Week two felt like a reset button. Last week I tried to do too much too fast with Chromebooks, logins, and codes. It was overwhelming. This week, I went back to the basics. Paper, pencils, and simpler routines gave students (and me) the space to breathe. We still pulled out the tech: Quizizz for Fast and Curious, Google Slides for Thin and Thick slide, but we balanced it with Frayers, CyberSandwich, and Sketch & Tell-o on paper. That rhythm worked.

I also had a big curriculum shift confirmed. Originally, 6th grade was set for 7th grade content (ancient Rome and Greece), 7th grade for 8th grade content (early American history), and 8th grade for 10th grade content (modern American history). But over the weekend, it hit me my 8th graders had never learned early American history. How could they possibly jump straight into the modern era? I brought it up to my principal, and he agreed. So this year, both 7th and 8th grade are studying early America. Next year, 7th grade will move forward into modern America, and everything will be aligned again. It’s the right move, and it gives me time to prep for a brand-new course I’ll be teaching down the road.

Monday – Sources Rack and Stack

Wednesday – Lunchroom Fight 2

Thursday – Historical Thinking with Molly Pitcher Painting

Friday – John Brown Bias

Monday – Sources and Sourcing

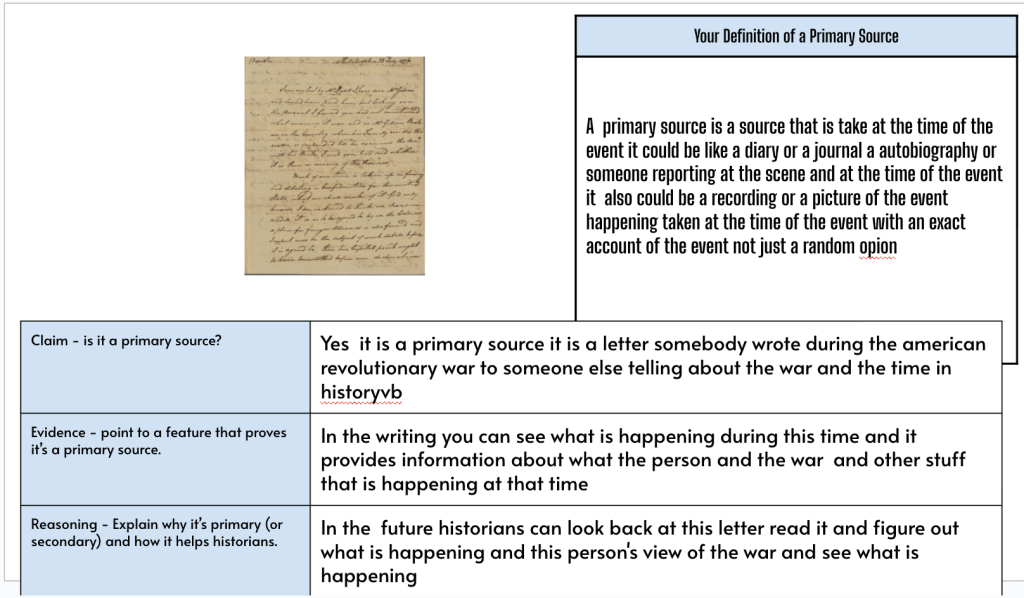

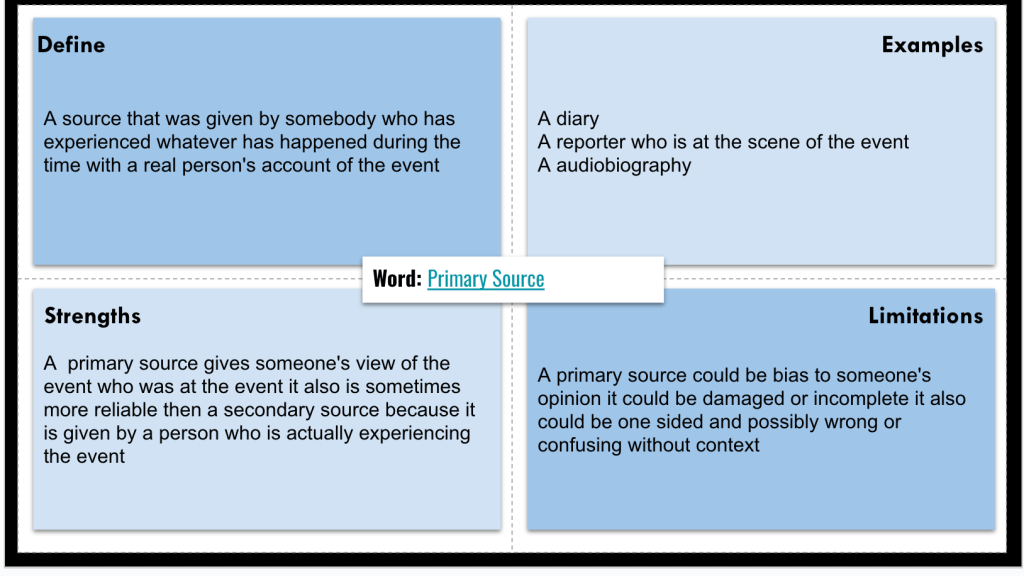

We kicked off our new theme this week: Sources and Sourcing. The goal is simple but essential: help students recognize the difference between primary and secondary sources and begin applying that understanding.

We started with a Quizizz check in, and the results told me all I needed to know: most students had no clue. That changed my plan immediately. I scrapped my original idea and built a Rack and Stack that gave them multiple reps with the concept.

Here’s how it broke down:

- Thin Slide – Students picked a source, labeled it primary or secondary, and shared with a partner. A quick, low-stakes way to get them thinking.

- Frayers – Two total: one for primary, one for secondary. Students added definitions, examples, and nonexamples to deepen their understanding.

- Word Wall – They sorted sources on their own. No scaffolds, no hints. Just a test of what they knew after the Frayers.

- Thick Slide – The application task: If you were researching the American Revolution, what primary source could you use? Students added a picture, used their Frayer definition, and proved they found a true primary source with claim, evidence, and reasoning.

By the end, students weren’t just identifying sources; they were already starting to source them in their writing. That’s the kind of win that makes me feel good about slowing down, scaling back, and laying a strong foundation for what’s coming next.

