As educators, we are always seeking new ways to make learning meaningful and engaging for our students. This week, my social studies class embarked on a journey to explore the power of stories hidden within artifacts and primary sources. From deciphering the tales behind everyday objects to connecting local history with broader historical themes, our activities aimed to deepen students’ understanding and appreciation of the past. Through a combination of hands-on lessons, creative exercises, and critical thinking challenges, we explored how seemingly simple items can reveal complex narratives about our lives and the world around us. This blog post chronicles our week of discovery, highlighting the strategies, successes, and lessons learned along the way.

Monday – Sources

Tuesday – Sourcing Thick Slide Lesson

Wednesday – 5 Themes of Geography Thin Slide

Thursday – Resource Rumble

Friday – Thick Slide Assessment

Monday

This week, we continued our lesson from Dan Lewer on making sense of artifacts and primary sources, focusing on the stories these sources might tell us. It seemed like the perfect opportunity to begin class with the Town Dump Lesson. I asked the kids, “Does everything have a story?” Initially, they looked puzzled, unsure how to answer. To help them understand, I shared some examples of random objects that might seem meaningless to them but hold stories for me. For instance, I have a globe in my room. When I ask, “Why do I have this globe?” they typically respond, “Because you teach social studies.” While this is true, I explain that the story they don’t know is that it belonged to a colleague of mine who passed away during the middle of the school year. It reminds me of her, which is why I kept it. I then pointed to the student notes on my wall, explaining, “I have these notes because each one tells a story of an impact or time I had with those students.”

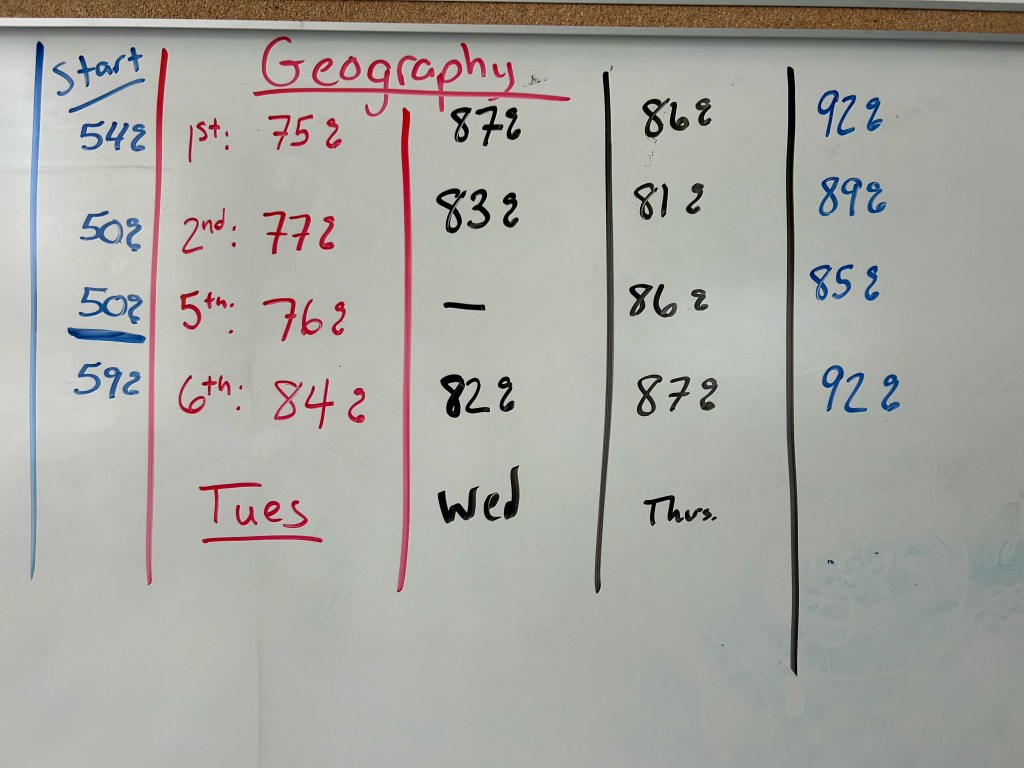

Next, I read the story The Town Dump and highlighted how objects in the dump tell the story of the town and its people, much like the artifacts from Dan Lewer’s primary source lesson tell a story about teenage life in 2024. I asked the students to think of an object or artifact they possess that tells a story about them, something they have held onto because it has meaning. After spending 15–20 minutes on this exercise, we finished the lesson on primary sources. I had the students use their descriptions, inferences, and questions to create two claims about teenage life in 2024. I included a 2xCER template on the paper I gave them because they were familiar with the format from the previous week. This was also an effort to incorporate general writing practice into my class. We concluded the class with a Gimkit about the states, where each question featured a picture of a state, and the students had to choose the correct answer. I noticed that our class average was stagnating at 65–70%, so I knew we needed to try something new.

