This week was all about variety, structure, and student voice—anchored by a solid lineup of EduProtocols. I leaned on Fast & Curious for foundational vocab, layered in Annotate & Tell to break down complex readings, used Number Mania to push students toward using evidence, and wrapped lessons with Short Answer and Nacho Paragraphs to bring writing and thinking together. We even threw in some creative fun with Thin Slides, Craft-a-Cola, and a few MagicSchool tools to help students prompt and produce in more engaging ways. It wasn’t just about covering content—it was about designing experiences that stuck.

Monday – Industrialization Rack and Stack

Tuesday – Inventions Rack and Stack

Wednesday – Lowell Mills Rack and Stack

Thursday – Labor Unions Reading

Monday

We kicked off the week with a lesson on industrialization and how it changed the northern states—and I tried a Rack and Stack combo I was really happy with. It wasn’t flashy, but it had purpose at every step. Each EduProtocol built on the last, and everything came back to our guiding question: How did industrialization change the northern states?

Fast and Curious: Vocab First

We opened with a Gimkit Fast and Curious using vocabulary that kids were likely to struggle with—rivers, factories, mass production, loom, spinning, sewing machine. A lot of times I assume kids know basic words, but they don’t. After the first round, I gave feedback and cleared up confusion around things like loom and mass production. Then we ran it again. By the second round, scores had gone way up—evidence that repetition and feedback work.

Thin Slide: Why the North?

Next, I used a Thin Slide variation I learned from Justin Unruh. Students were asked to answer the question: Why did industrialization occur more in the North? using the keywords rivers and factories. They found or created an image and gave a one-sentence explanation. They had 8 minutes total—then they shared live, 8 seconds per student. This was a great way to preview the bigger concepts without overwhelming them.

Annotate and Tell: 3 Phases of Industrialization

We moved on to an Annotate and Tell with a short reading on the three phases of industrialization. Students highlighted the three phases in yellow and highlighted any inventions or machines in blue. The reading wasn’t long, but it was packed with information. I asked them two big questions to process:

- What are the three phases of industrialization, and how did each one change the way goods were made?

- How did machines like looms and sewing machines change the way people worked in factories?

Kids worked in partners to discuss and respond, and I was impressed with how well they broke it down.

Sketch & Tell Comic Edition: Visualizing the Phases

After the reading, I had students create a 3-frame comic using the Sketch and Tell Comic Edition to show how the three phases changed life and work. I got this idea from Justin Unruh again, and it’s become one of my favorite go-to protocols for visual processing. Instead of just retelling, students visualized each stage and added one sentence of explanation. This helped students slow down and make sense of how the shift happened over time—from breaking down tasks, to building factories, to powering machines.

Padlet Thin Slide: Bringing It Back to the Big Question

To wrap it up, we returned to our original question—How did industrialization change the northern states?—with a final Thin Slide posted on Padlet. I gave them 5 minutes to respond using what they had just learned, and they had to include at least one piece of evidence from the comic or Annotate and Tell. This helped me see who really got it and who might need more support.

It was a solid Rack and Stack, and I loved how each piece of the lesson connected. The goal wasn’t to cover everything—it was to build background, layer the concepts, and give students multiple ways to process. That’s what makes EduProtocols work.

Tuesday

I’ll be honest—Monday didn’t go how I hoped. The engagement across all my classes hovered around 25%, and that’s not something I’m used to. It frustrated me, and it forced me to take a step back. I told the students on Tuesday that I intentionally design lessons to build on familiar ideas. I don’t want them to feel overwhelmed—but I also don’t want them to zone out.

So I had to flip the script.

Fast and Curious: Quizizz Rebound

We opened class with a Fast and Curious on Quizizz using questions tied directly to industrialization in the North. This wasn’t just vocab—it was context-based. Words like steamboat, reaper, plow, and telegraph were sprinkled in. I noticed how often students missed even basic terms. Sometimes we assume students know what words like “petition” or “shift” mean, but they don’t. The data from Quizizz told me exactly where to go next.

Frayer Models With a Twist

We jumped into a Frayer activity using the textbook reading on four major inventions of the 1800s: the steamboat, the mechanical reaper, the steel plow, and the telegraph. But this wasn’t just a regular Frayer. I added some chaos—two dice rolls per invention. The first determined how many bullet points they had to write, the second decided how many words each bullet needed. This created structure, accountability, and a layer of challenge.