Tuesday – Digging into Historical Thinking Skills

Tuesday’s focus was on the four historical thinking skills we’ll be leaning on all year: sourcing, contextualizing, corroborating, and close reading. I built a Quizizz Fast and Curious that mixed straight definitions with application-style questions. The first run was rough, class averages came in at 39%, 32%, 38%, 40%, and 52%. What fascinates me is how consistent those numbers always are across classes when students haven’t actually been taught the content yet. It shows me we’re all starting from the same baseline.

From there, I introduced notes on the four terms. To make it stick, I had students complete a Sketch & Tell-o for each drawing a quick sketch to capture the meaning and writing a one-sentence explanation. But I didn’t want it to just stay on paper. As we worked through the notes, I kept tying it back to Monday’s lesson.

I asked a student to look around the room and pick a primary source if they wanted to learn more about me. Some chose the student letters on my wall, others pointed to my Teacher of the Year plaque, and a few grabbed onto classroom photos. With each object, we practiced:

- Sourcing – Who created it? When? Why?

- Contextualizing – What was happening at the time it was made?

- Corroborating – What other source in the room could support or challenge it?

For example, if a student chose my Teacher of the Year plaque, they often paired it with one of the letters from students that helped me earn it. That connection helped them see how sources work together to tell a fuller story.

We wrapped by running the Quizizz again. This time the class averages jumped to 47%, 58%, 59%, 48%, and 74%. It wasn’t perfect, but the growth was clear. Students saw the payoff of practice, and it gave us a strong foundation to keep building on the rest of the week.

Wednesday – Practicing Skills with the Lunchroom Fight

By midweek, I wanted a low-cognitive way for students to actually practice the historical thinking skills we had been building. The Lunchroom Fight 2 activity from the Digital Inquiry Group was the perfect fit.

In years past, I’ve never found this activity to be all that engaging. But this group is different. Being in a small private school, my students know each other well and have strong rapport. They listen to one another. They actually discuss instead of talking over one another.

We started class with another Quizizz for retrieval. Then we jumped into the Lunchroom Fight. A couple of students even asked, “When are we going to learn history?” They were eager to dive into content, but I wanted them to see how skills work in practice.

