When I think of teaching the Early Republic, I think about political parties, presidential decisions, and how those decisions shaped the federal government. I think about how the first five presidents kept us out of wars, expanded federal power, and navigated political tensions. I think about how political parties influenced those choices and how the nation evolved under their leadership. But this damn textbook has other plans.

Instead of keeping the focus on political parties, foreign policy, and domestic growth, it randomly throws in sectionalism, the Missouri Compromise, the Industrial Revolution, and some random westward expansion facts—all jammed into two weeks. It’s way too much, and it makes no sense. This is the Early Republic, not a scattershot of everything that happened between 1800 and 1825.

Then Friday rolled around, and we hit the common assessment from the textbook—a test that somehow completely ignores the Monroe Doctrine but includes a question asking students to identify three battles from the War of 1812. Who cares?! It’s not even an important part of the unit.

But I digress.

So, with all that, we kicked off Monday learning about growing sectionalism after the War of 1812. SMH.

Monday – War of 1812 Rack and Stack

Tuesday – Industrial Revolution

Monday

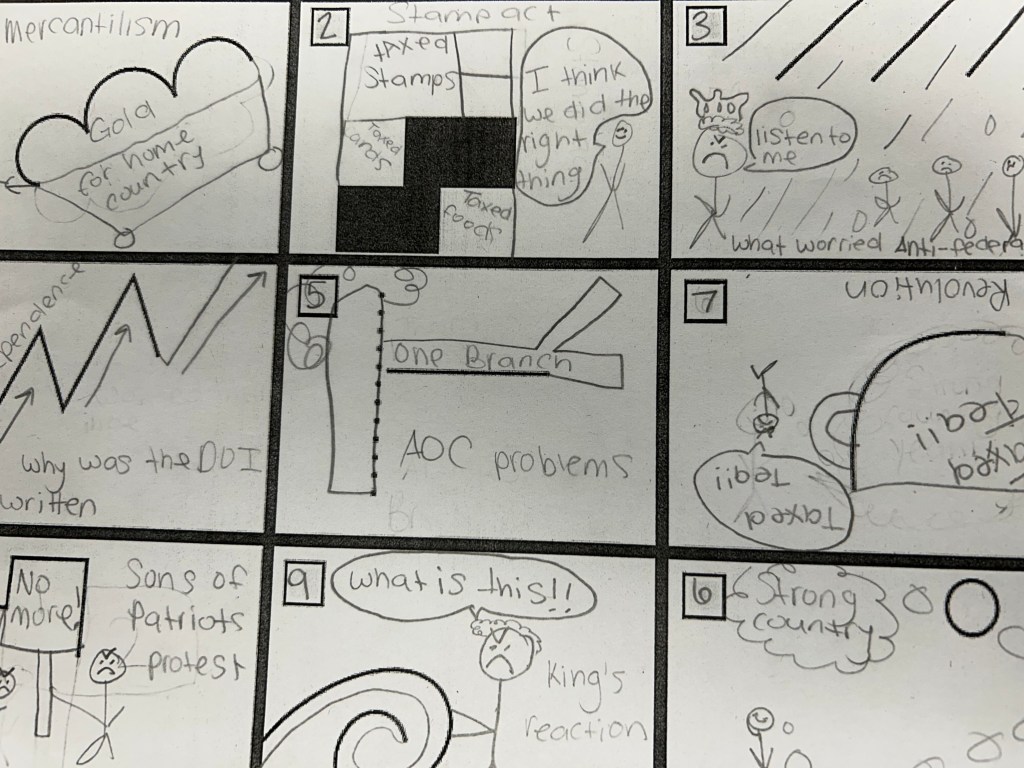

We kicked off Monday with a Content Compactor that acted as a quick review of the causes of the War of 1812. This got students thinking about the political, economic, and regional tensions that led to the war while allowing them to summarize key ideas concisely—an essential skill as we transitioned into the concept of sectionalism.