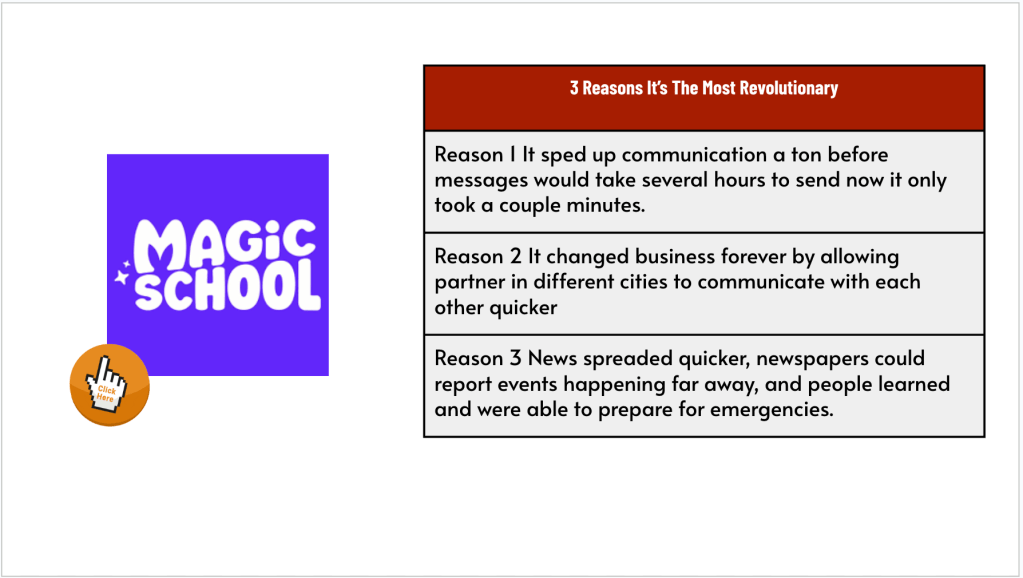

Chatbot Collaboration: Magic School AI

Next, I had students select the invention they thought was the most revolutionary. Using Magic School’s chatbot, they prompted the AI to speak as if it were that invention. They asked follow-up questions and gathered more support. This was one of my favorite moments—watching students debate themselves through the screen, pushing AI for deeper evidence.

Short Answer: Writing With a Purpose

We wrapped up with a Quick Write on ShortAnswer. This tool has been a game-changer. I selected two rubric elements: clear use of evidence and strong conventions. The AI gave instant feedback and categorized responses as beginner, intermediate, or advanced. Then it added up class scores to see if we hit our class goal. Three of my four classes crushed it.

But the best part? I disabled copy and paste. The words they wrote were their own.

I told them if they hit the class goal, I’d wipe away their Monday mess. They locked in and crushed it. Students were writing. For real. Because the task had structure, purpose, and a chance to improve.

Wednesday

Today’s lesson was all about one sentence:

“The Lowell Mill Girls had an extraordinary opportunity.”

That was it. That was the line that carried us through the whole class. My goal? Get students to keep circling back to that claim—support it, refute it, challenge it, reframe it. Think about it, talk about it, write about it.

I used a Rack and Stack of familiar EduProtocols, but I tried to tweak the flow a little to hit a rhythm. And honestly, it worked.

Fast and Curious: Start with What They Don’t Know

We kicked things off with a Fast and Curious using Gimkit. Vocabulary was pulled straight from the lesson:

boardinghouse, wage, petition, strike, shift.

You’d be surprised how many students don’t know what a “shift” is. Or “petition.” Or “boardinghouse.” After one 3-minute round and some direct feedback, we ran it again—and it made a big difference. The repetition and immediate correction helped lock it in. And it gave us a foundation to move forward.

EdPuzzle + Thin Slide = Instant Reflection

Next, we watched a 4-minute EdPuzzle about the Lowell Mill Girls. I embedded a Thin Slide right in the middle and brought the original claim back:

“Did this video support that statement or not?”

Some said yes—they got paid, they had housing. Others said no—the pay was awful, the work was grueling, and the living conditions weren’t great either. It was cool to see students start forming opinions and backing them up with specific parts of the video. The Thin Slide forced them to pick a side and start thinking critically before we even got to the meat of the lesson.

Number Mania: Let the Numbers Talk

Then we moved into Number Mania. Originally, I had six stations planned, each with a short reading—some primary, some secondary. But after thinking about cognitive load (and remembering that part in Blake Harvard’s book), I cut it down to four. Best decision I made all week.

At each station, students had to pick a number from the reading that could be used to refute the original statement. Of course, we had to stop and break down what “refute” actually meant—another word straight off the state test that most students didn’t know.

To make it even more fun (and to fight copy-paste laziness), I rolled dice. The first die told them how many words they had to use. That forced them to be intentional and selective with their evidence. Every station, every round, they got better at it.

Short Answer x Nacho Paragraph: Final Hit

To bring it all together, we used the Nacho Paragraph protocol inside Short Answer. I told students to copy and paste the original statement and revise it. Fix it. Refute it. Use the numbers and facts they just found in the Number Mania.

We ran it Battle Royale style. They saw each other’s answers. They compared. They got feedback. And most importantly, they thought.