Tuesday

On Tuesday, we started class with the same Gimkit from the previous day. This time, however, I gave the students a blank map of the United States. If they got a state wrong, I had them pause, locate the state on the map, and label it. I also mentioned that I expected a 90% class average by the end of the week, and I would be taking it for a score. Following the Gimkit, I introduced the concept of sourcing to the students. We began with a Frayer model for the word “sourcing.” I’ve been trying to incorporate the use of context clues to help create definitions for words, but the students are really struggling with this skill. I also included “two questions you would ask when sourcing” and examples of “good sources” and “bad sources.”

I took a screenshot of my Frayer, uploaded it to ChatGPT, and had it create a quick, one-paragraph reading to help the students fill in the Frayer boxes. I linked the reading to the Frayer. Afterward, I created an Annotate and Tell activity with some quick newspaper advertisement snippets and related questions. However, I soon realized that I was overwhelming the students with too much information. I wanted the focus to be on reading a secondary source newspaper article about the history of their community, Batavia, Ohio. So, during the second half of the day, I replaced the Annotate and Tell with an 8pArts sourcing template.

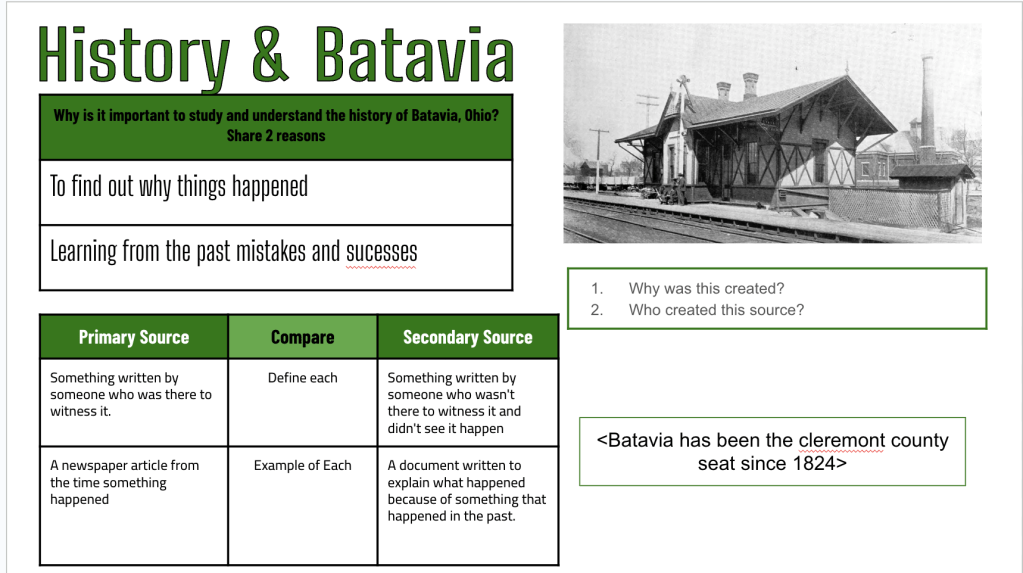

The main part of the lesson involved reading an article about the Batavia Bicentennial and creating a thick slide. I used the 8pArts template to guide students in practicing sourcing and breaking down a document. The template included a three-word title, content, contextualizing, sourcing, and communication (author’s purpose). I provided the Batavia Bicentennial article to the students and asked them to scan the article’s title and headings to predict its content by creating a three-word title. We then sourced the article, discussing who the author was and when it was written. We also contemplated why it was written—to celebrate the bicentennial of Batavia.