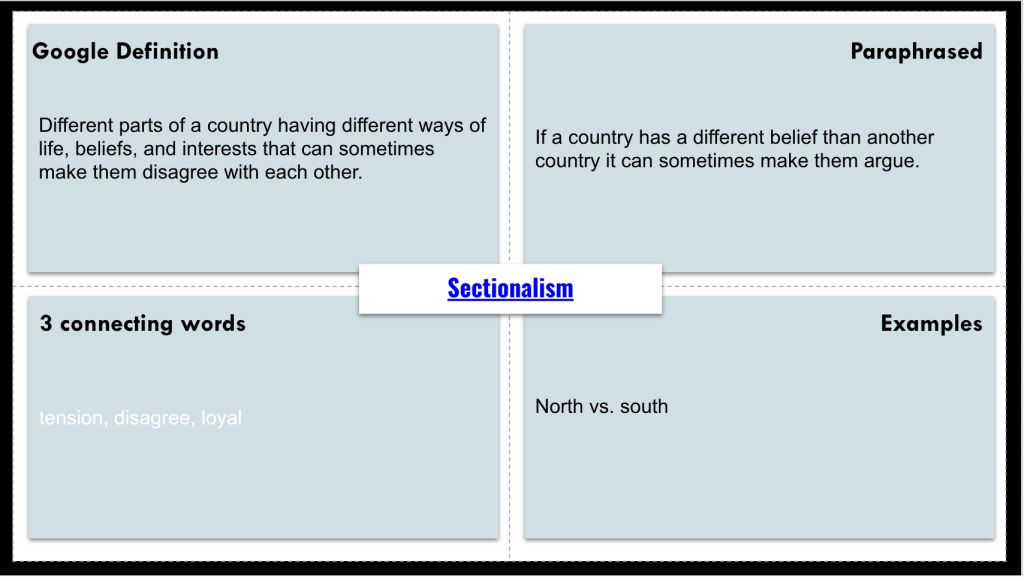

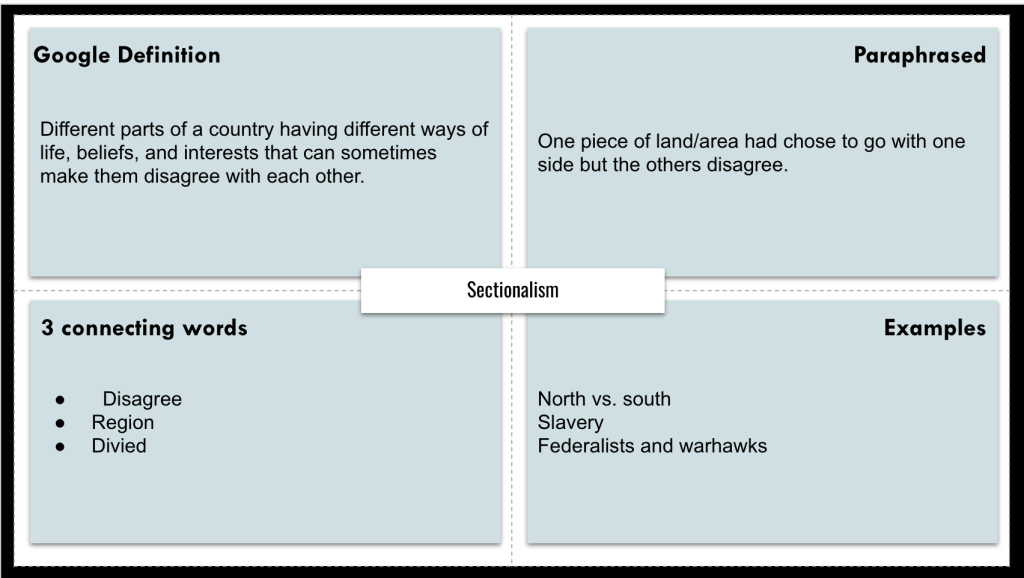

Frayer Model: Defining Sectionalism

Next, we tackled sectionalism with a Frayer Model. Students defined the term, provided examples and non-examples, and listed key characteristics. The goal was to help students see sectionalism not just as a word, but as a major force that would shape U.S. history for decades. This activity ensured that students grasped the economic, political, and social divisions developing between regions of the country.

