Monday – Mercantilism Rack and Stack

Tuesday and Wednesday – Stations, Questions

Friday – Colonial Government Vocab, Finish the Drawing

Monday

The Question That Drove the Lesson

This week’s focus was one word with a big question behind it: How did mercantilism shape opportunity and inequality in the 13 colonies?

Starting with Context

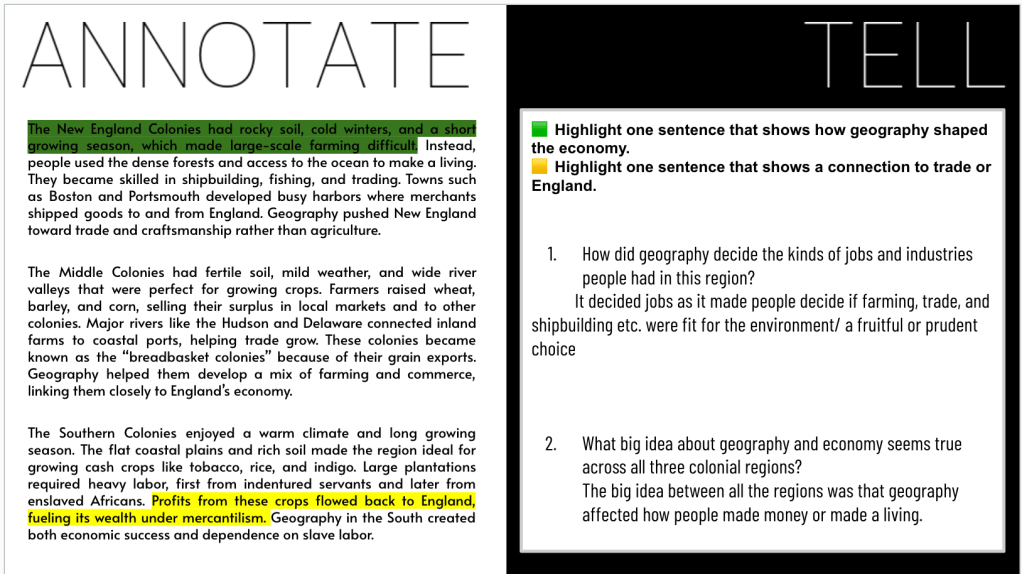

We began with an Annotate and Tell that served two purposes. It was both a review of the colonial regions from Friday and a bridge into mercantilism. Students highlighted how geography shaped each region’s economy and how trade connected everything back to England. It set the stage well. New England’s harbors, the Middle Colonies’ fertile valleys, and the South’s long growing seasons all played a part in fueling England’s wealth.

Building the Definition

Next came the Frayer. I wanted students to define mercantilism on their own terms. The first box asked for their current definition. Half wrote “I don’t know,” and that was fine. The other half offered short guesses that showed small pieces of understanding from previous Gimkits.

Then I showed a clip from Pocahontas called “Mine, Mine, Mine.” It is dramatic and exaggerated, but it captures greed and the idea of the mother country taking resources. After watching, students revisited their definitions and began to write with more confidence.

Seeing the System

After that, we moved into an Annotate and Tell Battleship using an image of a queen at a table labeled “Mother Country,” being served gold, foodstuffs, and raw materials by smaller colonies. Students selected coordinates, described what they saw, and discussed what it revealed about power, wealth, and control. That visual made the system of mercantilism visible and concrete.

Students returned to their Frayer once more, combining what they had seen, heard, and analyzed. Their final definitions showed clear growth.

Sharing and Reflection

To close, students shared their finished definitions on Padlet. No two were the same, which was exactly the point. I have decided that I will never have students copy definitions straight from a text. That is not learning. Real learning happens when students build meaning themselves.

Why It Mattered

This lesson was not about memorizing a vocabulary word. It was about constructing understanding through experience. Students moved from “I don’t know” to defining an economic system that shaped colonial life. They saw that mercantilism was not just about trade. It was a system that created opportunity for some and inequality for others.

By the end of class, one Padlet post summed it up perfectly:

“Mercantilism is when the colonies work so the mother country gets rich.”

Simple. Clear. And completely their own.

Tuesday and Wednesday

Because of another shortened schedule, this lesson stretched across Tuesday and Wednesday. What’s interesting this year is that my students can move through lessons faster than in the past, yet the constant interruptions and odd schedules keep everything slightly off balance. I’m about a week and a half behind where I was last year, but honestly, the depth of discussion this week made it worth it.

The goal was to uncover the inequality side of mercantilism, to show how England’s wealth depended on a system that included slavery. We started not with a video or text, but with a rectangle of painter’s tape on the floor, six feet long and sixteen inches wide. On the screen, a diagram of the slave ship Brookes. Students began asking questions right away: Why that size? Why that shape? Then I told them that this was the amount of space an enslaved man was confined to on the Middle Passage for two to three months. The room got quiet. That visual, standing over that space, did what no paragraph could.

From there, students rotated through five stations designed with intention. Station 1 was a TED-Ed video on the Middle Passage. Station 2 was a triangular trade map that connected back to the mercantilism we had studied earlier. Station 3 was an excerpt from Olaudah Equiano’s narrative that gave a human voice to the experience. Station 4 tied the Middle Passage directly to mercantilism, showing how enslaved labor kept the system running. Station 5 used the interactive Slave Voyages map, where dots appeared year by year, each dot a ship carrying people across the Atlantic. Watching the screen fill up was its own kind of silence.

