This week wasn’t about cramming in new content or racing toward a test—it was about building something that lasted. We used a layered mix of retrieval, reading, analysis, structured writing, and reflection, and each protocol helped us answer a bigger question. Coming off spring break, I knew students would need structure but also some momentum. So I stacked the lessons with intention.

We used Fast & Curious with Quizizz every day, not just to review terms, but to show how retrieval works when it’s spaced out and tied to deeper learning. We layered in Annotate & Tell for close reading and sourcing, and we used Graph & Tell to compare data with perspective. Students analyzed primary sources, revised flawed writing, and built arguments from multiple viewpoints.

We pulled in Archetype Four Square to reframe historical figures like Eli Whitney, then brought it full circle with Class Companion, Thick Slides, and a hands-on word wall review to tie everything together.

It wasn’t flashy, but it was meaningful.

Monday – Primary Sources, Questions

Tuesday – Cotton Gin Rack and Stack

Wednesday – Friday – Life of the Enslaved Rack and Stack

Truth with Sprinkles – Class Companion Link

Monday

We came back from spring break, and I knew better than to pretend everything would pick up right where we left off. After 10 days off, kids needed a ramp—but that didn’t mean the day had to be a throwaway. I wanted to build back some content momentum while still reinforcing writing skills. So I stacked the lesson around a clear essential question and layered the tasks with a mix of retrieval, source analysis, and structured writing.

Quizizz:

We kicked things off with a Quizizz that blended review and preview questions from our industrialization unit. The idea was to warm up their brains without pressure. It gave me a quick read on what stuck over break, what needed refreshing, and where we could push forward.

Primary Source Pack: Framed by a Big Question

The textbook has a set of primary source lessons—usually I tweak or skip them, but this one had potential. The essential question was:

How can changes in work and social life affect a society?

I ran all six sources through AI and had it reword them to be more accessible without losing meaning. I also had AI generate two basic questions per source to give kids a little guidance. After each source, students wrote a 6-word summary that directly tied back to the essential question. That’s what kept the focus. No wandering. Every source came back to that one big idea.

The sources included:

- A Lowell Mill girl’s journal

- An immigrant’s first letter home

- A factory owner’s defense of conditions

- A political cartoon from the time

- A protest flyer

- An anti-immigrant speech

Each gave students a different perspective, and the layering really helped them start to think critically about the intersection of work, immigration, and social change in the 1800s.

Short Answer: Revising a Bad Paragraph

Once we had enough content, I dropped them into a Short Answer task. I gave them a clearly incorrect paragraph that oversimplified everything. Their job was to revise it using evidence from the sources.

Here’s what they had to fix:

Changes in work and population didn’t really affect anything. Most people stayed on farms and worked outside. Immigrants had an easy time finding jobs and were treated fairly. Factory workers only worked a few hours a day, and their jobs were fun and safe. No one complained, and the government made sure everything was perfect.

The responses were solid. Short Answer let them see peer examples and compare their thinking, which always boosts engagement. We weren’t writing full-blown essays—just clean, focused revisions with evidence and reasoning. That’s the kind of writing practice that sticks.

Fast and Curious Again:

To finish class, we went back to Quizizz with a Fast and Curious round. It was the same set as earlier, but now students had background knowledge from the readings and writing. I wanted to see if the scores improved, and they did. Retrieval practice works—especially when the content is layered.

Tuesday

This lesson was all about getting students to see the layers of impact behind Eli Whitney’s invention—not just the praise in textbooks, but the real, complicated ripple effects. We used a mix of protocols to help students analyze, compare, and respond to those consequences.

Quizizz Check – Fast and Curious

We started with a Fast & Curious Quizizz round. The goal was to preview key terms tied to the cotton gin: invention, economy, agriculture, slavery, unintended consequences. I saw right away where the gaps were. Some students had never really connected the cotton gin to slavery. That told me the rest of the lesson needed to go beyond “Eli Whitney invented something helpful.”

Archetype Four Square: Who Was Eli Whitney?