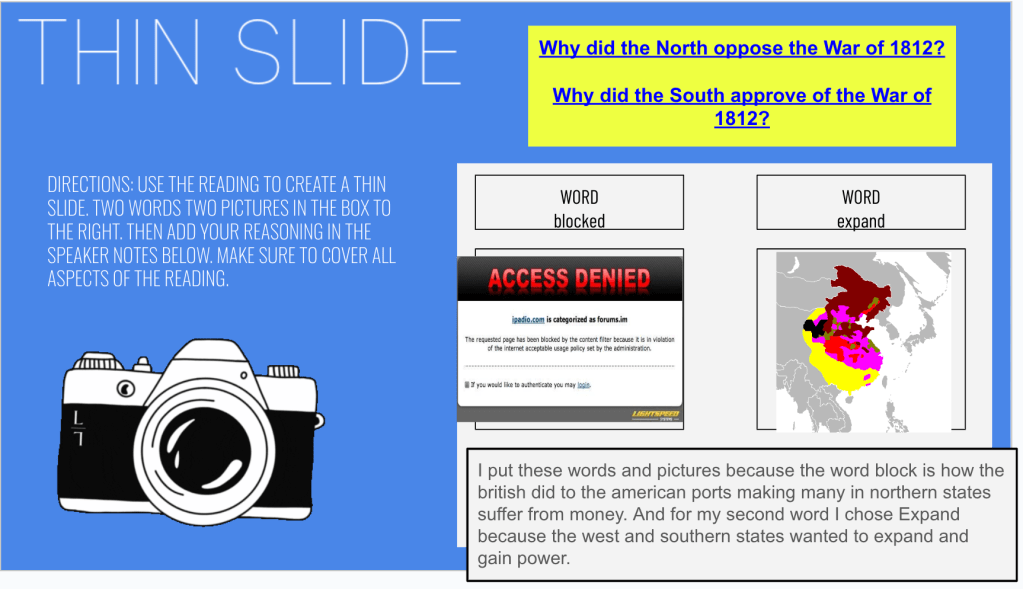

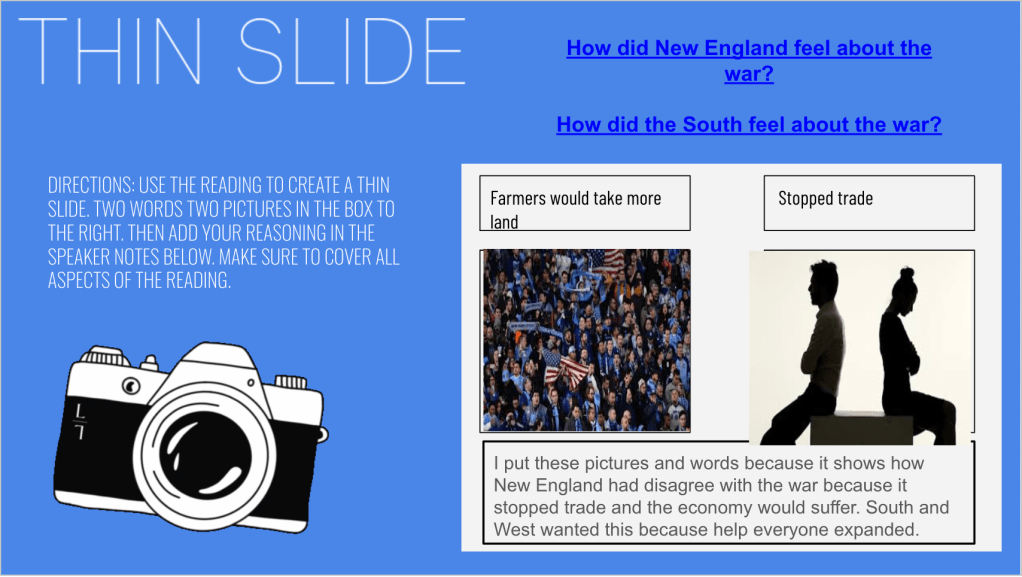

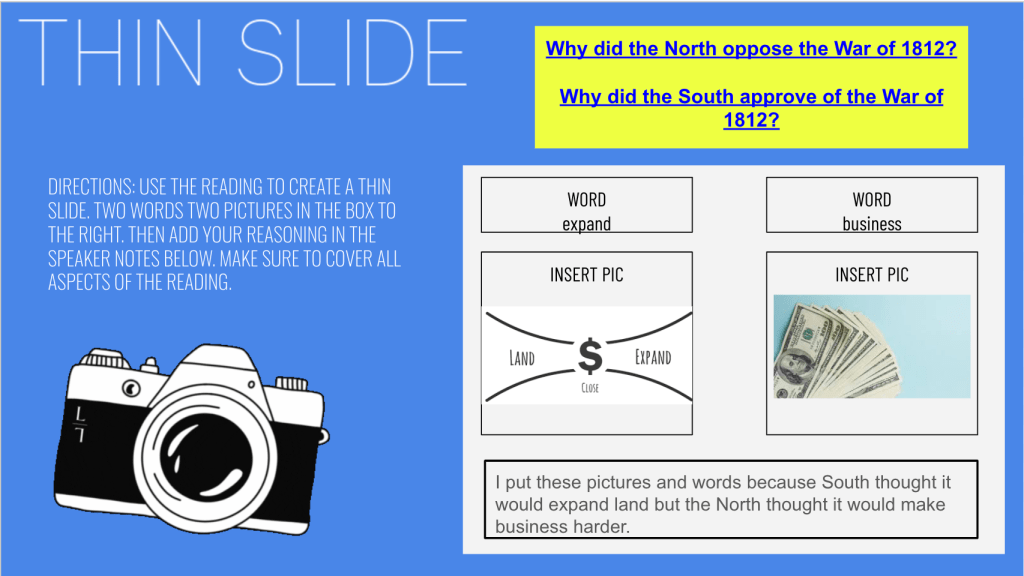

Thin Slides: Visualizing Sectionalism

Once students had a working definition, they moved into a Thin Slides activity. Using a short reading on sectionalism, they selected two words and two images that best represented how sectionalism grew after the War of 1812. In the speaker notes, they explained their choices, addressing:

- Why did the North oppose the war?

