I’m going to frame this week’s post around the beginning, middle, and end of the week. Once again, our rhythm was shaped by shortened schedules and shadow days, which meant adjusting plans and finding ways to keep learning moving forward. To work around the interruptions, I started the week with a take-home test, then rolled out a new unit built around a compelling question: “Would you have risked everything and left England during the 1600s for a chance at a better life?” We staged the question with a round of Number Mania and some key vocabulary, giving students both the facts and the language to start thinking about the risks and rewards of leaving home. By the end of the week, we shifted gears into the mystery of Roanoke, weighing different theories and examining evidence to see how stories about the past are pieced together.

Early in the Week

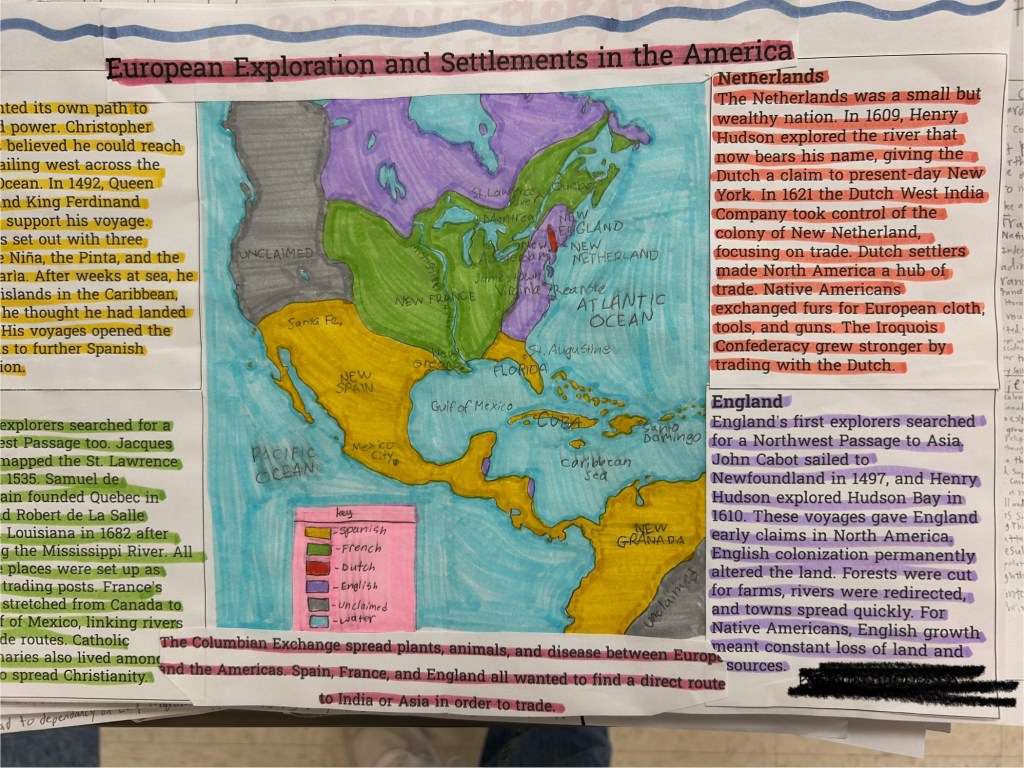

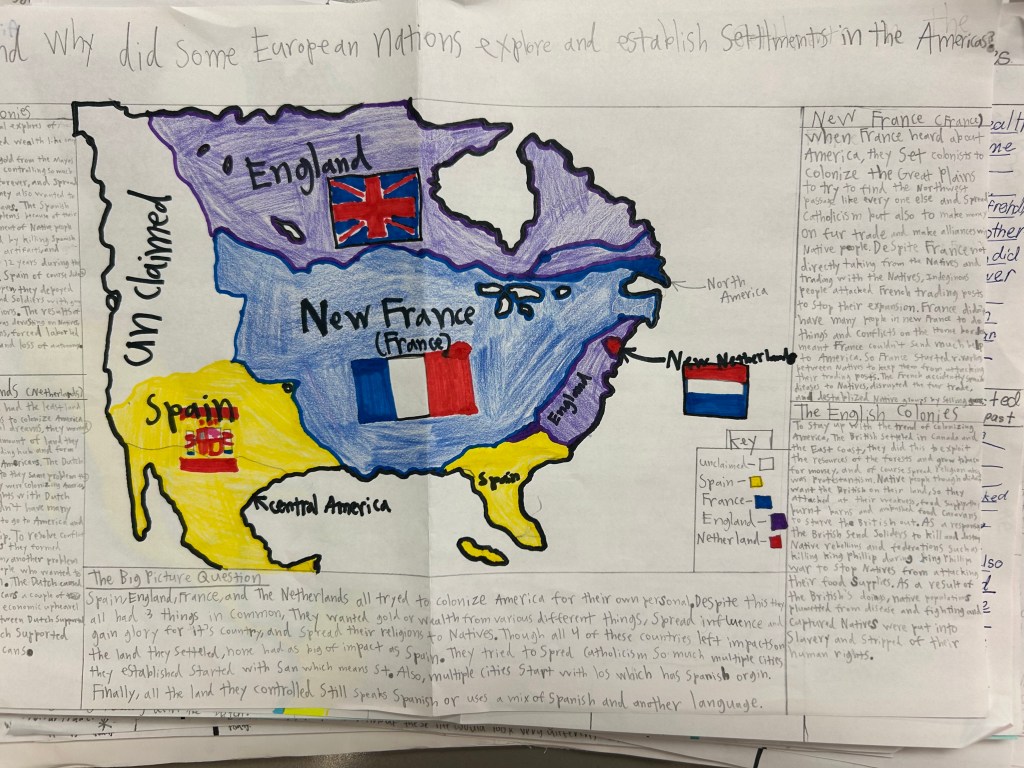

Early in the week, I gave students a take-home test and let them use the entire class period to work on it. When I first mentioned “take-home test,” they got excited and thought it would be an easy multiple-choice packet. I laughed and told them, “Do you really think I’m going to give you a multiple-choice test to take home? No way.” Instead, the assignment was an annotated map. Students outlined North and Central America, colored and labeled the territories of Spain, France, England, and the Netherlands, and created a title and key. Around the map, they wrote Somebody–Wanted–But–So–Then stories for each country, explaining motives, challenges, actions, and effects. Finally, they answered a big-picture question about which country left the biggest long-term impact on North America and why.

Working Through the Assignment