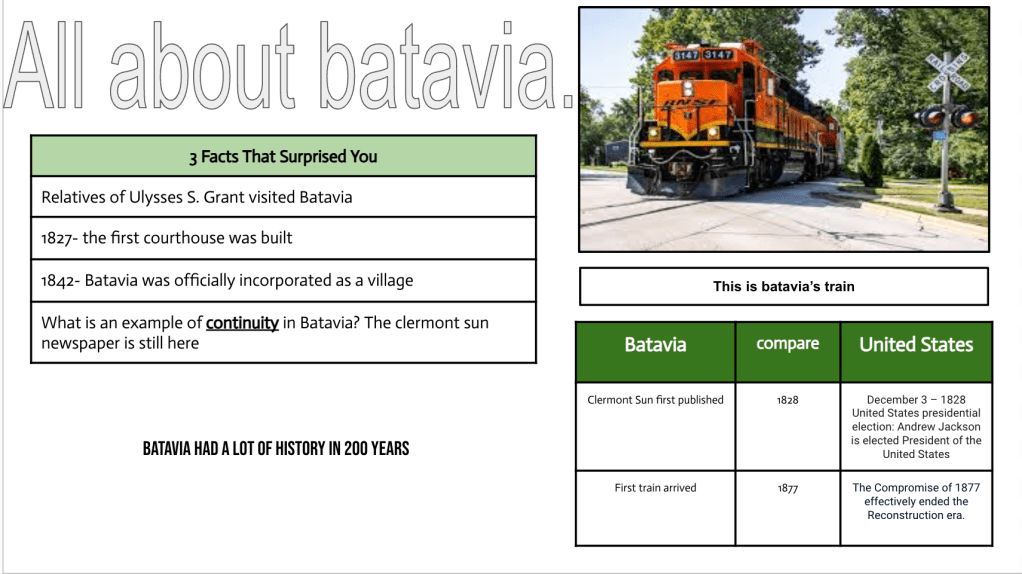

Once we completed these steps, it was time to read the article. I asked the students how long they thought it should take to read it. Answers varied from 10 minutes to as little as 2 to 3 minutes. I informed them that it should take about 3 minutes, which surprised some and relieved others. Many students tend to overestimate reading time and shut down before they even start. After reading, the students listed three interesting facts under the content/details section. Finally, we contextualized the information and determined it was about Batavia’s Bicentennial. I explained the term bicentennial, breaking down the word into “bi,” meaning two, and “centennial,” meaning 100, to help them understand.

In the middle of the 8Parts template was a space to summarize, but I instructed them to create a Thick Slide as their summary. On the Thick Slide, students included three interesting facts from the 8pArts template, a picture with a caption, and a title. We also reviewed the concept of continuity, a word we studied last week. I asked them to find and list an example of continuity from Batavia, and some identified that Batavia has been the county seat since 1824—great stuff! I also had them list two events that took place in Batavia in 1828 and 1877 and find two other events that occurred in the United States during the same years. Finally, they wrote a topic sentence that captured the main idea of their slide, reinforcing our focus on understanding the main idea.

Wednesday

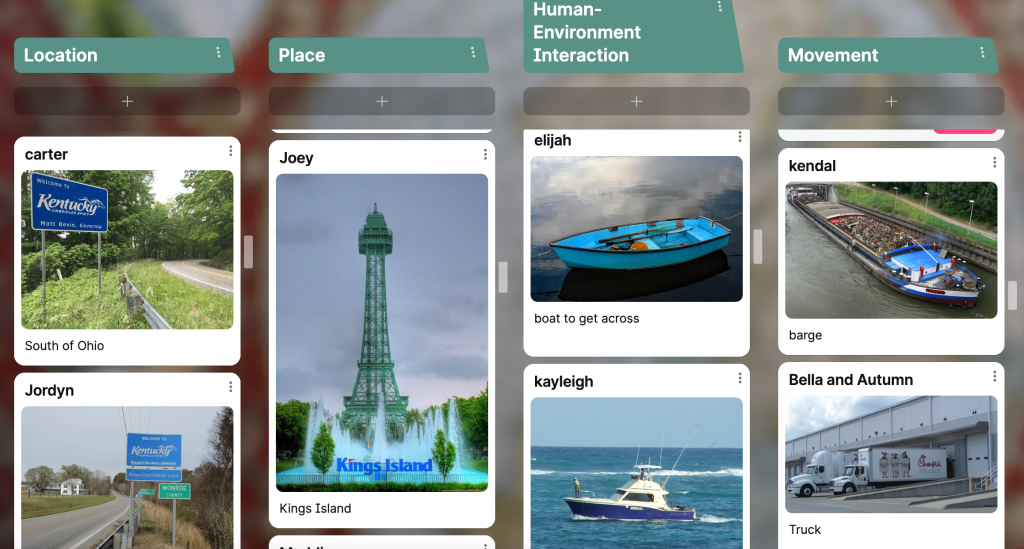

On Wednesday, we focused on the Five Themes of Geography using a Thin Slide activity. Instead of reading about the Five Themes, I decided to use a simple Thin Slide format. Initially, I attempted this on Google Slides, but halfway through the day, I switched to Padlet. I originally created a five-slide deck for each student, but I wanted to switch to Padlet so they could see each other’s ideas.

