This unit started with a question that actually mattered:

If you lived in England in the 1600s, would you have left and risked it all?

That single question framed the entire unit. Every activity, reading, and discussion tied back to it. When students know the “why,” it changes how they engage, instead of memorizing colony facts, they were weighing survival, opportunity, and risk.

Staging the Question: Setting the Hook

We started with Number Mania, a tip chart, and a Fast and Curious Gimkit — three low-barrier, high-engagement routines that get every student involved right away.

- The Gimkit Fast and Curious built repetition and retrieval practice. Students could fail safely, learn quickly, and get competitive energy going. After a three-minute round, we wrote the most-missed words on a tip chart.

- I rolled dice to determine how long their definitions should be, which gamified paraphrasing and reduced the “copy the glossary” habit.

- They added quick sketches for dual coding (pairing visuals with words), which built stronger recall.

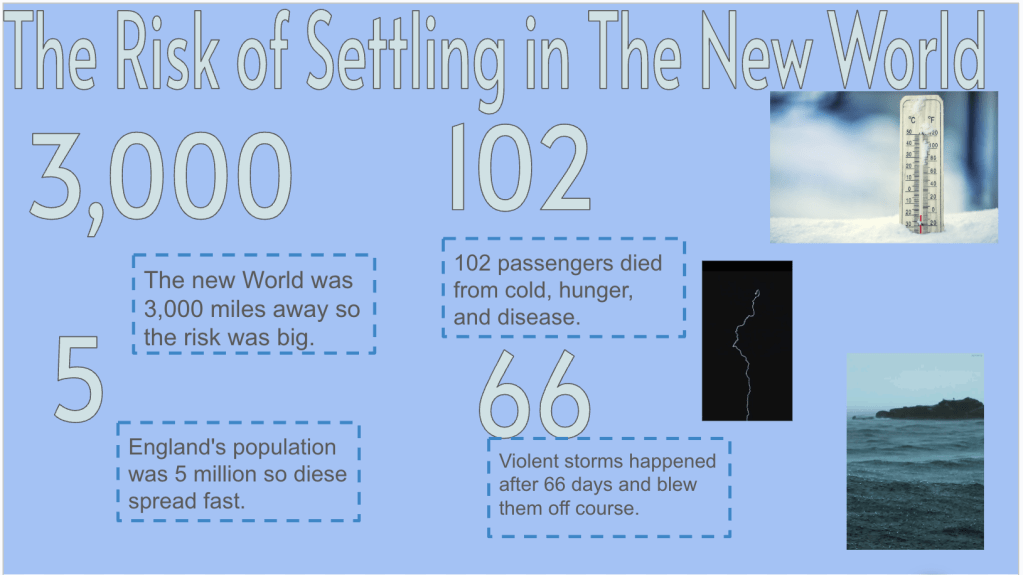

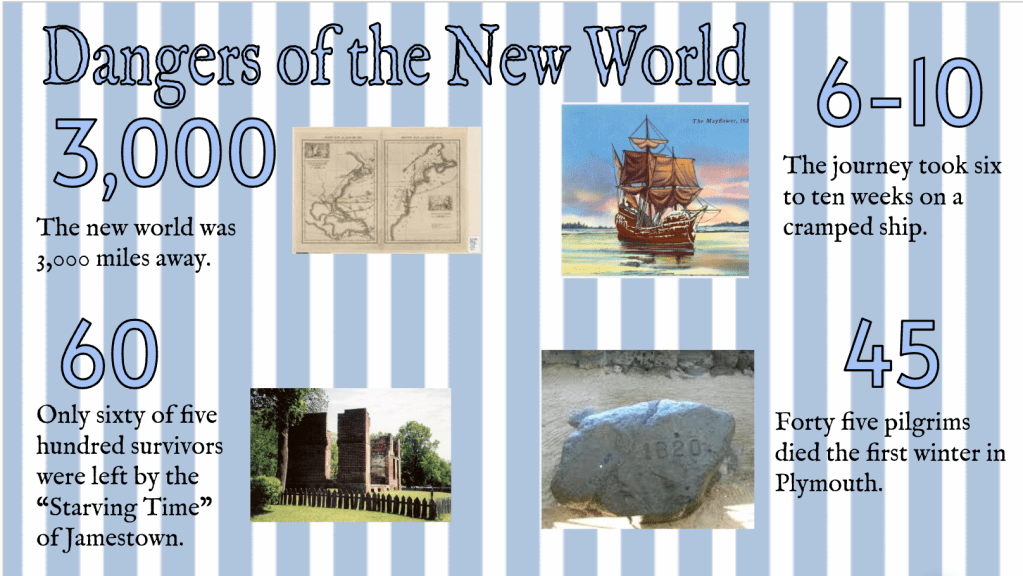

The Number Mania gave the unit real world context. The reading included key facts and data, how long the trip took, how many died, what they brought, etc. Students created visuals using four numbers that proved leaving England was a dangerous gamble.

This sequence made sense because it layered curiosity and background knowledge without bogging students down in heavy reading yet. Everyone started with success, visuals, and movement, not lectures.

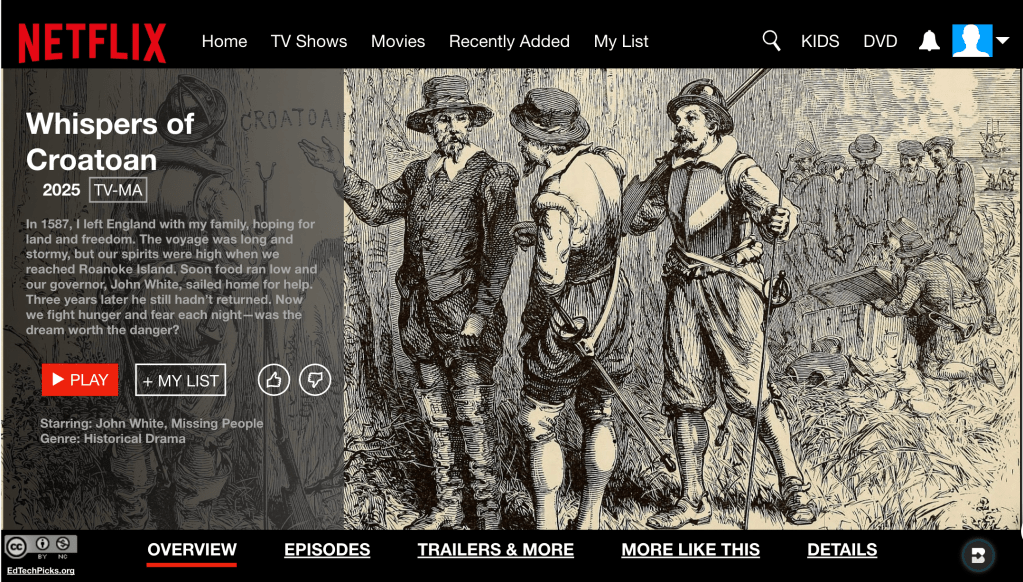

Roanoke: Launching the Inquiry

Our first supporting question:

What do you believe happened to Roanoke?

Students explored five theories and worked in teams to weigh evidence for each. It was a perfect launch because Roanoke’s mystery has built-in curiosity — students naturally argue about which theory makes sense.