Next, we moved into an Archetype Four Square. After reading a short bio of Eli Whitney, students picked an archetype they felt best represented him. Then we had them support it with evidence from the reading and make a historical or pop culture comparison. It sparked some great thinking. Was he a hero? A sage? A magician?

Annotate & Tell

From there, we jumped into an Annotate & Tell using two primary sources—newspaper articles from 1818 and 1825 celebrating the cotton gin. Students highlighted quotes that showed the invention’s impact: increased cotton production, land value, and Southern prosperity. Then we paused and asked the real question: What’s missing from this praise?

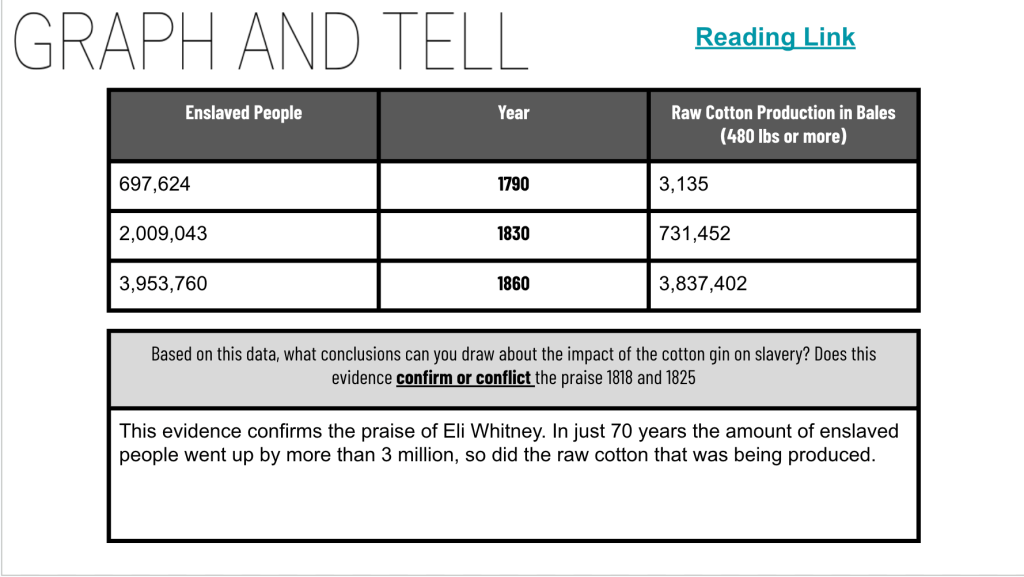

Graph & Tell

To bring in the other side, students examined a chart showing the rise of enslaved persons alongside the rise of cotton production. This was our Graph & Tell moment. They filled in a chart and wrote a short summary of what they noticed: a clear correlation between more cotton and more slavery. Then we pushed further—Does this data support or challenge what the primary sources said? That question changed everything.

Class Companion

To wrap things up, students went to Class Companion and wrote from a chosen point of view: Eli Whitney, a plantation owner, an enslaved person, or a Northern factory worker. Their task was to explain the consequences of the cotton gin from that lens, including both short- and long-term effects.

The AI feedback blew me away. It didn’t just give grammar tips—it recognized their POV and gave specific feedback tied to it. For example, students writing as enslaved people got suggestions on expressing emotion or explaining hardship more clearly. It was targeted, authentic, and helped them revise in real time.

Wednesday – Friday

Wednesday through Friday were choppy. State testing threw off our schedule, kids were in and out, and nothing was consistent. But in some ways, that made the lesson better. We had space to slow down and focus on the people most impacted by what we’d learned earlier in the week—enslaved individuals.

After exploring the unintended consequences of the cotton gin, we shifted into the question: What was life like for the people whose lives were changed by it? It wasn’t about moving on—it was about going deeper.