They were engaged. They weren’t writing because I told them to. They were writing because they had something to say.

Thursday

After a deep dive into the Lowell Mill Girls earlier in the week, I wanted to extend the conversation—this time with a focus on labor unions and how the legacy of early industrial labor still echoes today.

We kicked things off with a short, one-page reading about the Lowell Mill Girls and labor unions. The reading did a solid job tying the historical context to modern labor movements. Students answered five questions to check comprehension and pull key ideas.

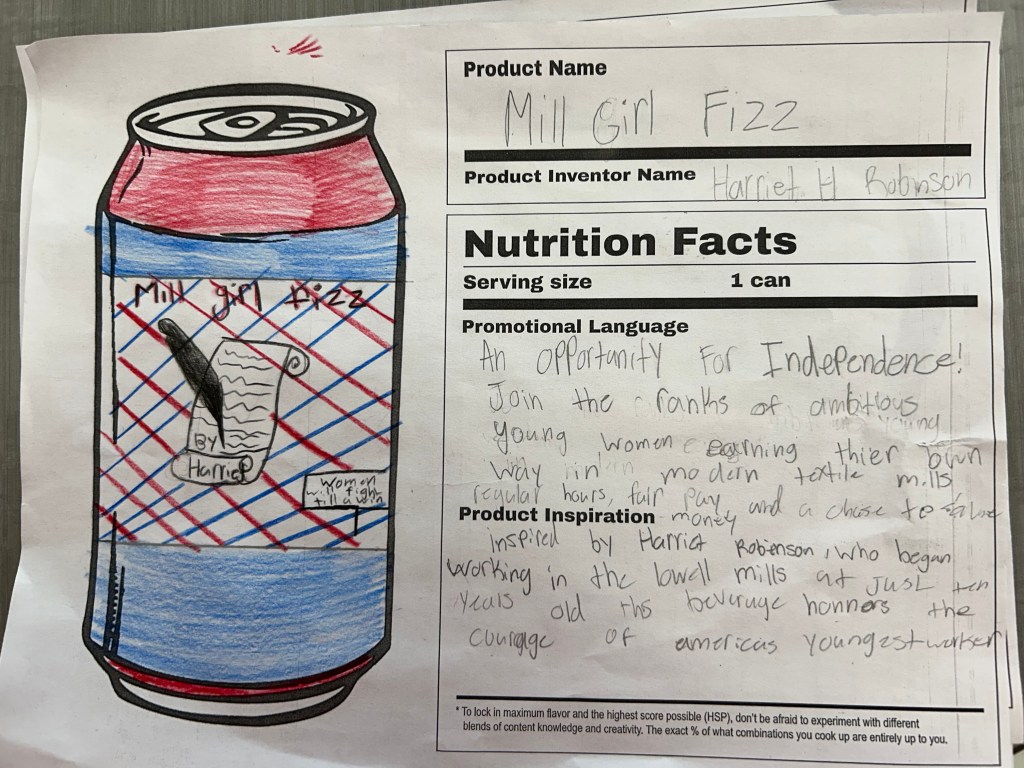

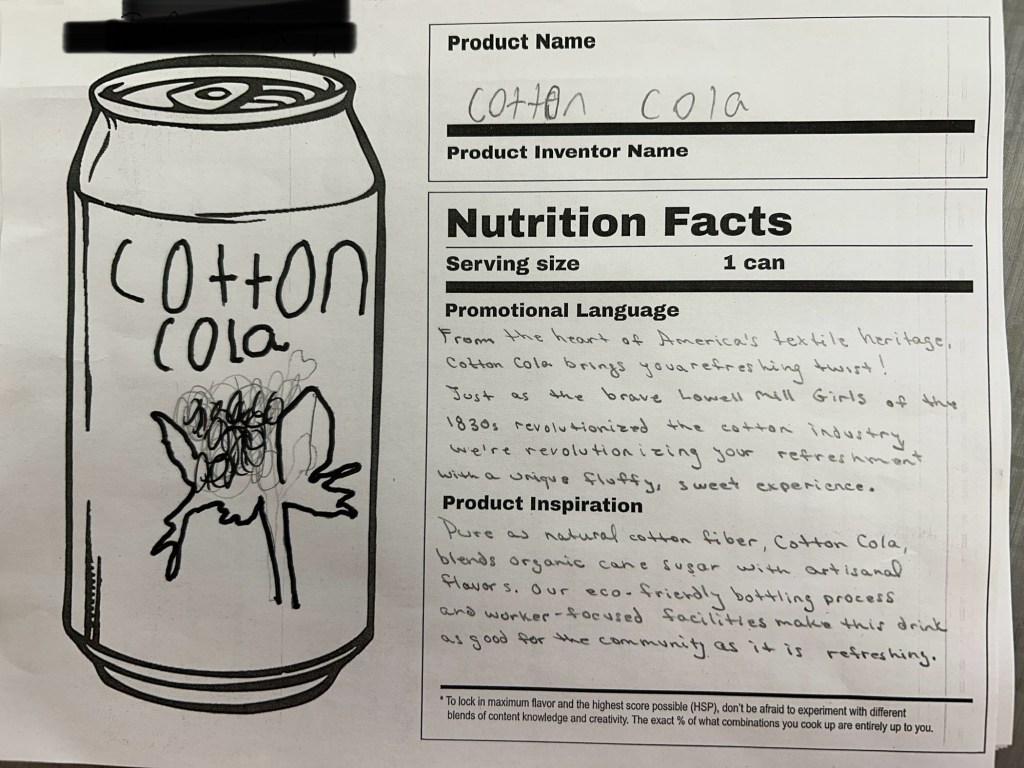

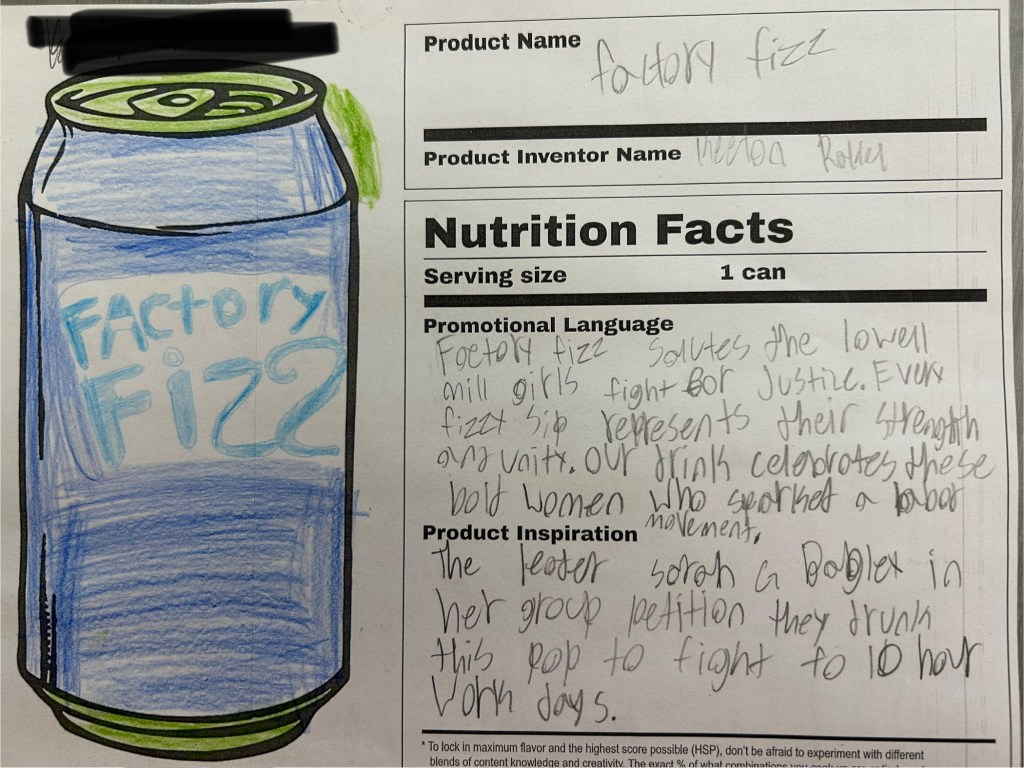

Then we pivoted into something a little more creative: a template from EMC² Learning called Craft-a-Cola.

Here’s the setup:

Students had to design a pop can inspired by the Lowell Mill Girls and the rise of labor unions. Their can needed:

- A creative soda name

- A slogan or promotional phrase

- A short write-up explaining the historical inspiration behind their product

This was a fun twist, but I knew right away some students would struggle with generating ideas. So I built a Magic School classroom with a custom idea generator chatbot. Students used it to brainstorm potential pop names and promotional language.

Here’s what I learned: 8th graders don’t always know how to prompt clearly. At first, a lot of the results were pretty off—or the bot responded with something like “I can’t do that, but here’s a suggestion…” It turned into an unexpected mini-lesson on how to write better prompts.

We took a few minutes to break down what makes a good prompt, rewrote some together, and suddenly the ideas started flowing.

What I liked most about today’s lesson:

- It gave students a new way to process content they’ve been learning about all week

- It tied creative thinking to historical understanding

- It sneakily taught them better AI prompting skills without me planning for that to happen

Some of their designs were pretty awesome.

A few were flat-out hilarious.

But all of them reflected some understanding of how labor unions began and why they mattered—proof that even a pop can can tell a powerful story.