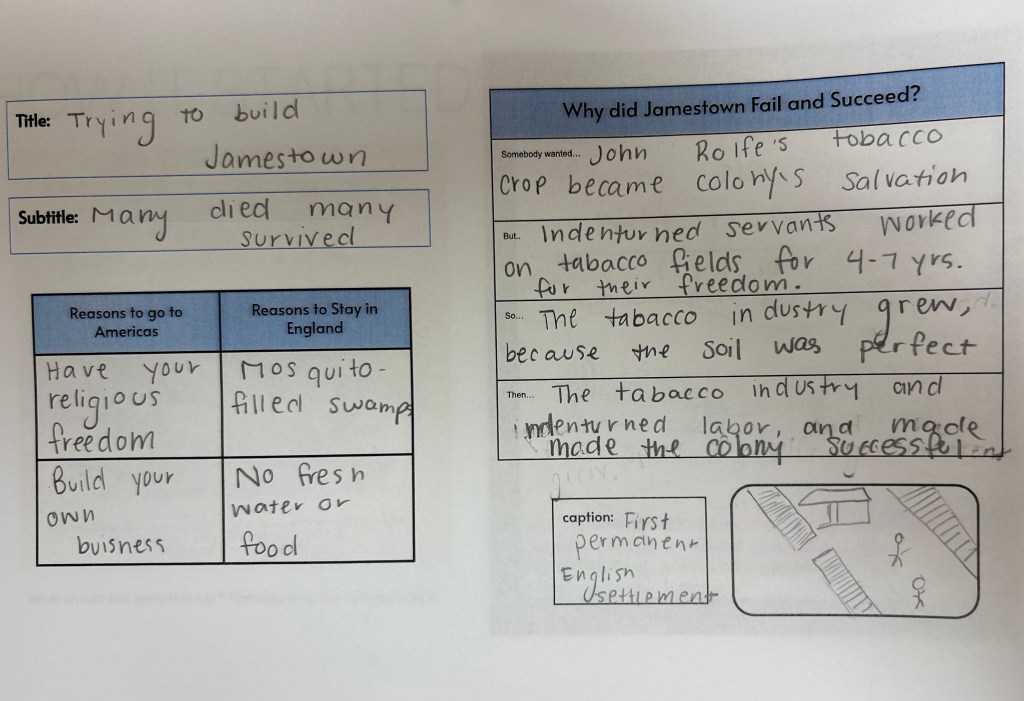

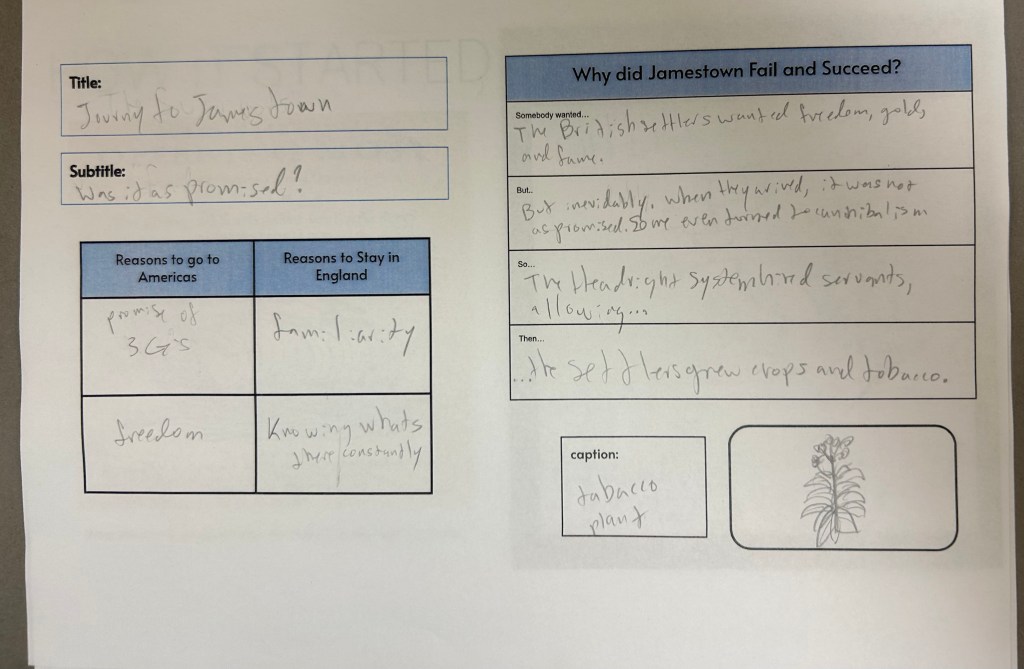

They wrapped up by creating a Thick Slide summarizing their claim with a title, subtitle, image, and short reasoning. I also had them list “reasons to go vs. stay in England.” It wasn’t essential in hindsight, but it kept the throughline alive: every lesson connected back to that main question about risk.

