Last week was all about layering EduProtocols to tackle complex historical topics in engaging, meaningful ways. From political parties to the War of 1812, we used Thin Slides, Archetype Four Square, Frayer Models, Progressive Sketch and Tell, Map and Tell, and Class Companion to help students synthesize, visualize, and apply their knowledge. Instead of passively reading from the textbook, students were analyzing, predicting, debating, sketching, and writing, making these historical moments stick. Here’s a breakdown of how EduProtocols transformed our week and why they worked.

Monday – Political Parties Rack and Stack

Tuesday – John Adams

Wednesday – Marbury vs. Madison

Thursday – Louisiana Purchase

Friday – War of 1812

Monday: The Birth of Political Parties and the Election of 1796

If I had my way, I’d start the Early Republic unit with political parties and go deep. I’d have students analyze the decisions of early presidents through the lens of Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, helping them connect ideology to action. But instead, I’m following the textbook—a textbook that does a poor job of explaining how early party beliefs shaped America’s foreign and domestic policies and ultimately led to the War of 1812.

Rather than let the textbook dictate a shallow, disconnected lesson, I did what I always do—I adapted, structured, and layered EduProtocols to make political parties click for my students.

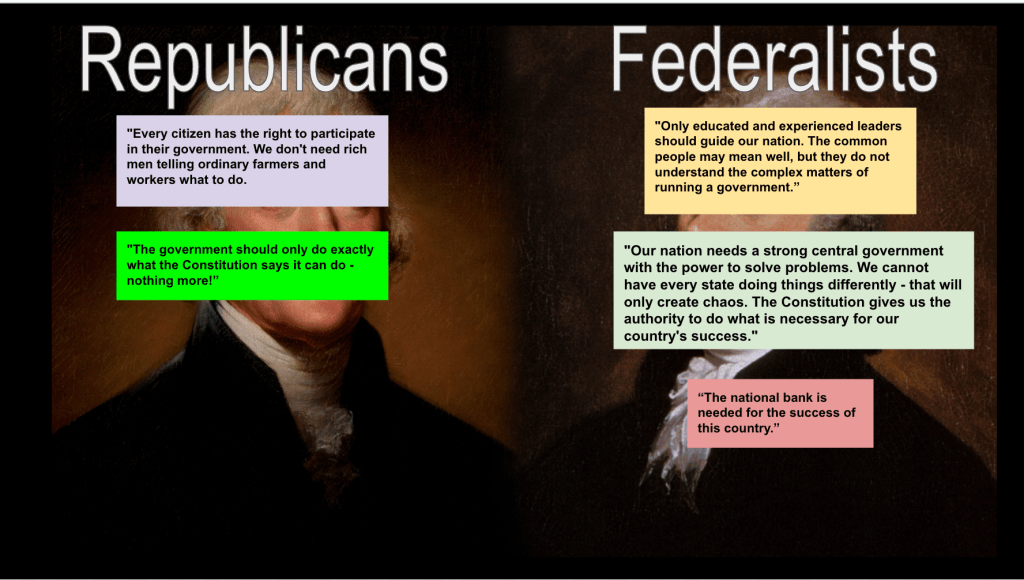

Quick Notes: Laying the Foundation

We started with quick notes to introduce how political parties formed in the 1790s, the key differences between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, and the founding figures behind each party—Alexander Hamilton vs. Thomas Jefferson. These notes were designed to be brief and targeted—just enough to set up the next activity while keeping students engaged.

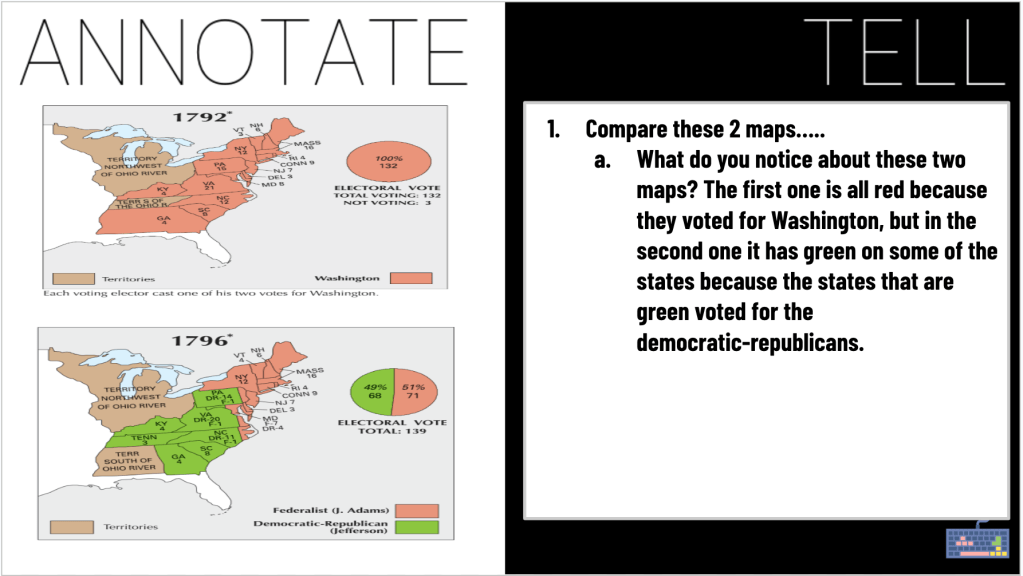

Map and Tell: Visualizing Political Divides

Next, we used a Map and Tell to analyze the elections of 1792 and 1796. Students examined who won the elections (Washington in 1792, Adams in 1796), where each party gained support (Federalists dominated New England, Democratic-Republicans gained strength in the South and West), and how political divisions emerged geographically. This was eye-opening for many students, who could see how early America was already divided in ways that still echo in modern politics.

