonies was built on English ideas, but not everyone got to share it.

Building Understanding through CyberSandwich

Students partnered up for a CyberSandwich. Partner 1 read and took notes on England’s ideas, focusing on what limits were placed on the king and how citizens gained a voice. Partner 2 focused on how the colonies used or changed those ideas. Then they met in the middle to discuss who had power and who was left out.

It’s an activity that’s always been strong for collaboration and comprehension, but this time, I layered in something new.

Snorkl: Feedback That Actually Matters

In the past, students would write their CyberSandwich response, turn it in, and maybe get my feedback a few days later. This time, I paired it with Snorkl AI feedback, and everything changed.

Instead of waiting, students got instant, specific feedback on their writing. Snorkl scored their responses out of four and offered suggestions they could act on immediately. Suddenly, the classroom energy shifted. Students weren’t done after one draft; they wanted to improve.

Some rewrote their paragraphs four, five, even eight times, chasing that 4 out of 4 score. I told them that if they earned a 3 or a 4, they were finished. But if they landed on a 1 or 2, they had more work to do. It wasn’t about perfection; it was about progress.

And it worked. Students who rarely revised were reading their feedback out loud, asking questions, and explaining their thinking to peers. For the first time, I didn’t have to beg for revisions. The feedback loop ran itself.

Why It Mattered

Teaching social studies from an analytical standpoint doesn’t lend itself to quick right-or-wrong answers. It’s about reasoning, evidence, and perspective, and that kind of learning thrives on feedback. I don’t have the time to personally give that level of feedback to thirty kids every day, but AI made it possible.

By the end of class, students weren’t just defining democracy or limited government; they were thinking like historians, weighing whose voices mattered and whose didn’t.

Tuesday

The Question That Drove the Lesson

Tuesday’s focus was one event that connected perfectly to Monday’s discussion on power and inequality: Why was Bacon’s Rebellion significant?

The McGraw Hill textbook began with the line, “Bacon’s Rebellion was significant because it showed the government could not ignore the demands of its people.” That statement sounds fine on the surface, but it misses the bigger story. I told students right away that there is more to Bacon’s Rebellion than a government not meeting the needs of citizens.

Starting with Context: Anthony Johnson’s Story

We started with a video from PBS about Anthony Johnson, one of the first Africans to arrive in Jamestown, Virginia. He had been enslaved but eventually earned his freedom, bought land, and even owned servants himself. For a time, he lived as a free man in a colony where race did not yet define status.

That part of the story always surprises students. They see early Virginia as a place where freedom was possible for some Africans, at least for a short while. But when Johnson’s land was later taken and his family declared “aliens,” it showed how quickly opportunity gave way to inequality. His story laid the groundwork for how racial boundaries hardened over time.

Building Understanding: Bacon’s Rebellion

After that, we turned to Bacon’s Rebellion itself. Students read a short story about the uprising and completed a SWBST Sketch and Tell. They identified the key elements of the story first before moving to visuals. I reminded them to read first, mark things up, type their captions, and add pictures last.

The focus was not just on what happened but on how people responded. Nathaniel Bacon and his followers were frustrated frontier settlers who felt ignored by Virginia’s wealthy leaders. But the real takeaway was what came after. The rebellion failed, but it scared the colonial elite. Leaders realized that poor whites and Africans had united around a common cause, and that was something they did not want to see happen again.

Putting It All Together: Cause, Catalyst, and Change

We shifted back to analysis through a CyberSandwich activity. Students read, took notes, and discussed how Bacon’s Rebellion became a catalyst for race-based slavery, even if it was not the direct cause. We talked about how laws soon began to divide people by race to prevent future uprisings that crossed color lines.

Their final task was to “Put it all together and fix this statement from the textbook in four or more sentences.” That line about the government not meeting citizens’ needs became a starting point, not the ending point.

I added a Snorkl link again for real-time feedback. Just like Monday, students were revising again and again, some four, five, even six times, until they reached a score of three or higher. Once they did, they were done. The difference this time was the level of insight. Students were not just repeating facts; they were explaining how power shifted, how fear drove change, and how one rebellion set the stage for race-based slavery.

Why It Mattered

Bacon’s Rebellion is one of those moments that is easy to oversimplify. Textbooks tend to flatten it into a story about poor farmers against a stubborn government. But when students saw how Anthony Johnson’s story connected to it, they began to understand the deeper truth. Bacon’s Rebellion was not just about government; it was about control.