The design choice here was intentional — open-ended inquiry first, clear structure second. The mystery of Roanoke pulled them in emotionally; the Thick Slide gave structure for reflection and writing.

The Side Quest: Passenger Lists

Before jumping to Jamestown, we used the DIG (Digital Inquiry Group) passenger list lesson. The questions:

- What can passenger lists tell us about who immigrated?

- What can that tell us about life in the colonies?

At first, I wasn’t sure if this fit, but it turned out to be the perfect bridge. Students analyzed real names, occupations, and destinations, seeing patterns between who left and where they went. It subtly prepared them for the summative project, where they’d create fictional lives set in this same context.

The side quest worked because it slowed the pacing just enough — students practiced evidence-based reasoning without jumping straight to another big event.

Jamestown: When the Dream Meets Reality

Supporting Question #2:

Was Jamestown really the “opportunity” the Virginia Company advertised?

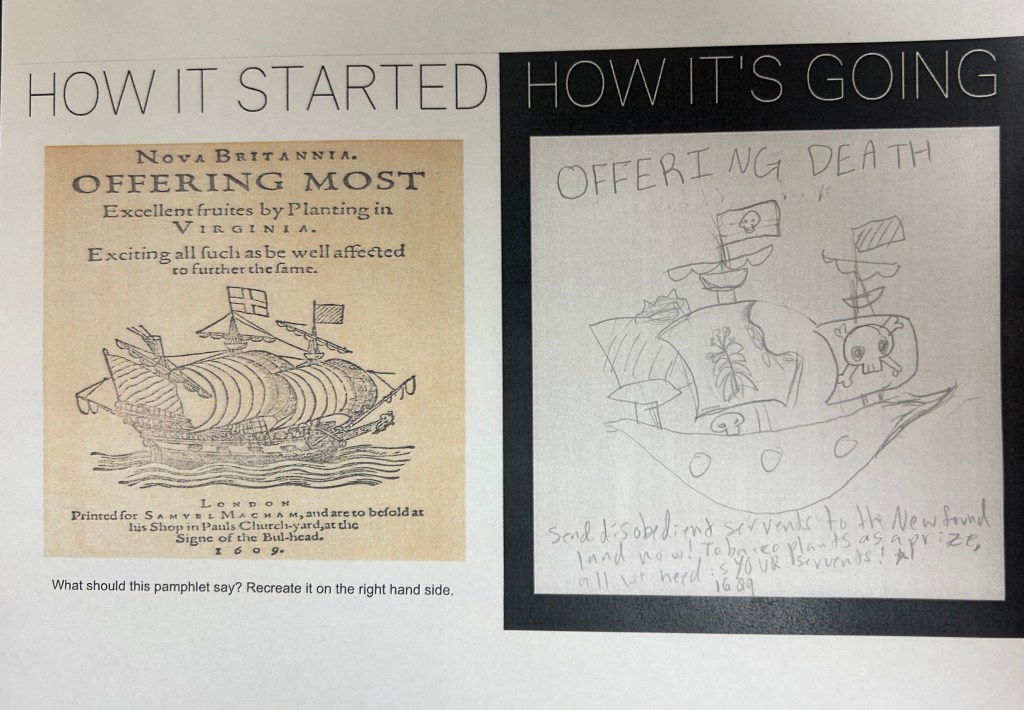

We began with Justin Unruh’s Annotate and Tell Battleship using a real Jamestown advertisement. Students analyzed coordinates on the ad to find small details: promises of gold, comfort, and easy living — and shared their discoveries. The format made close reading competitive and concrete.