Annotate and Tell: Organizing Party Beliefs

To make sense of the ideological divide, students used Annotate and Tell to highlight and code their readings. They highlighted Federalist beliefs in blue and Democratic-Republican beliefs in green. By the end, students had color-coded party perspectives on government power, the economy, foreign relations, and constitutional interpretation. This strategy helped students organize and visualize each party’s stance, making it easier to compare and contrast.

Quote Sort: Who Said It?

Now that students had a solid grasp of each party, we moved into a Quote Sort. I gave them statements from historical figures, and they had to drag and drop them under either Federalists or Democratic-Republicans. Examples included:

- “The country should be led by the wealthy and educated.” → Federalists

- “States should have more power than the national government.” → Democratic-Republicans

This activity forced students to think critically and apply their knowledge, reinforcing party beliefs in a hands-on way.

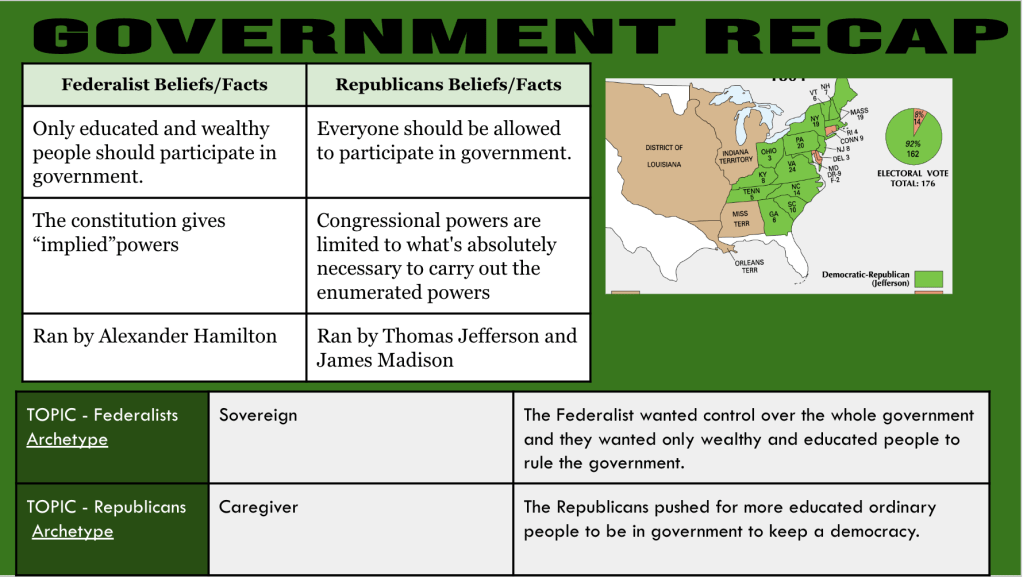

Thick Slide: Bringing It All Together

To synthesize everything, students completed a Thick Slide where they assigned archetypes to Hamilton and Jefferson, compared Federalist vs. Democratic-Republican beliefs, and found images that represented each party’s values. This final layer helped students see patterns, make connections, and process the big picture in a creative, visual way.

Class Companion: Writing on the Election of 1796

To wrap it all up, students used Class Companion to answer: How did disagreements between Hamilton and Jefferson lead to both the creation of political parties AND an unusual outcome in the election of 1796?

Class Companion provided real-time feedback, pushing students to refine their writing. The AI-driven scoring gave them a clear sense of what worked—and what needed improvement. Since they had multiple attempts, students were motivated to revise and improve their responses in real time. Some students got competitive, trying to perfect their answers on their third attempt. Seeing them actually excited about revising their writing was a huge win.

Why This Works

- Map and Tell gives students a visual connection to political divisions.

- Annotate and Tell helps students organize party beliefs clearly.

- Quote Sort turns ideological differences into an interactive challenge.

- Thick Slides encourage students to synthesize information creatively.

- Class Companion makes writing engaging, immediate, and iterative.

Students analyzed, compared, discussed, and created. This layered approach made early political parties meaningful, memorable, and real.

Tuesday: John Adams

I’ve been using the textbook, but I’m running out of time. The reality of trying to fit everything into the unit assessment timeline has me teaching to a test instead of focusing on deep learning and real understanding. This is not education. I feel like a robot, checking boxes rather than tailoring lessons to what my students actually need. But, despite the constraints, I found ways to layer in engagement and critical thinking while still covering the required content.

Quick Notes: Laying the Foundation

I started class with quick notes to introduce:

- Background on John Adams—his role in the revolution, his Federalist views, and his leadership style.

- Foreign policy challenges—especially rising tensions with France.

- The XYZ Affair—what happened and how it impacted U.S.-French relations.

- The Alien and Sedition Acts—why Adams passed them and how they divided the nation.

These notes set the stage, ensuring students had context before diving into deeper analysis.

Fast and Curious Gimkit: Reinforcing Key Ideas

Next, we ran a Gimkit Fast and Curious with questions on John Adams and political parties. Students played for three minutes, I provided instant feedback, and we played again. This quick retrieval practice helped reinforce key concepts, ensuring they recognized important terms and events before moving forward.