I set it up this way because our schedule has been unpredictable. Some days we have 40–45 minutes, others just 30, and sometimes classes disappear altogether because of shadow days or shortened schedules. The constant stopping and starting makes it hard to keep a steady flow. This format let me keep the class moving forward while also giving students a creative way to show what they had learned.

Why It Mattered

The take-home test worked because it balanced structure with freedom. Students weren’t just filling in blanks or circling answers. They had to demonstrate knowledge by connecting maps, stories, and big-picture ideas. For me, the best part was seeing how they tied geography and narrative together to make sense of the bigger patterns of exploration.

Midweek

By Tuesday and Wednesday, we shifted into a new unit framed around the compelling question: “Would you have risked everything and left England during the 1600s for a chance at a better life?” So far, the overwhelming answer from students has been “no,” and not just in one class—it was a pretty consistent “no” across the board. I am already thinking ahead to the summative assessment and considering a twist. Students might roll dice to generate a scenario for their “made-up life” in England, which could force them to think differently about the risks and rewards of leaving.

Staging the Question

To stage the question, we started with vocabulary through Gimkit and a TIP chart. TIP stands for term, information, and picture. We opened with a Fast and Curious Gimkit round that ran for three minutes. Class averages fell between 60 and 75 percent. After reviewing results, any word where the class scored below 90 percent had to be added to their TIP chart. To make sure students were not just copying definitions, I added another layer. I pulled out a triangular dice, and the number rolled determined how many words their definition could be. This forced students to underline and extract the most important words, then rewrite the definition in their own terms. After filling in their TIP charts, we played another round of Gimkit. This time, class averages jumped to 85 to 91 percent.