Then I asked, “Imagine that ad convinced you to go. You survive the voyage and land in swampy, mosquito-filled Jamestown. What’s your first move?”

Around the room were four choices: “Find Gold,” “Find Food,” “Build Shelter,” “Trade with Natives.” Each station had short readings labeled with emojis…skull (you died) or gold star (you survived).

It took about 10 minutes for students to realize that almost everyone “died.” That visual punch, seeing classmates hold up skull papers, made the hardships real. It’s an experience they’ll remember far longer than a paragraph in a textbook.

Students then made another Thick Slide using the “Somebody, Wanted, But, So, Then” structure. We closed the loop with How It Started vs. How It’s Going, having students rewrite the Jamestown ad truthfully…no more propaganda.

The reason this sequence worked: it moved from persuasion…reality…reflection. Students analyzed sources, made a personal decision, saw the consequences, and reevaluated the message.

Plymouth: Community and Cooperation

Supporting Question #3:

How did the Pilgrims build community and succeed in Plymouth?

We used Deja Voodoo from EMC2Learning, a structured rereading strategy that forces multiple passes through the text. Each round had a clear purpose:

- Identify every hardship the Pilgrims faced.

- Write a claim about their greatest hardship using evidence.

- List ways religion influenced their choices.

- Explain how they worked together to survive.

Each round shortened, increasing urgency and focus. Groups discussed between rounds and shared key takeaways. The setup pushed them to reread for different purposes. It’s great for students who struggle with comprehension.

We closed with a final Thick Slide that summarized their findings visually and verbally. These became anchor slides for the summative assessment.

The sequence worked because students were constantly doing something: reading, writing, talking, deciding. Engagement stayed high because each round built momentum and required evidence based thinking, not passive recall.

The Summative: The Netflix Series

Finally, we circled back to the main question:

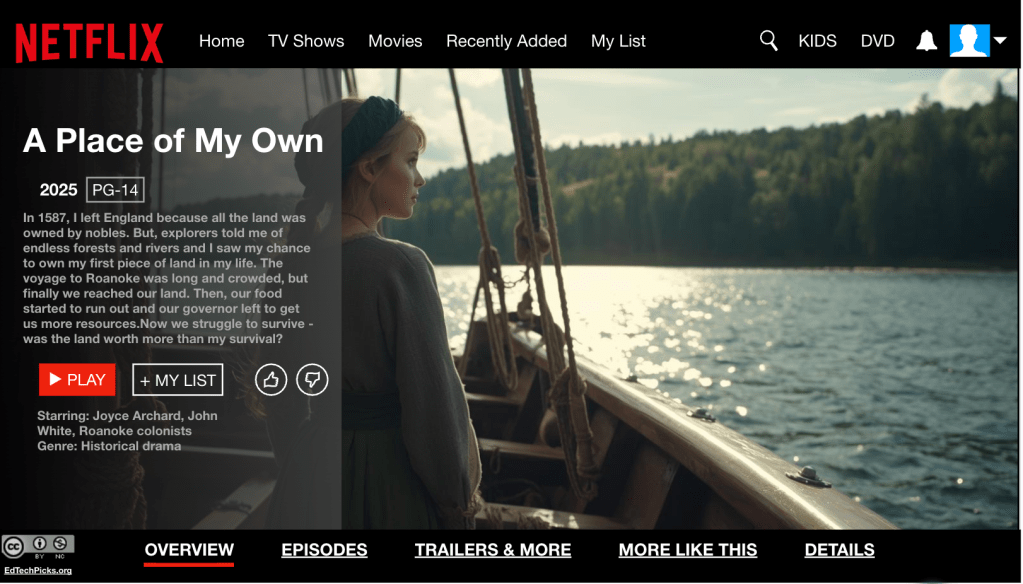

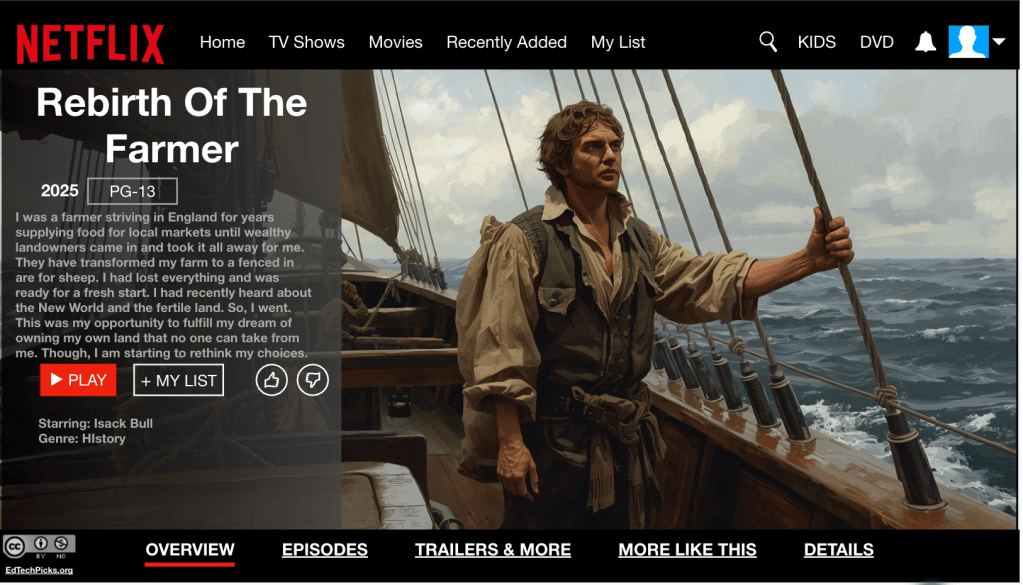

If you lived in England in the 1600s, would you have left and risked it all?

To avoid everyone saying “no,” I added a twist…I asked ChatGPT to create 13 realistic life scenarios. Students randomly drew cards: an indentured servant, an apprentice, a religious dissenter, a missionary, and so on. Each card forced them into the mindset of someone who had to leave and choose between Roanoke, Jamestown, or Plymouth. Some of the cards made it obvious which colony they were going to, and some left it open ended to they could pick any colony they wanted.