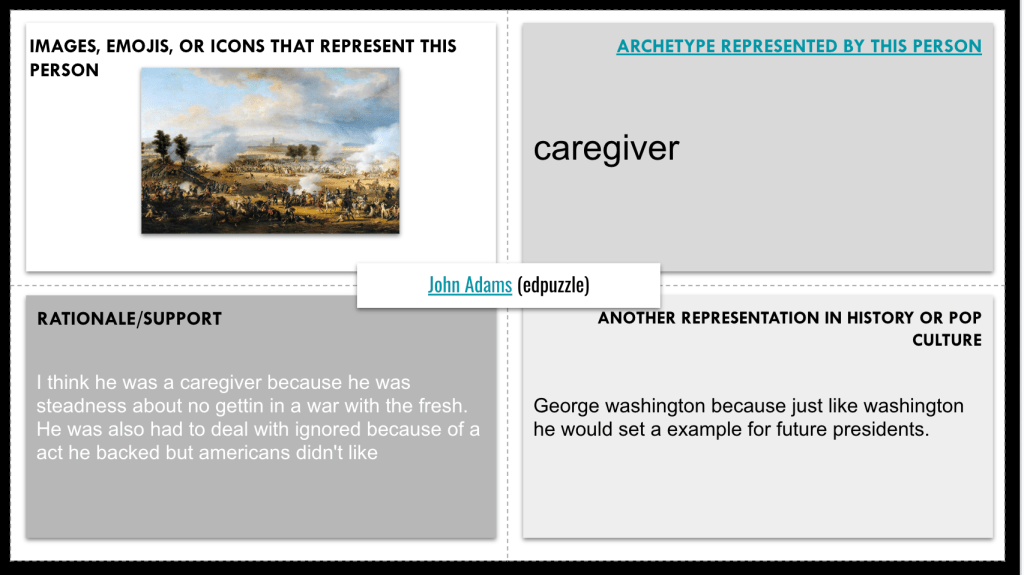

Archetype Four Square: Understanding John Adams

To push students toward higher-order thinking, we used an Archetype Four Square activity.

Students watched an EdPuzzle on John Adams while thinking about which archetype best fit him. Was he:

- A Protector, trying to defend the country from French interference?

- A Ruler, who prioritized law and order with the Alien and Sedition Acts?

- A Visionary, thinking ahead for what was best for the country long-term?

They had to choose an archetype, justify their reasoning, and discuss with a partner. This helped them see Adams as more than just another name in the textbook—they began analyzing his motivations and leadership style.

Sketch and Tell Connect: Breaking Down the Issues

We then moved into a Sketch and Tell Connect, where students answered four guided questions pulled from the textbook’s guided reading section. The goal was for them to process and organize what they had learned.

To push them further, I used a Somebody Wanted But So Then (SWBST) structure for the sketches:

- Somebody (John Adams or France)

- Wanted (to protect the U.S., avoid war, maintain Federalist power, etc.)

- But (tensions with France, backlash to Alien and Sedition Acts, etc.)

- So (the government took action)

- Then (the impact on the country and his presidency)

This was challenging for them. Synthesizing content like this is a higher-order skill, and many struggled to condense complex events into simple cause-and-effect relationships. But that’s the whole point—we’ll keep practicing.

Class Companion: Writing on Adams’ Presidency

To wrap up, students used Class Companion to summarize the major problems Adams faced as president. They had to explain the XYZ Affair, the Alien and Sedition Acts, his dealings with France, and the Federalist Party split.

The AI-powered feedback helped students clarify their writing, refine their ideas, and strengthen their arguments. Some improved their responses after multiple attempts, realizing where they needed stronger evidence and explanations. Seeing students revise and rethink their work in real time was a win.

Why This Works

- Fast and Curious Gimkit reinforced content through repetition and quick retrieval.

- Archetype Four Square encouraged critical thinking about Adams’ leadership style.

- Sketch and Tell Connect with SWBST pushed students to synthesize information visually and see the cause-and-effect relationships in history.

- Class Companion writing gave students instant feedback, helping them improve their ability to explain and analyze historical events.

Even though I felt trapped by the textbook and assessment timeline, I made sure students weren’t just memorizing—they were thinking, discussing, and applying. That’s what makes learning stick.

Wednesday: Marbury v. Madison

One of the essay questions on the textbook unit assessment asks students to write about Marbury v. Madison. So, as I continue teaching to a test (insert sarcasm), I put together a lesson solely focused on the case. What’s funny is that the pre-assessment for the unit didn’t include a single question on Marbury v. Madison, yet somehow, students are expected to write an essay about it at the end of the unit. The textbook dedicates two paragraphs to explaining the case—two paragraphs—and assumes that’s enough for middle schoolers to write an in-depth response.

Luckily, I already had a lesson from last year that actually helps students understand this case in a meaningful way. It’s structured, layered, and built for comprehension rather than memorization.

Quick Notes: The Supreme Court Before Marbury v. Madison

We started with quick notes on the weaknesses of the Supreme Court before this landmark case. The Court was not seen as a powerful branch, and many people questioned its authority. Marbury v. Madison changed that by firmly establishing the Court’s power of judicial review—the ability to declare laws unconstitutional.