On Padlet, I set up five columns, one for each theme of geography: location, movement, place, region, and human interaction. I had the students relate these themes to Cincinnati. For example, they shared a city or state near Cincinnati and explained its relative location. Another example was how people in Cincinnati have interacted with and adapted to the Ohio River. Students shared one picture and one word or phrase for each theme, with a time limit of three minutes per theme. After completing the Thin Slides, the students created a personalized geography page where they added their favorite climate, a country they always wanted to visit, their favorite geographical feature, and more. We wrapped up the class with another round of Gimkit on the states, and this time, we achieved over 80% in each class, showing marked improvement.

Thursday

We began Thursday’s class with students finishing their personalized geography pages from the previous day, using the first 15 minutes of class to do so. Next, we did a Resource Rumble, where I asked questions related to historical thinking skills (primary and secondary sources, sourcing, continuity, and the Five Themes of Geography). Students went to the envelopes I had taped around the walls, answered the questions, and had me check their answers. After receiving feedback, they could roll dice and collect Jenga blocks. The team with the tallest tower won a prize from the unimpressive prize box. I had the students keep their answer sheets because they would need them for tomorrow’s assessment. This activity was part of my effort to show students that everything we do serves a purpose. I want them to take ownership of their learning and place importance on every activity. We ended the class with another round of Gimkit for practice before our final attempt on Friday.

Friday

On Friday, we started with a final round of the Gimkit about the states. I reviewed the class averages from the beginning of the week—54%, 50%, 50%, and 59%. I set the Gimkit timer for eight minutes and made a deal with them: if everyone answered 32 or more questions and the class average was 90% or higher, everyone would receive a score of 100%. The results were promising—first bell met the challenge with a 92% average, second bell achieved 89%, fifth bell reached 86%, and sixth bell finished strong with 92%. I’ve always struggled to get other classes above 80%, but looking back, giving the students a blank map to label when they missed a state question made a significant difference.

The next part of our assessment was using a Thick Slide to demonstrate their historical thinking skills. On the Thick Slide, students created a title that encapsulated the main idea of the topic, listed two reasons why it’s important to study the history of Batavia, OH, found a historical image of Batavia and used the caption to source it (by asking questions about it), compared primary and secondary sources, and listed an example of continuity. The students could use their Resource Rumble paper from Thursday’s lesson to help them complete the slide. I gave the students 25 minutes to complete this assessment.

During this assessment, I incorporated a new feature I learned from Jake Carr about using Claude to create artifacts, such as multiple-choice quizzes, short answers, or essays, and to provide feedback. Jake showed me how Claude could generate a code to create an artifact that could be shared with others. This led me to wonder, “Can I create an artifact where students can paste a link to their Thick Slide, and Claude analyzes it and gives instant feedback?” I worked on and reworked a prompt to set this up.

Here is the prompt I created:

“Create an artifact that provides consistent, quality feedback for 7th-grade students’ Thick Slide submissions on historical thinking skills. The feedback should focus on the following areas:

- Reasons for Studying History:

- Understanding the past to inform the future.

- Learning from past mistakes and successes.

- Building cultural awareness and empathy.

- Developing critical thinking and analytical skills.

- Preserving collective memory and identity.

- Sourcing Questions:

- Who created this source?

- When was it created?

- Why was it created?

- What is the creator’s perspective or bias?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Definitions of Primary and Secondary Sources:

- Analyze how accurately students define and differentiate between primary and secondary sources.

Rubric Development:

- Design a rubric that includes criteria for evaluating each of the three focus areas (reasons for studying history, sourcing questions, and definitions of primary/secondary sources).

- Ensure the rubric provides clear, 7th-grade-level descriptions for each criterion, allowing for objective and consistent grading.

Artifact Creation:

- Use the rubric to generate an artifact (such as a feedback template) where students can copy and paste their Google Slide link.

- The artifact should automatically provide quality, constructive feedback based on the rubric’s criteria.

- Feedback should be designed to guide students in improving their understanding of historical thinking skills while being accessible at a 7th-grade reading level.

Consistency and Quality Control:

- Implement measures within the artifact to ensure that feedback remains consistent across different student submissions.

- Ensure that the artifact is free from errors and provides accurate, relevant feedback tailored to the student’s work.”

After the artifact was created, I shared the link with the students. It was easy to access and use, and while some students found it helpful, others noted that it inaccurately told them they hadn’t completed certain tasks that they actually had. The feedback was varied, and the Claude feedback was inconsistent, but it’s still a work in progress. There’s a lot of potential here for some cool developments.