Wednesday and Thursday

The Question That Drove the Lesson

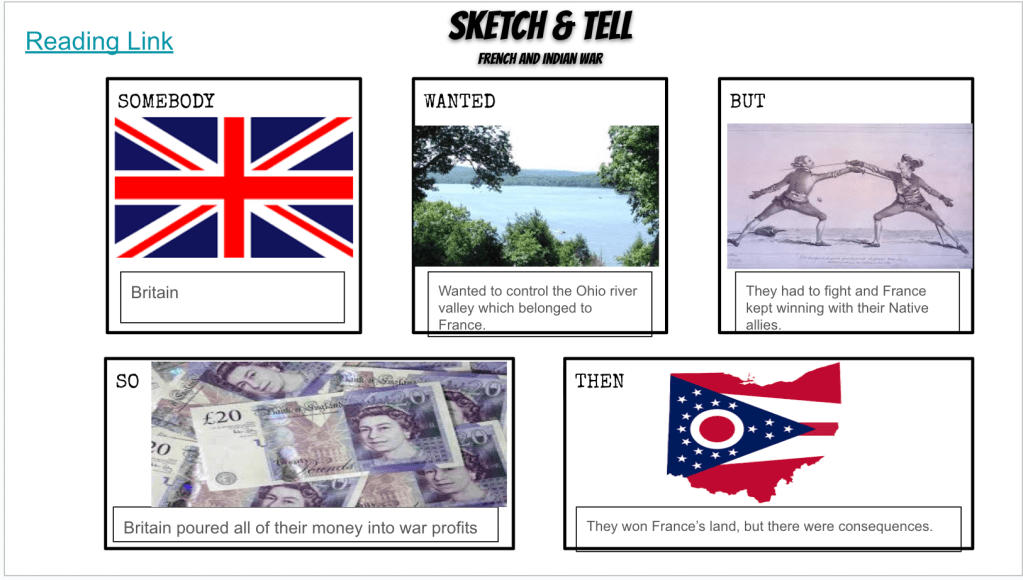

Our focus shifted to another rivalry that shaped opportunity and inequality in early America: How did the French and Indian War create opportunity for some and inequality for others?

It was a week built around maps, perspectives, and empathy. These were the kinds of lessons where my classroom setup really paid off. My room is arranged in clusters of three desks, which makes it easy for students to discuss, analyze, and collaborate. It feels good to be teaching this way again.

Starting with Context: Map and Tell

We began with a Map and Tell. Students analyzed a map of North America before and after the French and Indian War, tracing how land and power shifted. Within their small groups, they discussed two guiding questions:

- What major land and power changes happened after the French and Indian War?

- How might these changes have created new opportunities for some groups and inequality for others?

The conversations were rich. Students began noticing that while Britain gained territory, it also gained massive debt. Native American groups lost land and autonomy. The colonies suddenly found themselves both protected and restricted. The map itself became a visual story of winners and losers.

Reading and Representing: SWBST Sketch and Tell

Next, students read a short story that summarized the key events of the war and completed a SWBST Sketch and Tell. I reminded them again to read first, mark up important parts, type captions, and then add pictures. The goal was not to decorate but to make meaning visible.

This routine has started to stick. Students know what I mean when I say, “Read before you draw.” They are beginning to see that good visuals come from good comprehension.