Building Context

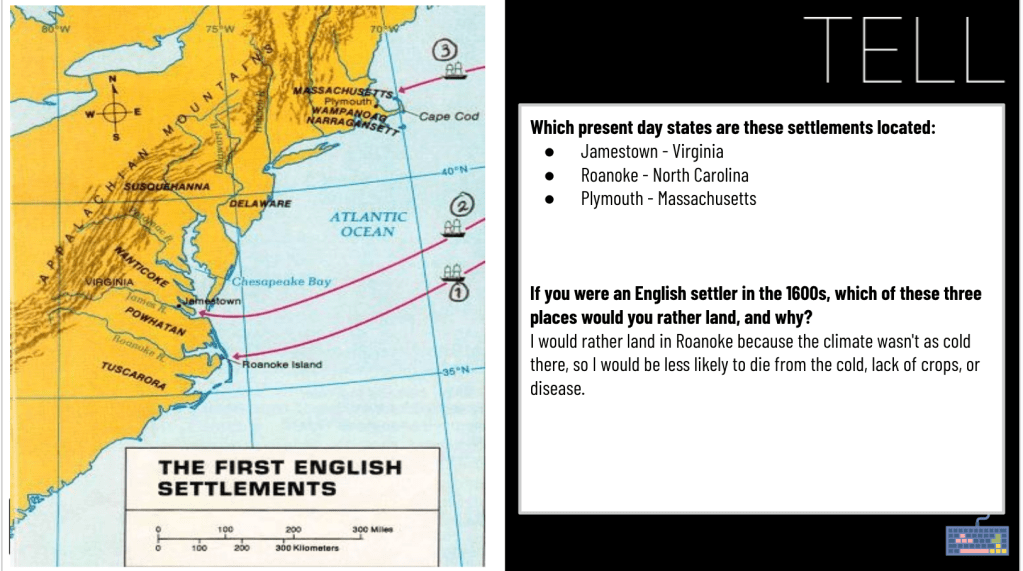

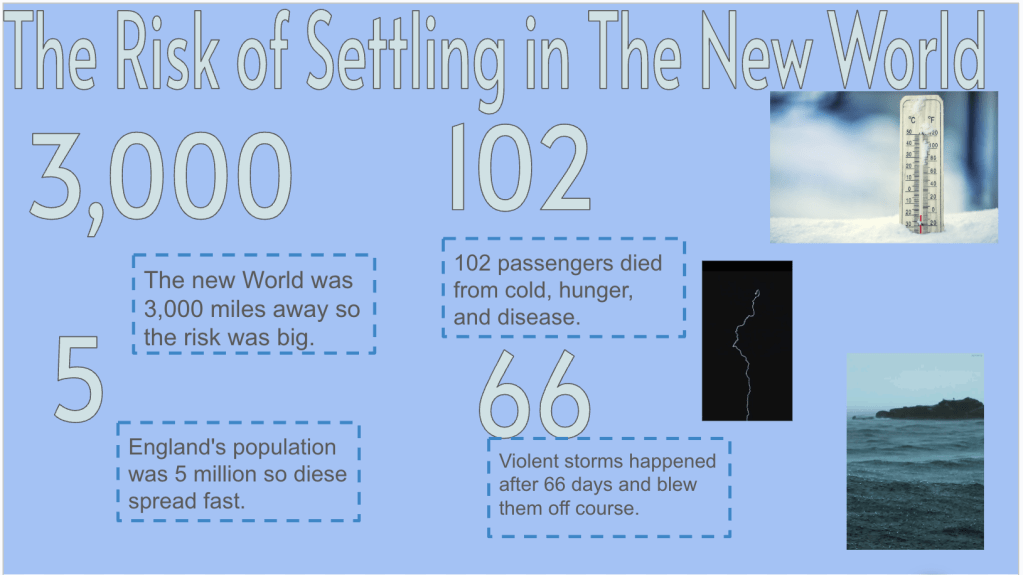

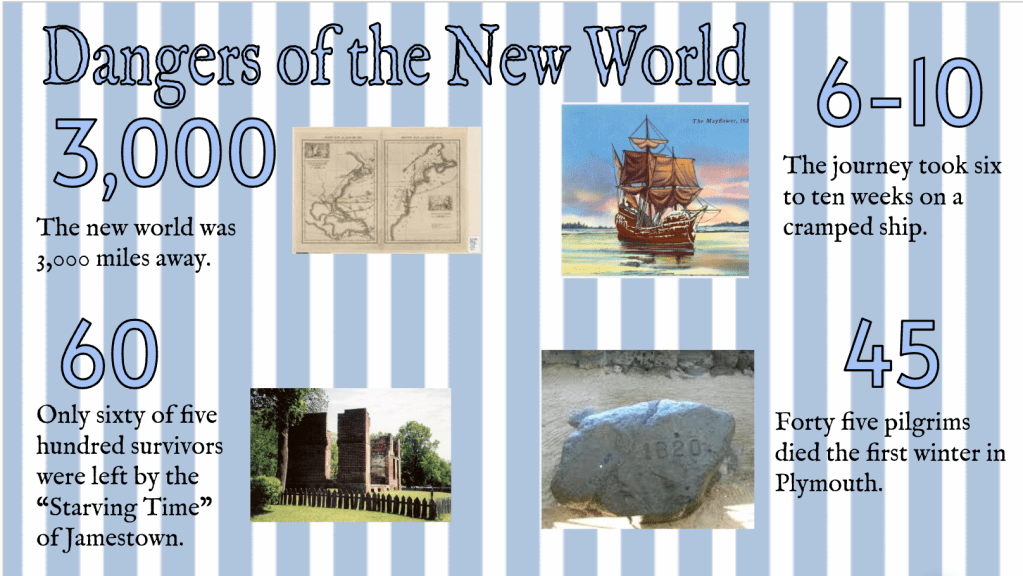

Once students had the language down, we moved into activities that helped them ground the question in time and place. With the Map and Tell, students had to figure out which modern-day states Jamestown, Roanoke, and Plymouth are located in. Then they discussed with a partner which settlement they would rather land at if they were an English settler in the 1600s, and why. For Number Mania, the goal was to prove the statement that leaving England and settling in the New World was risky and dangerous. Students picked four numbers from the reading, connected each to a fact, and organized their findings with a title and at least three pictures.

Why It Mattered

This sequence staged the big question with layers of vocabulary, geography, and data. Instead of simply asking students for an opinion, it gave them tools and context to support their reasoning. The dice added just enough unpredictability to make definitions more thoughtful, while the Gimkit runs gave immediate feedback on progress. By the time we finished, students had already begun to weigh whether leaving England in the 1600s was worth the risk, and most were firmly convinced it was not.

End of the Week

On Thursday, the 8th graders were out of the building visiting high schools for shadow days, so I gave the 7th graders time to continue working on their annotated maps. We also ran one more round of Gimkit with our vocabulary words, and this time the class averages all climbed above 90 percent. It was a good sign that the combination of TIP charts and repeated Gimkit play was paying off.