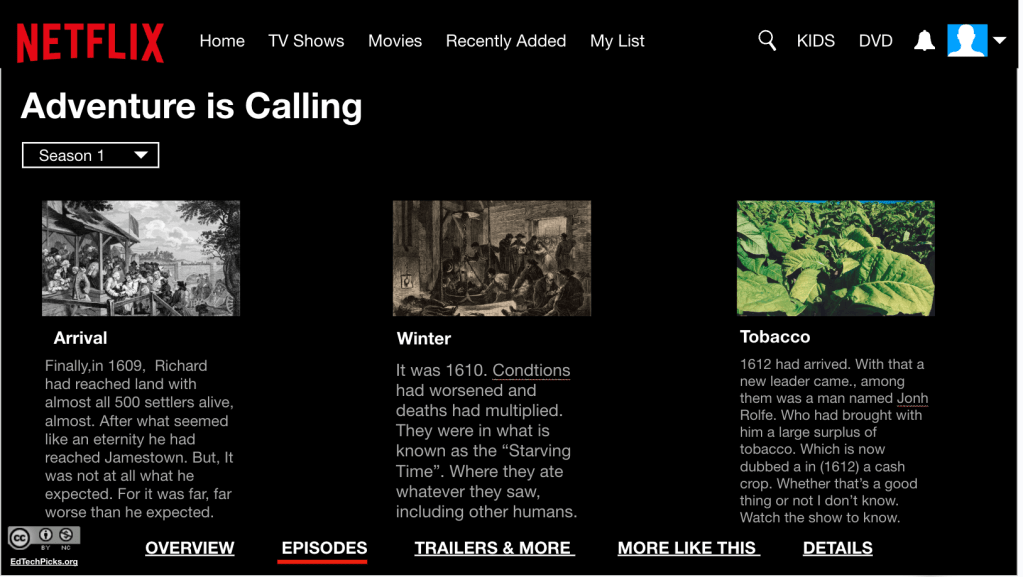

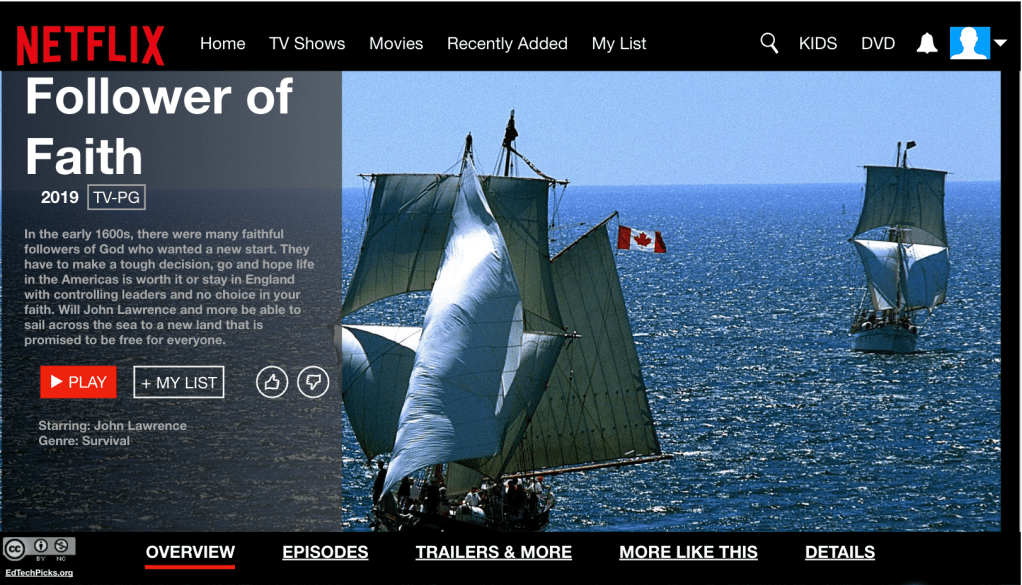

Their final task was to turn that journey into a Netflix style show:

- Episode 1: The voyage (connected to Number Mania).

- Episode 2: The struggles and survival (connected to Jamestown/Plymouth).

- Episode 3: Success or failure (connected to community and adaptation).

Some students even used real names from the passenger lists. That unplanned crossover was proof that the structure worked — students saw the throughline from start to finish.

Why This Sequence Works

This wasn’t three disconnected colony lessons…it was a layered experience that kept looping back to one big idea: Was it worth the risk?

Here’s the logic behind the sequence:

- Staging the question gave students curiosity and vocabulary.

- Roanoke hooked them with mystery and decision-making.

- Passenger Lists built background on who came and why.

- Jamestown showed the harsh reality behind the “opportunity.”

- Plymouth offered a counterexample — a colony that learned cooperation.

- Summative Netflix project tied all those threads together with creativity and choice.

Every step required students to think, not just recall. They compared, analyzed, visualized, and argued. Engagement stayed high because the protocols rotated, Gimkit, Number Mania, Annotate and Tell, Deja Voodoo, Thick Slides; all with short bursts of energy and clear outcomes.

Links for the Unit

Staging the Question – Number Mania, TIP Chart for Vocab

Roanoke – Roanoke Lesson (reformat yourself if needed), Thick Slide

Jamestown – Annotate and Tell, Thick Slide, How It Started

Plymouth – Thick Slide and Reading

Summative – Netflix, Directions