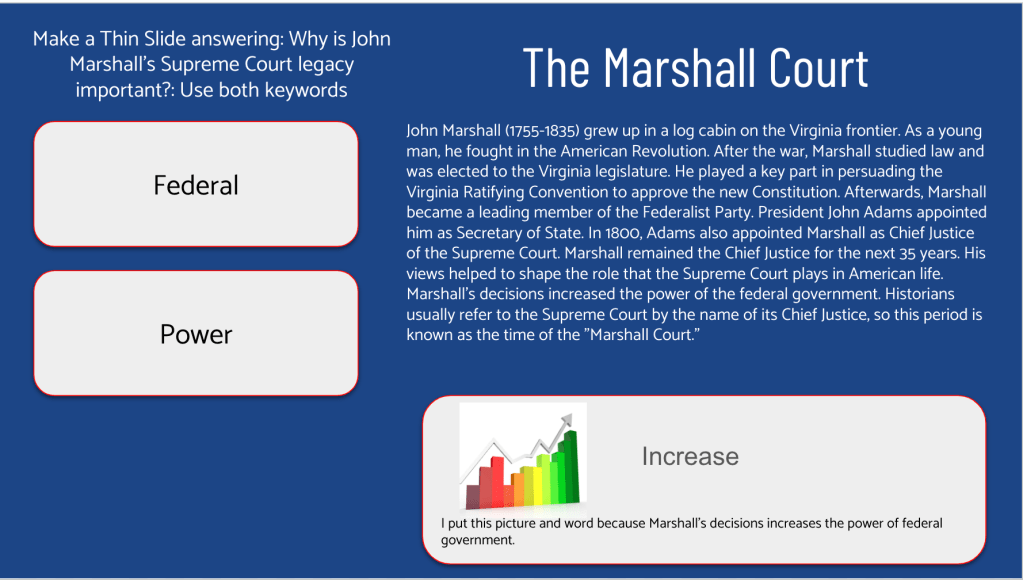

Thin Slide: John Marshall’s Supreme Court Legacy

To introduce John Marshall, students completed a Thin Slide answering:

Why is John Marshall’s Supreme Court legacy important?

Students added one word and one picture to represent his impact and responded to the question. This quick, low-stakes activity gave them an opportunity to process key ideas visually before we dove deeper.

Frayer Models: Breaking Down Key Concepts

Next, students built background knowledge using two Frayer models—one for judicial review and one for writ of mandamus.

For each concept, they:

- Defined it in their own words.

- Paraphrased a Google definition (to compare with their explanation).

- Came up with three connecting words to reinforce meaning.

- Illustrated the concept using a GIF or meme.

This structured approach helped students grasp difficult legal terms and connect them to real-world applications.

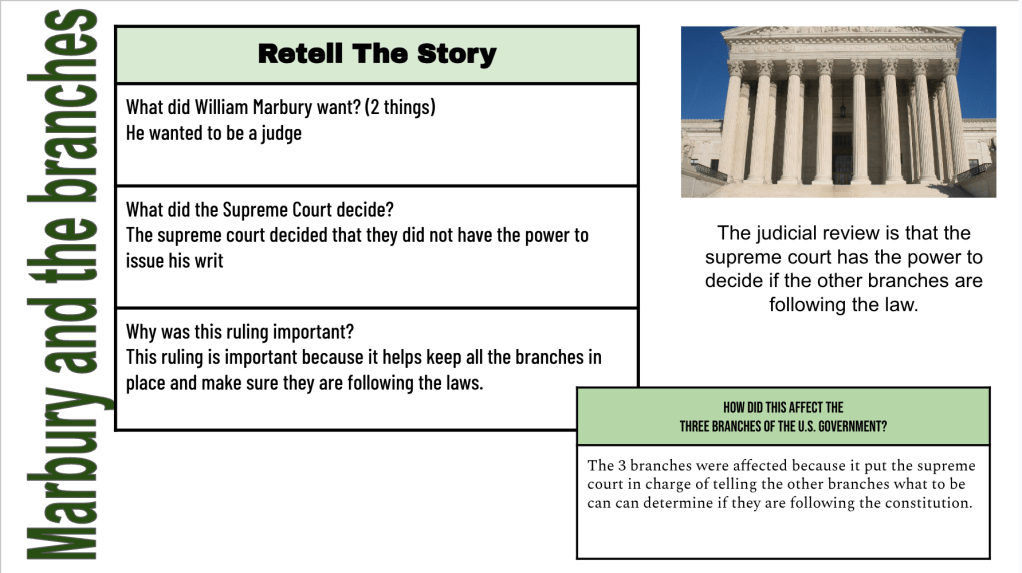

Reading the Case: Making It 8th-Grade Friendly

The textbook’s two-paragraph explanation wasn’t enough, so I adapted an iCivics reading to simplify the language while maintaining accuracy.

Students read about:

- What William Marbury wanted (his commission as a judge).

- What the Supreme Court decided (they couldn’t force Madison to deliver the commission).

- Why the ruling was important (it established judicial review).

Students completed a Thick Slide to organize their learning, breaking the case into cause, decision, and impact—a direct alignment with the essay question they’ll face on the unit test.

Annotate and Tell: Marshall’s Ruling

We then moved to primary source analysis. Students read excerpts from John Marshall’s ruling and used Annotate and Tell to highlight key ideas.

As they read, they:

- Highlighted Marshall’s views on who should have the final say in interpreting the Constitution.

- Answered: What does Marshall say is the Supreme Court’s job and responsibility? Why is this important to his argument?

This activity reinforced the central argument of judicial review—that the Supreme Court’s job is to interpret the Constitution and override laws that contradict it.

Gimkit Fast and Curious: Wrapping It Up

To cement understanding, we ended class with a Gimkit Fast and Curious on Marbury v. Madison. After one round, I gave feedback, and we played again. By the second round, students were improving their recall and accuracy, showing that the layered approach to this lesson worked.