At the end, students answered our supporting question again: How did mercantilism shape opportunity and inequality in the 13 colonies? Their responses showed real connection. Many wrote that England’s “opportunity” was built on the labor and suffering of others.

Thursday

Thursday was one of those days where I just did not have it. I overthink everything because I want every lesson to be intentional and meaningful. Ninety-five percent of the time I can deliver. This was my five percent.

I knew the next phase of the unit was government, but I could not land on the right way to start it. I kept thinking and planning, but nothing felt right. I gave a 13 Colonies map quiz to start class, and it took longer than I expected. I tried to begin my new lesson on colonial government but stopped midway through because I did not like how it felt.

So, I called an audible. We played Jeopardy Gimkit for retrieval practice and review instead. It was not my most polished day, but sometimes the most honest thing a teacher can do is pivot, regroup, and protect the energy of the room.

Why It Mattered

Not every day has to be perfect to matter. Thursday was a reminder that teaching is a rhythm, not a script. Some days are for deep reflection and connection. Others are for keeping things moving and letting students win a few rounds of Gimkit. Either way, the learning continues, even when the plan changes.

Friday

By Friday, I finally got my act together and realized I needed to introduce some vocabulary about colonial government. We began with a Gimkit that focused on words like limited government, Magna Carta, self-government, and representative democracy. We played for four minutes, then paused so I could give quick feedback.

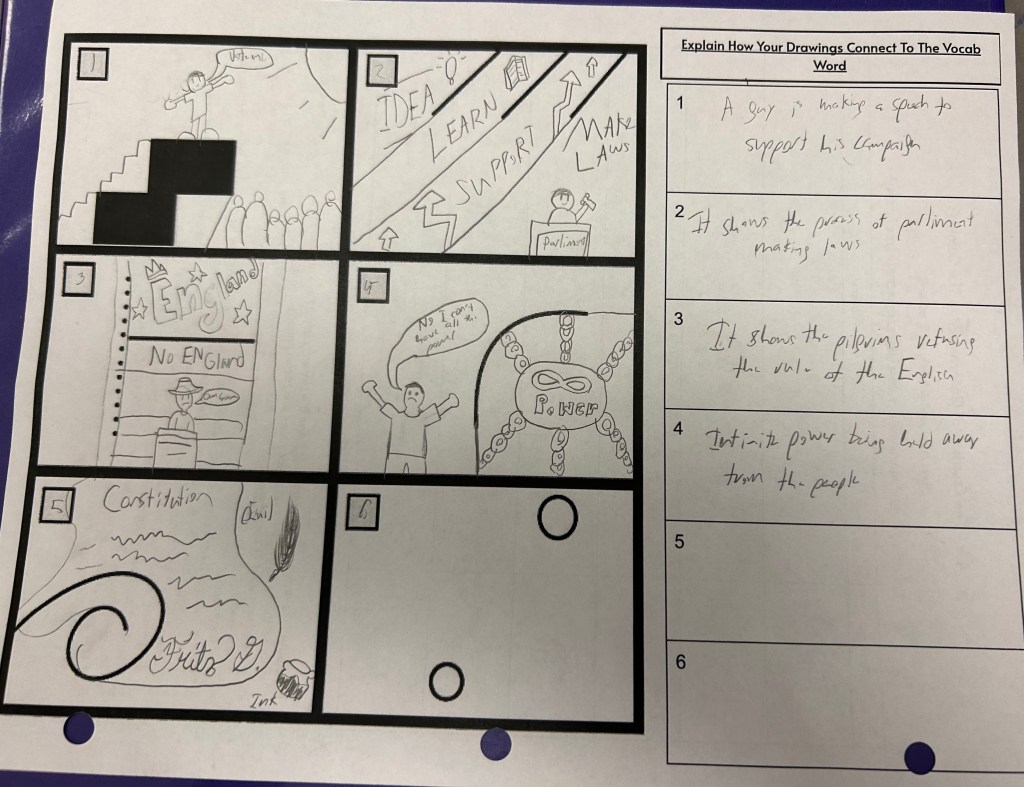

Next, I handed out a two-sided vocabulary page. On one side, students wrote down six vocabulary words in the first column. Then we brought out the triangular dice. Each side of the die has three numbers, and the number that landed face down decided how many words their definition could include. The rule was simple: no copying straight from the book. The dice forced them to paraphrase and negotiate meaning. I heard great partner discussions about which words to keep, which ones to cut, and how to reword definitions using synonyms. It was twelve minutes of authentic thinking.

After that, I wanted them to process the vocabulary in a creative way. We used a Howson History lesson called Finish the Drawing. Students randomly numbered their unfinished sketches one through six. Then I gave prompts: “Show a characteristic of a representative democracy” for box one, and “What is the job of Parliament?” for box two. Each prompt pushed them to visualize meaning, not just recite it. I love this activity because it lets students demonstrate understanding in ways words alone cannot capture.

Why It Mattered

This was the first day all week that felt balanced again. Students were learning, talking, and creating. They were not memorizing terms; they were making sense of them. The combination of movement, creativity, and conversation made abstract government ideas more concrete.