Starting with Language

We began with a short but important conversation about how we talk about people in history. I introduced person-first language:

- “enslaved person” instead of “slave”

- “enslaver” instead of “master”

- “freedom seeker” instead of “runaway”

I told students these words don’t just sound better—they shift how we see people. They’re human first. Not property, not background characters in someone else’s story. The kids caught on quickly and started using the new terms without being reminded. That one shift helped everything else land better.

Quizizz

Next, we ran a Quizizz. I built it around key vocabulary like abolitionist, resistance, enslaver, overseer, and oppression. I also kept a few questions from earlier in the week to bring back some of the Eli Whitney and cotton gin context. The goal wasn’t a grade—it was to activate thinking, catch misconceptions, and see what needed clearing up before we hit the heavier stuff.

A lot of kids didn’t fully understand “resistance,” so that told me where to lean in next.

EdPuzzle

We watched a high school-level EdPuzzle on slavery and resistance. I picked the 9–12 version on purpose—it talked about the Underground Railroad as a metaphor instead of a literal train line. That helped break a common misconception right away.

More importantly, the video gave a broader definition of resistance. It wasn’t just running away—it was breaking tools, learning to read, preserving family bonds, working slowly on purpose, singing coded messages in songs. It gave them a new way to understand how enslaved people fought back.