Why This Works

- Thin Slides helped students preview the key figure (John Marshall) in a quick, engaging way.

- Frayer Models broke down complex legal concepts into manageable, student-friendly chunks.

- A carefully adapted reading ensured that all students could access the information—not just the ones who can decipher legal jargon.

- Thick Slides allowed students to process the case visually and organize their learning for the upcoming essay.

- Annotate and Tell built close reading skills and helped students engage with Marshall’s ruling in a meaningful way.

- Gimkit Fast and Curious reinforced content through repetition and retrieval practice, strengthening student recall.

I made sure students actually understood Marbury v. Madison instead of just skimming two textbook paragraphs and hoping for the best. That’s why this approach works.

Thursday: The Louisiana Purchase

The textbook’s approach to the Louisiana Purchase makes zero sense. It spends an entire chapter on Napoleon, French colonies, and the lead-up to the purchase, yet barely covers what the purchase meant for the U.S. Then, it dedicates multiple pages to Lewis and Clark, even though there isn’t a single question about them on the unit assessment. Meanwhile, Marbury v. Madison gets two textbook paragraphs, but the test expects students to write a full essay on it. Make it make sense.

Instead of wasting time on unnecessary details, I cut straight to the heart of the matter—why the Louisiana Purchase mattered, why Jefferson took the risk, and why Federalists hated it.

Map and Tell: Predicting Motives

We started class with a Map and Tell prediction slide with the following setup:

“The Democratic-Republican President, Thomas Jefferson, had a bold vision for American expansion that led him to create the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, which doubled the size of the United States for just 3 to 4 cents per acre—arguably the greatest real estate deal in history.”

Students then made predictions:

- Why do you think France was willing to sell such a huge territory to the United States?

- Why do you think the Federalists hated this purchase of Louisiana?

This activity got them thinking before diving into the details. It also highlighted misconceptions early so we could clear them up as we went.

EdPuzzle: Understanding Jefferson’s Vision

Next, students watched an EdPuzzle on Thomas Jefferson to ground them in his mindset—his strict interpretation of the Constitution, his agrarian ideals, and his vision for westward expansion.

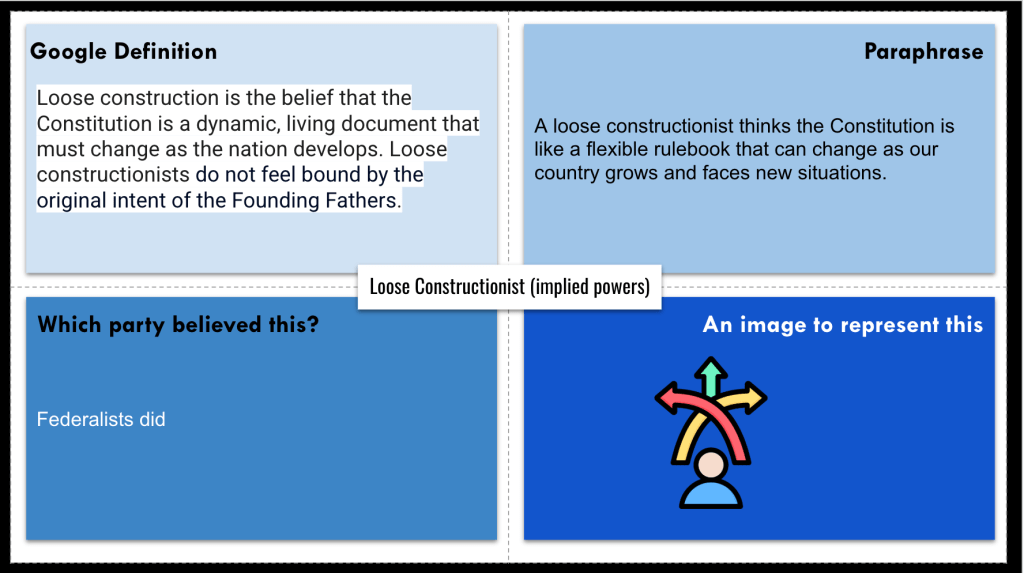

Frayer Models: Strict vs. Loose Constructionists

Since one of the biggest issues with the purchase was that Jefferson had to go against his own beliefs, students completed two Frayer models:

- Strict Constructionist (following the Constitution exactly as written)

- Loose Constructionist (interpreting the Constitution more broadly)

This set up the big debate—how Jefferson, a strict constructionist, justified loosening his interpretation to make the purchase happen.