Roanoke Theories

On Friday, we dove into one of history’s mysteries with the supporting question: “What happened to the settlers at Roanoke?” I used a premade history lesson on Roanoke theories but trimmed it down to four main possibilities: the settlers went to Croatoan Island, they were killed, the Spanish attacked them, or they starved to death and were lost at sea. Then I added one more theory of my own—that John White knew the colonists were dead, discovered skeletal remains, but returned to England and lied about it to avoid scaring people away from the New World. Since these colonies were money-making ventures, it made sense that leaders would want to cover up failure and keep the dream alive.

Working Through the Evidence

I created a set of guiding questions for each theory to push students to consider evidence, reliability, and plausibility. After working through the theories, students summed it all up with a Thick Slide. They had to choose which theory they believed was true, explain their reasoning with evidence, compare reasons to go to the New World versus reasons to stay in England, draw a picture with a caption, and give their slide a title and subtitle

Why It Mattered

Friday was also the due date for their annotated maps, and 95 percent of students turned them in. What struck me most was the quality. These weren’t quick, surface-level assignments. Students had put care and detail into their work, showing that even in a week full of interruptions, they take the learning seriously and rise to the challenge.

Lessons Links For The Week

Beginning of the Week – Annotated Maps

Mid Week – Number Mania, TIP Chart for Vocab

End Week – Roanoke Lesson (reformat yourself if needed), Thick Slide