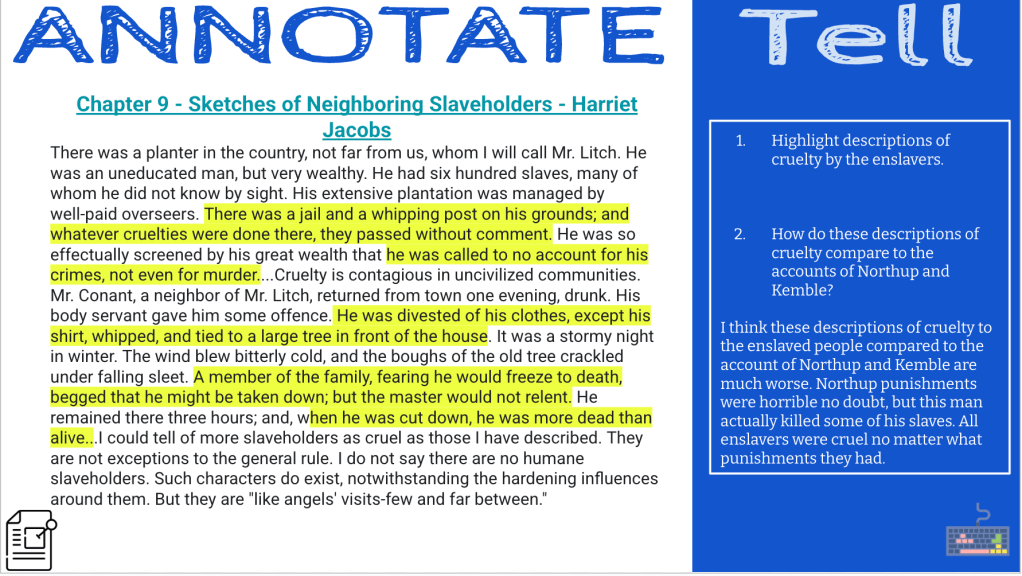

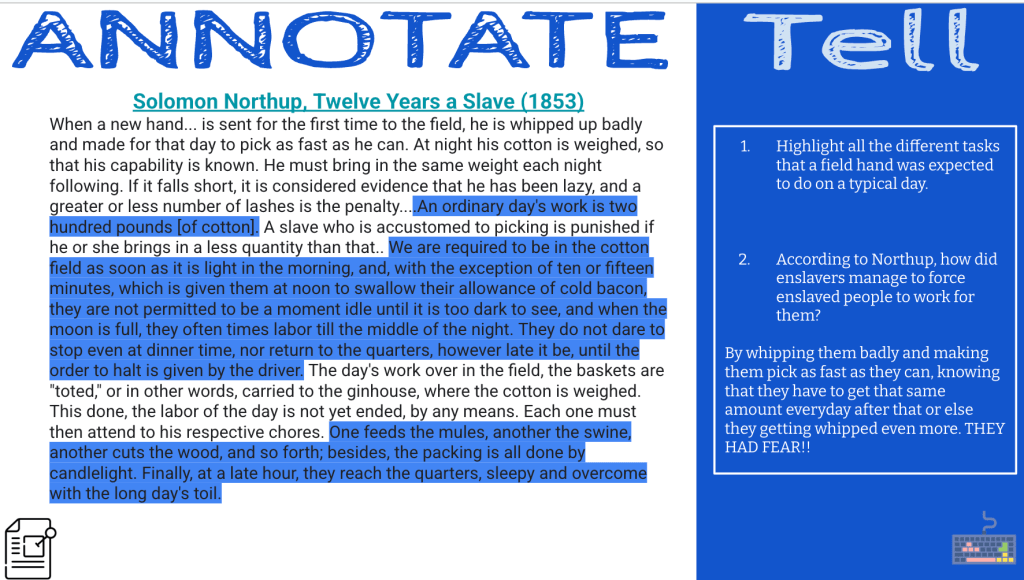

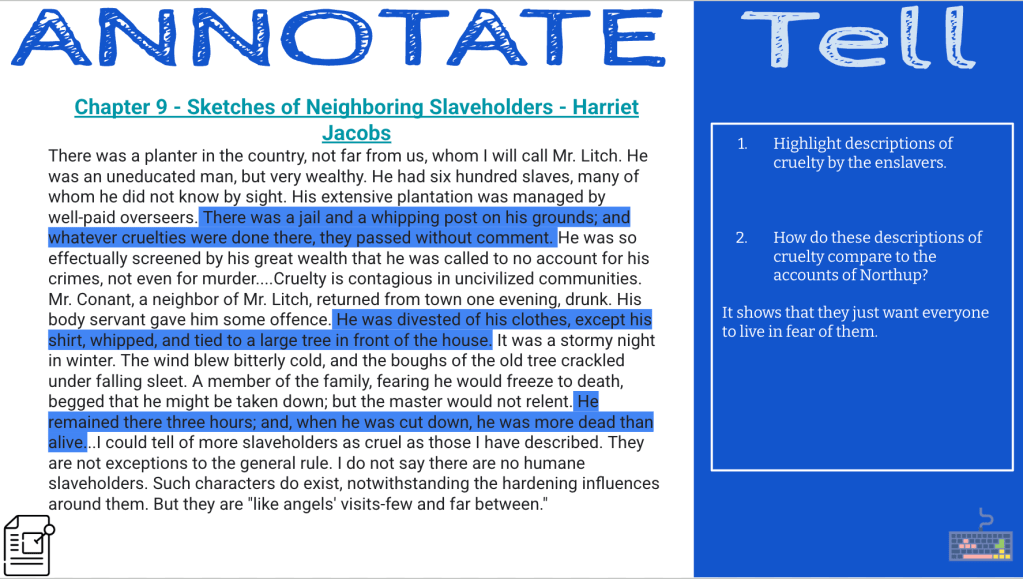

Annotate & Tell

After that, we moved into Annotate and Tell with two powerful excerpts:

- Solomon Northup from Twelve Years a Slave

- Harriet Jacobs from Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

We started with short background blurbs so students knew who these people were and why their stories mattered. Then we read each passage together, pausing to highlight key phrases and answer focused questions.

Northup described long days in the field, being forced to pick 200 pounds of cotton, being punished if you fell short, and chores that lasted well into the night. Jacobs described the cruelty and control that came with wealth—enslavers who tortured without consequence and normalized abuse.

Thick Slide: Be the Abolitionist

Then it was time to apply what they learned. Students created a Thick Slide from the point of view of an abolitionist trying to convince others that slavery must end. Their slide had to include:

- Three quotes from the readings that exposed the reality of slavery

- An explanation of why those quotes mattered

- One form of resistance from the EdPuzzle and why it was important

- A Human Spotlight featuring Harriet Jacobs, Solomon Northup, or someone from the video

- A picture and a short caption telling that person’s story—what they saw, suffered, or stood for

Some students picked quotes that showed the physical brutality. Others focused on how people kept resisting anyway. Their captions were sharp, and a few were honestly emotional. They weren’t just checking boxes—they were making a case.