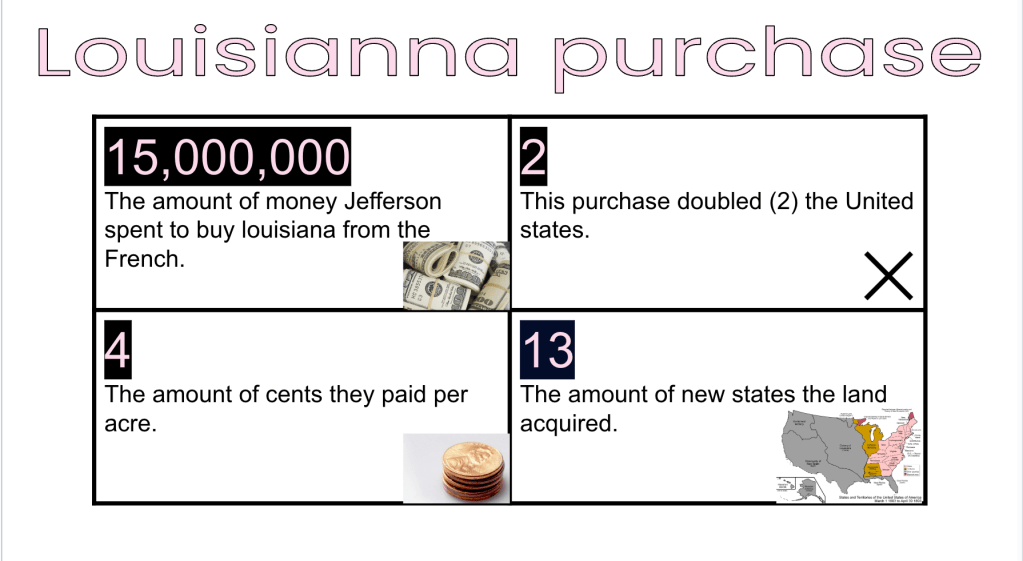

Number Mania: Proving a Statement with Data

Next, we read about the Louisiana Purchase and completed a Number Mania.

For this activity, I gave students a statement they had to prove true using numerical evidence from the text:

“Expanding the country west was a key goal for Jefferson. So even though it went against some of his usual policies, Jefferson made the daring choice to buy all of Louisiana from France.”

Students had to find and highlight numbers that supported this idea, such as:

- The price of the purchase ($15 million, about 3-4 cents per acre)

- The Senate approval vote (26-6 in favor)

- How the purchase doubled the size of the U.S.

Instead of just listing facts, they had to find numbers that connected directly to the bigger argument, reinforcing why the purchase was such a big deal.

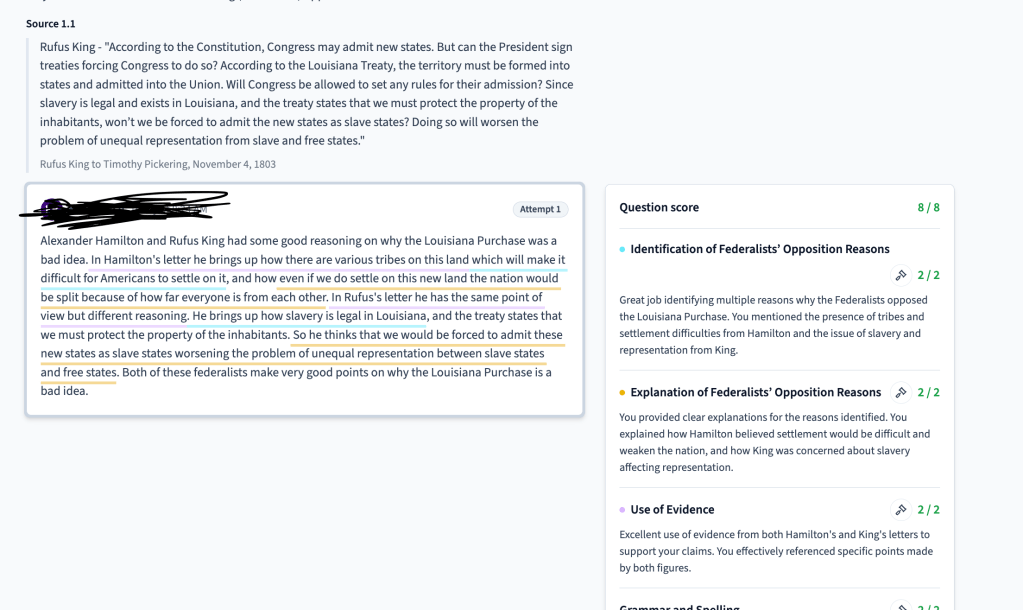

Class Companion: Federalist Opposition to the Purchase

To wrap it up, students went to Class Companion, where they read letters from Alexander Hamilton and Rufus King criticizing the Louisiana Purchase.

Using what they learned from the lesson, they had to write a response explaining why Federalists opposed the purchase. This final step connected everything—Jefferson’s decision, the constitutional debate, the numbers proving its significance, and the political pushback from Federalists.

Why This Works

- Map and Tell made students predict historical motives, encouraging critical thinking before reading.

- EdPuzzle gave students context on Jefferson’s philosophy, making the purchase easier to understand.

- Frayer Models clarified the strict vs. loose interpretation debate, the core constitutional issue of the purchase.

- Number Mania forced students to use evidence-based reasoning, proving why the purchase was so monumental.

- Class Companion writing allowed students to engage with primary sources and articulate historical perspectives.

Even though the textbook wasted pages on unnecessary details, this lesson cut straight to the point, ensuring students understood the key issue—the Louisiana Purchase doubled the U.S., forced Jefferson to change his beliefs, and created major political controversy. That’s what actually matters.