Students paired up, read through the eyewitness statements, and organized the information. The conversations were good: who seemed reliable, who didn’t, and what evidence actually held up. The end goal was a simple Claim-Evidence-Reasoning:

- Claim – Who was at fault for the fight?

- Evidence – Which statements supported that claim?

- Reasoning – Why does that evidence matter for deciding suspension?

What impressed me most was the independence. Some students even took their papers down the hall into the common area to work, and I could trust them to get it done. That’s a gift as a teacher—watching students take ownership of the task, collaborate authentically, and actually enjoy practicing skills.

Thursday – Jumping Into History

Thursday was the first day we really shifted from skill-building to applying those skills with actual history. We started class the same way, with a Quizizz Fast and Curious. The averages told the story: 86%, 81%, 44%, 80%, and 88%. The growth was there, and the quick retrieval gave students confidence heading into the lesson.

From there, we moved into a sourcing activity from the Digital Inquiry Group. The prompt was tied to a famous image: Is this painting of the First Thanksgiving a reliable source to understand the relationship between the Wampanoags and the Pilgrims? Most students confidently said yes. But the reveal that the painting was created 311 years after the actual event surprised them. Once they thought about it, they understood why it was not reliable. That “aha” moment was powerful.

We used that as a bridge into another historical painting, Percy Moran’s Molly Pitcher Firing Cannon at the Battle of Monmouth (1911). Students leaned on the four skills of sourcing, contextualizing, corroborating, and lateral reading to break down the image. The conversations were sharp. They questioned the reliability, discussed how memory and myth can reshape events, and pulled connections to what we had been practicing all week.

We closed with a writing task:

Prompt: After analyzing Percy Moran’s painting Molly Pitcher Firing Cannon at the Battle of Monmouth (1911) using sourcing, contextualization, corroboration, and lateral reading, write a short response using the Claim–Evidence–Reasoning framework.

Instead of collecting responses on paper, I had students type their CERs into ShortAnswer. Then we ran a Battle Royale. Students voted responses up and down, debated which claims were strongest, and saw firsthand what made evidence and reasoning effective. It was a blast. The energy in the room was exactly what I want, with students engaged, competitive, and thinking critically about history.

Friday – Exploring Bias

Friday’s focus was on bias, which is always a tricky concept to teach middle schoolers. I adapted a lesson from Mr. Roughton and shaped it for my classes. We began with one final Quizizz Fast and Curious, and the results were strong: 86%, 80%, 83%, 83%, and 91%. That showed me they were ready for a challenge.

To introduce bias, I showed a recut trailer of Finding Nemo. Someone had spliced together lines and clips from the movie but paired it with horror film music. Every student had seen Finding Nemo, so they were shocked and confused by what they saw. That was the hook. I explained that nothing in the trailer was a lie, but the way the clips were cut and the music that was added changed the perspective completely. Bias works the same way. It is not always about telling falsehoods. Sometimes it is about presenting information in a way that leaves out parts of the story or makes it feel different than it really is. That clicked for them.

Next, we moved into a CyberSandwich on John Brown. I gave each student an article that ChatGPT had created for me. One came from the perspective of a northerner, the other from the perspective of a southerner. The students did not know that they were reading different accounts. Each article contained the same facts but used loaded language to create very different impressions. To scaffold, I gave them guiding questions:

- List as many words or phrases as you can find that make John Brown look positive.

- List as many words or phrases as you can find that make John Brown look negative.

- Sourcing – Who might have written this account? How could that influence the way John Brown is described?

- Contextualization – What was happening in the United States in the 1850s that might explain why people described John Brown this way?

- Corroboration – Do you think this reading gives you enough information to make a good decision about who John Brown really was? Why or why not?

- Based on what you read, who was John Brown?

As students worked, most had no idea they were reading different articles. In one class, someone raised their hand and said, “I can’t find anything positive.” Another student responded, “What? How can you not?” That sparked immediate comparisons and conversations. The realization that they had been given different accounts blew their minds. They begged to read the other version. That was the moment bias became real.

We closed with a CER: Was John Brown a hero or a villain? Students pulled from their notes, their comparisons, and their discussions to make a claim, back it with evidence, and explain their reasoning. The engagement was high, the conversations were thoughtful, and the lesson tied right back to the Finding Nemo trailer. It was the perfect way to end the week.