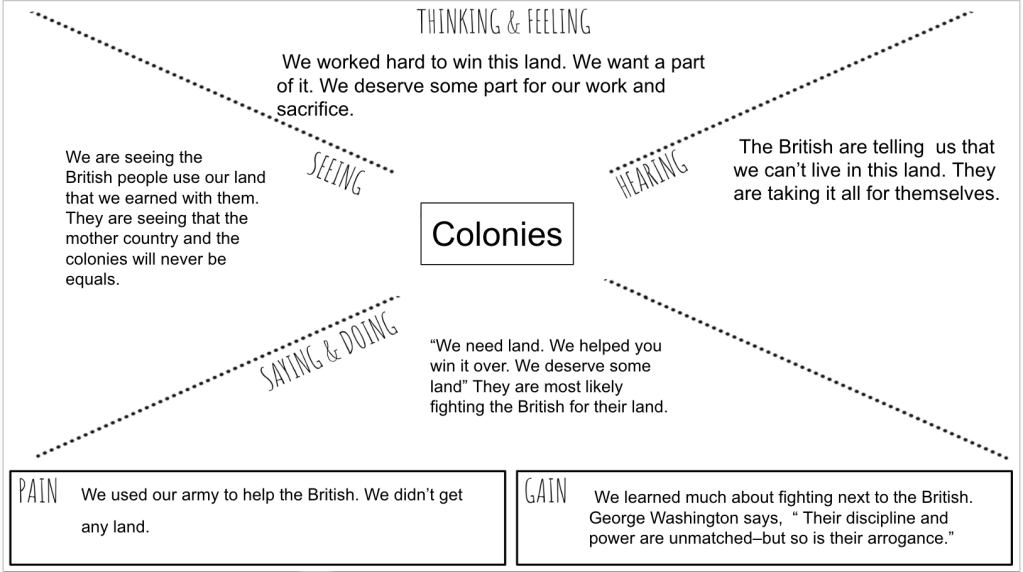

Multiple Perspectives and Emoji Fusion

After that, we moved into one of my favorite parts of the week. Students read four short perspectives about the war: one British, one French, one colonial, and one Native. Each voice told a different story about what was gained or lost.

Then came the creative twist. Using Emoji Kitchen, students fused emojis together to represent those gains and losses symbolically. It might sound simple, but the results were incredible. Some fused a broken heart with a mountain to show lost homeland. Others used a handshake with fire to represent uneasy alliances. Their creativity amazed me.

On the “Tell” side, students answered and discussed two reflection questions:

- Explain how your emojis show what each group gained or lost after the French and Indian War.

- What pattern or theme have you noticed from studying exploration, colonization, and power in North America?

The second question opened some of the best conversations we’ve had all year. Students started connecting back to earlier units, noticing how power and inequality have been constant themes from exploration through colonization.

Finishing with Empathy

In some classes, we had time to end with an Empathy Map. Students picked a side and took the thinking deeper, reflecting on how it might have felt to experience the outcomes of the war firsthand. In other classes, time was tight, so we skipped the empathy map and wrapped up with discussion instead.

Either way, students were doing what historians do best: analyzing patterns, making connections, and interpreting perspective.

Why It Mattered

These two days reminded me that visuals, creativity, and collaboration can turn complex history into something personal. The French and Indian War is often taught as a list of dates and treaties, but when students used maps, drawings, and emojis to show who gained and who lost, it became more human.

They saw that history is not just about what happened but about who it happened to. And that understanding matters more than any fact they could memorize.

Friday

The Question That Drove the Lesson

Friday was about bringing it all together. After a week filled with deep thinking about power, opportunity, and inequality, I wanted students to review in a way that matched the Halloween energy in the building. The goal was simple: make connections across everything we have learned so far and see how the pieces fit together.

Starting with the Energy

Halloween in middle school is pure chaos, so instead of fighting it, I leaned into it. We played Twelve-Topic Stitch-Up, a high-energy review that blended teamwork, laughter, and higher-level thinking. The classroom turned into an operating theater, with “surgeons” connecting major concepts from our unit and trying to keep a steady hand while doing it.

Each group selected one topic from the list and had to “stitch” it to four others by explaining how the ideas connected. They drew lines between concepts like Mercantilism, Bacon’s Rebellion, Slavery, Self-Government, and the French and Indian War. Each connection had to be explained clearly before they could call me over for a check-up.

If their connections and explanations were strong enough, they could send one group member to the front to extract an Operation game piece. The buzz of the board added another level of intrigue, excitement, and fun. Students were laughing, cheering, and thinking all at once.

It was loud, focused, and full of energy. I heard students making statements like, “Bacon’s Rebellion connects to Slavery because elites feared unity between poor whites and Africans,” and “Mercantilism connects to the Middle Passage because England’s wealth depended on trade routes powered by enslaved labor.”

What I Saw and Heard

What amazed me most was how much students remembered and how clearly they could explain their thinking. The discussions were full of evidence and reasoning, not just recall. I heard them pull together ideas from weeks of lessons on exploration, colonization, government, and war, and they were doing it with confidence.

At the same time, the activity revealed small misunderstandings I could immediately clear up. Some students mixed up the role of Parliament or misinterpreted the outcomes of the French and Indian War. Those moments became quick teaching pivots that helped sharpen understanding right on the spot.

Why It Mattered

Friday reminded me that review does not have to be passive. When students are active, competitive, and creative, they show what they truly understand. The Stitch-Up gave them a chance to demonstrate how power, opportunity, and inequality weave through every part of early American history.

The Operation game piece element turned a review into an event. It gave students a reason to cheer for one another, think more critically, and celebrate their learning.

By the end, the energy was still high, but so was the learning. It was the perfect way to end a wild week and a reminder that a good review day can still push students to think deeply.

Lessons This Week

Monday – Colonial Governments

Tuesday – Bacon’s Rebellion

Wed/Thursday – French and Indian War

Friday – 12 Topic Stitch Up