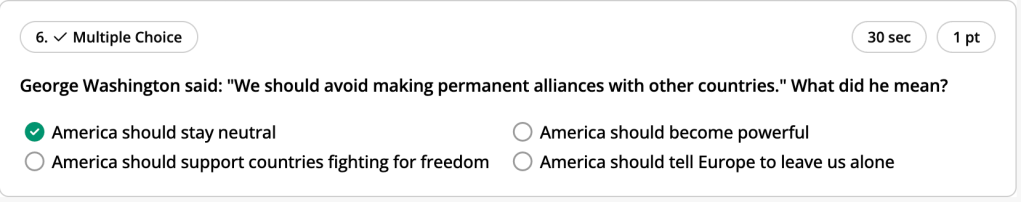

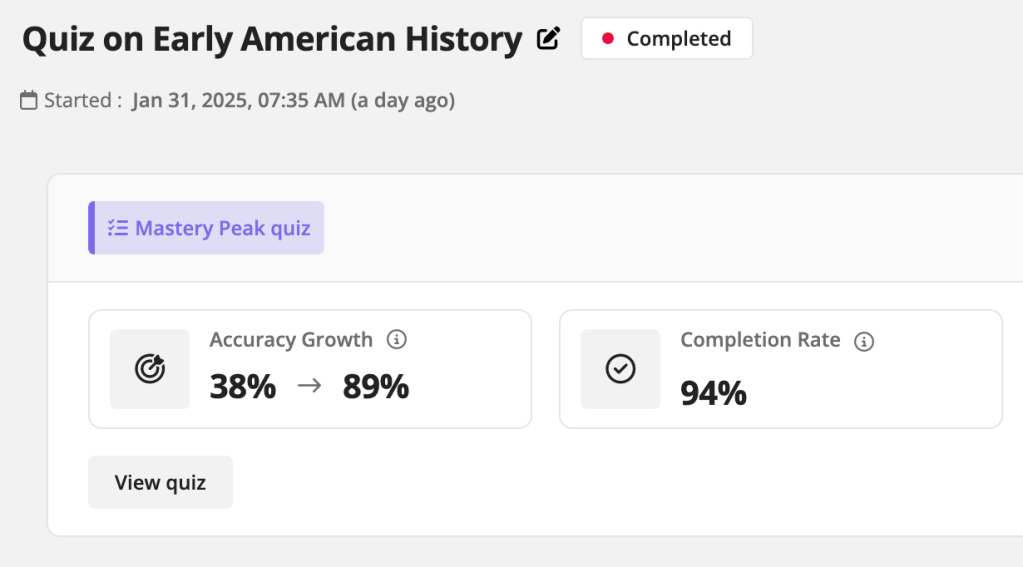

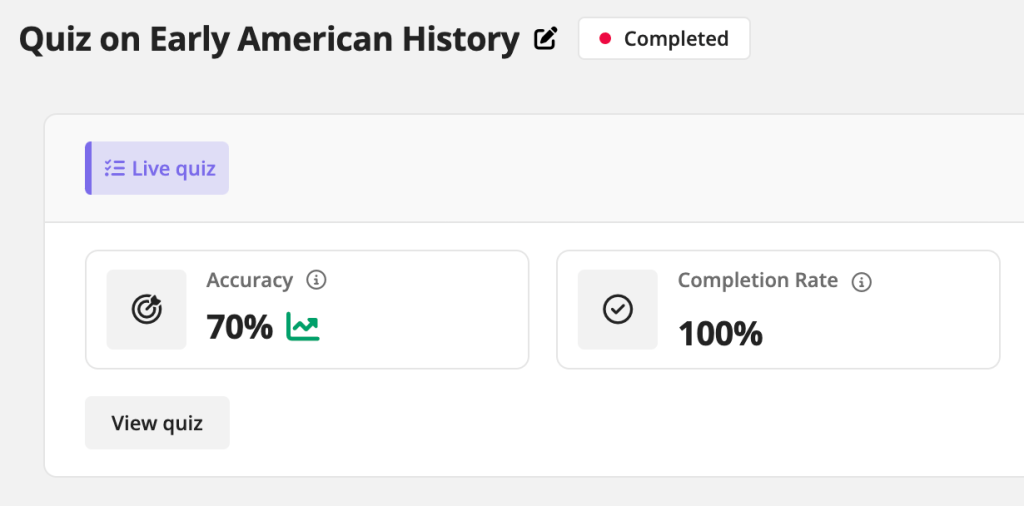

Friday: The War of 1812

Friday began with an experiment—a frustrating but eye-opening one. I took questions directly from the unit test and gave them to 1st and 2nd bell as written. The class averages? 32% and 38%.

Then, I took those same questions, rewrote them in more appropriate vocabulary, and gave them to 5th and 6th bell. The class averages? 70% and 77%.

The results speak for themselves. The kids know the content, but when questions are loaded with unnecessary wording, they struggle—not because they don’t understand history, but because they’re being asked to decode convoluted language.

They are 8th graders, not college students. Why do we keep equating big words with rigor? When I saw 32% and 38%, I felt like a lousy teacher, but I know these kids understand the material. It’s not a comprehension issue—it’s a wording issue.

After that eye-opener, we moved into the War of 1812 with a series of layered activities to connect causes, events, and outcomes.

Quick Notes: The Web of War

We started with quick notes outlining the complex web of decisions that led to the War of 1812.

- The Embargo Act weakened the economy but failed to stop British and French interference.

- Impressment angered Americans as British ships kidnapped U.S. sailors and forced them into service.

- War Hawks in Congress pushed for military action, believing Britain was disrespecting American sovereignty.

- Madison’s Presidency—he inherited the diplomatic failures of Jefferson and ultimately led the country into war.

This framing helped students see the cause-and-effect relationships instead of treating each event as an isolated fact.

Thin Slide: The Embargo Act

Next, students completed a Thin Slide focusing on the Embargo Act. They read a short description and chose:

- One word that represents the act’s impact.

- One image that visually represents the act.

- A quick response to explain their choices.

This forced students to synthesize their thinking quickly and connect the Embargo Act’s impact to the bigger picture.

Archetype Four Square: James Madison’s Leadership

With the Archetype Four Square, students examined James Madison’s leadership and determined which archetype best fit him in the context of the war.