Teaching the AI Workflow

After they built their slides, I walked them through a quick Chromebook skill:

Ctrl + Shift + Window Switcher = screenshot tool.

Then I showed them how to upload that screenshot into a MagicSchool chatbot I had set up. I modeled how to ask for specific feedback. As I always say, “If you give the AI tool crappy prompts, you’re going to get crap back.”

The whole point was to show them how to use AI after the thinking is done—to reflect, revise, and improve. Not to let AI do it all for them.

Word Wall Review

To wrap everything up, we did a drag-and-drop word wall. Students sorted terms and ideas between North and South—factory, agriculture, slavery, resistance, cotton, railroads, canals, unions, etc. It tied together everything we’ve covered the last two weeks in one quick review. Fast, visual, and a good reset after a deep few days.

Truth With Sprinkles

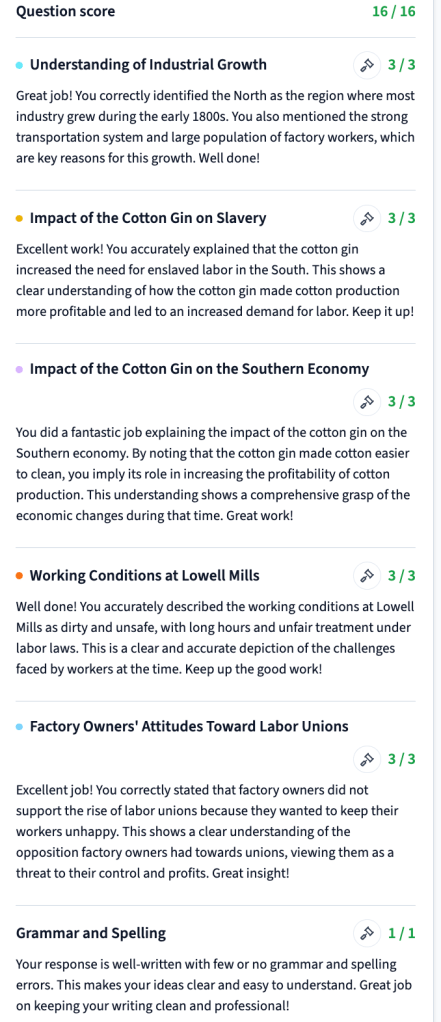

On Friday, I wanted something new for retrieval practice. I began class with a Class Companion – but with a twist!

I had AI create 2 paragraphs with 4 historical errors. Here is what AI came up with:

In the early 1800s, the United States began to shift from farming to factory work. Most industry grew in the South because of its strong transportation system and large population of factory workers. One major invention that helped speed up this progress was the cotton gin. Created by Eli Whitney, this machine made cotton easier to clean and reduced the need for enslaved labor in the South.

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, young women flocked to places like Lowell Mills for clean and safe factory jobs. They worked short hours and were treated fairly under new labor laws. Many factory owners supported the rise of labor unions because they wanted to keep their workers happy. These early unions helped workers demand better conditions with the full support of the people in charge.

I called it “Truth with Sprinkles” – sprinkles of fiction, that is! I brought sprinkled donuts for my 1st period because they worked so damn hard on the state test. It was unbelievable. They wrote their hearts out and gave it everything they had – it was awesome.

So, as they were eating their donuts (some with chocolate frosting and sprinkles) they were finding the sprinkles of fiction in the paragraphs. They were historical detectives.

I set up the Class Companion for only 1 submission – I didn’t want them submitting right away and trying to get the answers. They were discussing, analyzing, and acting as historical detectives fixing the errors. This was an awesome retrieval practice. Class Companion gave them great feedback on each error they tried to correct – it worked out so well!