- Was he a Peacemaker, trying to avoid war as long as possible?

- Was he a Reluctant Warrior, forced into action despite hesitations?

- Was he a Commander, embracing war as necessary?

Students had to justify their choices and discuss them with a partner, leading to great conversations about how presidents make wartime decisions.

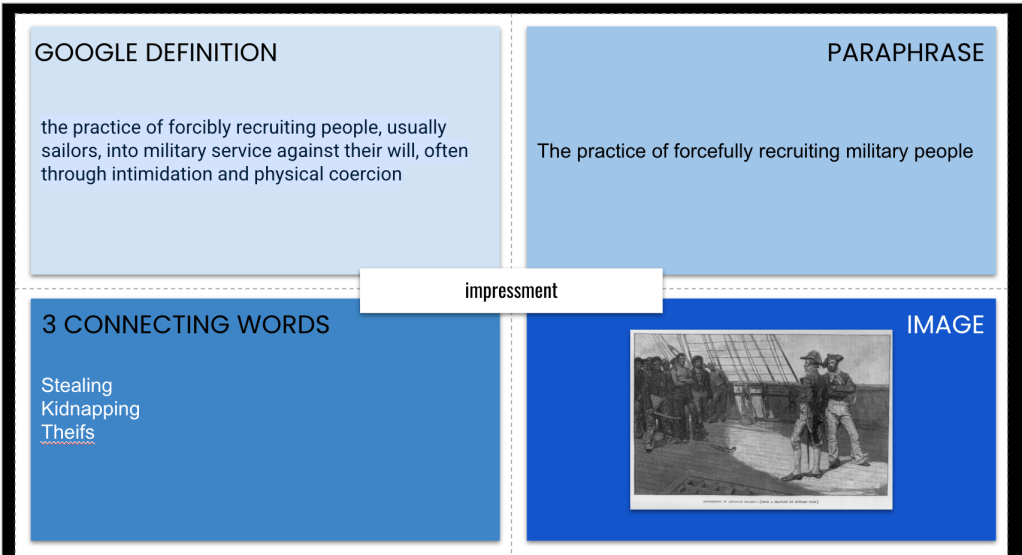

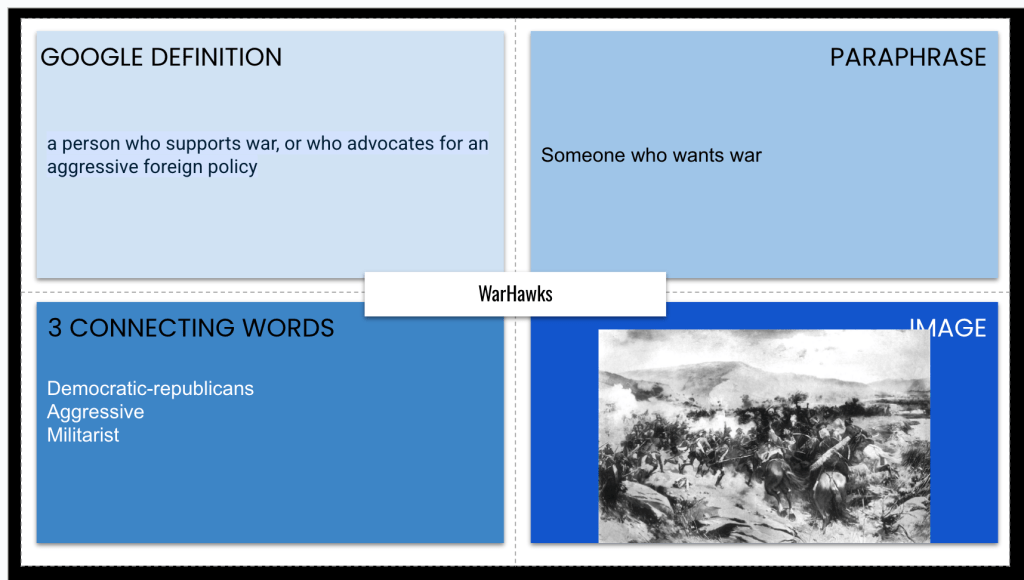

Frayer Models: Impressment and War Hawks

To reinforce key terms, we completed two Frayer Models—one for impressment and one for War Hawks.

For each, students:

- Defined the term in their own words.

- Identified a real-world connection or comparison.

- Illustrated the term with an image, symbol, or icon.

- Listed key facts from the reading to support their understanding.

This helped break down two critical causes of the war into student-friendly explanations.

Progressive Sketch and Tell: The Story of the War

For the main event, we did a Progressive Sketch and Tell to break down the War of 1812 into digestible chunks.

I took the textbook section and had AI split it into five parts.

- Each student received one part at a time.

- They created a sketch and tell comic strip for their section.

- After three minutes, they shared with a partner to explain their visual representation.

- Then, they received the next section and repeated the process.

This step-by-step visual storytelling made a complex war easy to understand. It also helped students see connections between different events rather than treating them as random battles.

Why This Works

- Quick notes created a clear cause-and-effect web instead of just listing events.

- Thin Slides encouraged quick synthesis of key concepts.

- Archetype Four Square made students think critically about Madison’s leadership.

- Frayer Models reinforced essential vocabulary through multiple connections.

- Progressive Sketch and Tell broke the war into digestible chunks, making it memorable and interactive.

Instead of just reading about the War of 1812, students analyzed, created, discussed, and applied what they learned. And that’s what makes the learning stick.