- Why did the South support it?

- How did economic and political differences lead to sectionalism?

This was a quick, low-stakes way for students to process how sectional tensions formed and why they mattered.

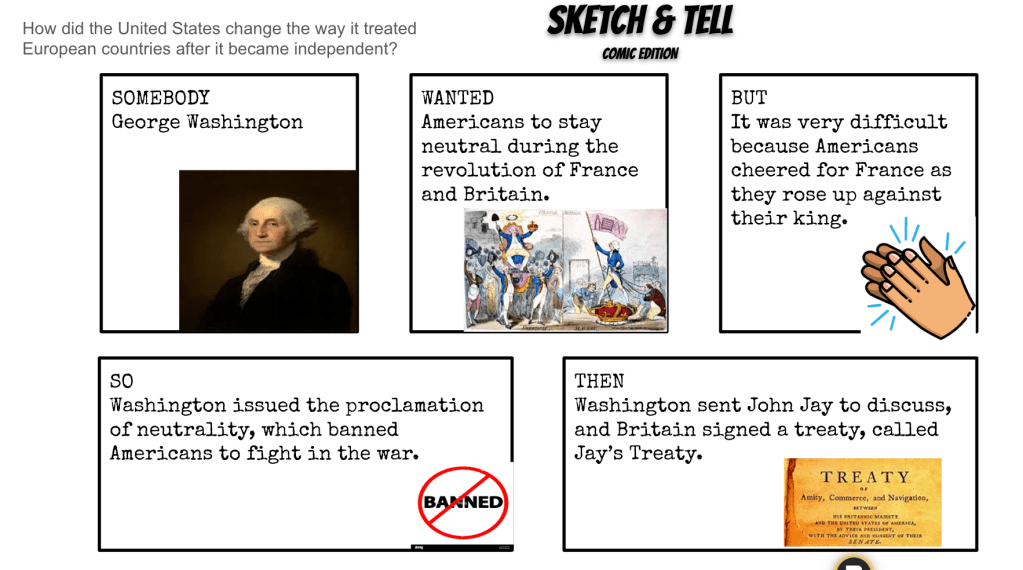

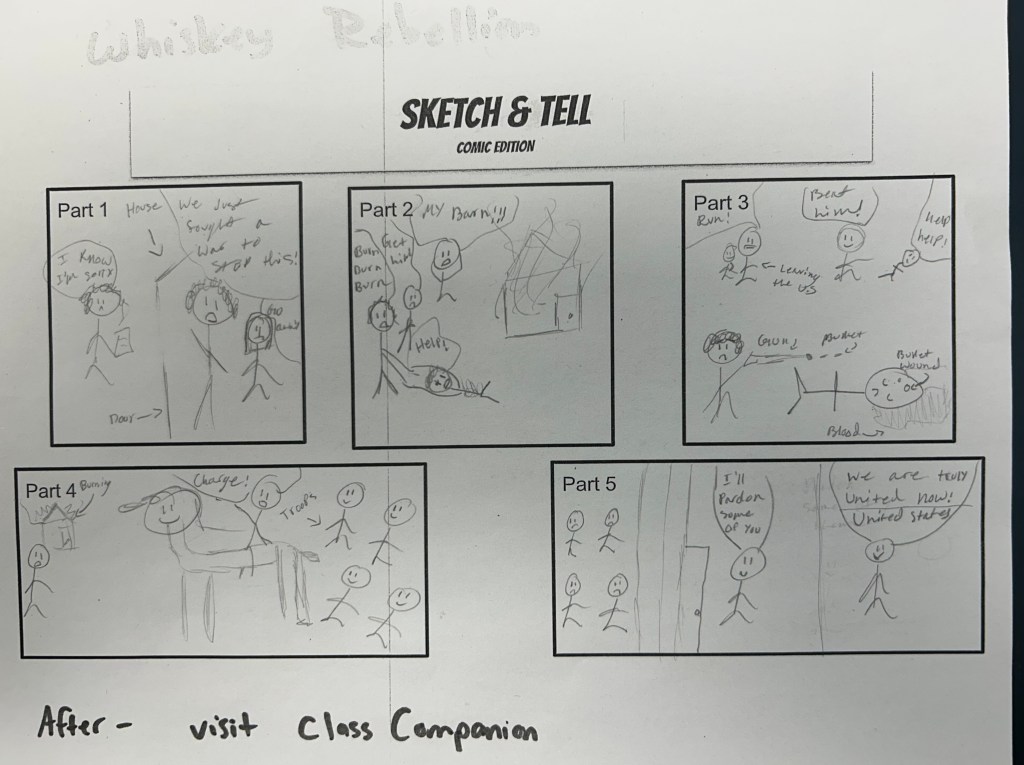

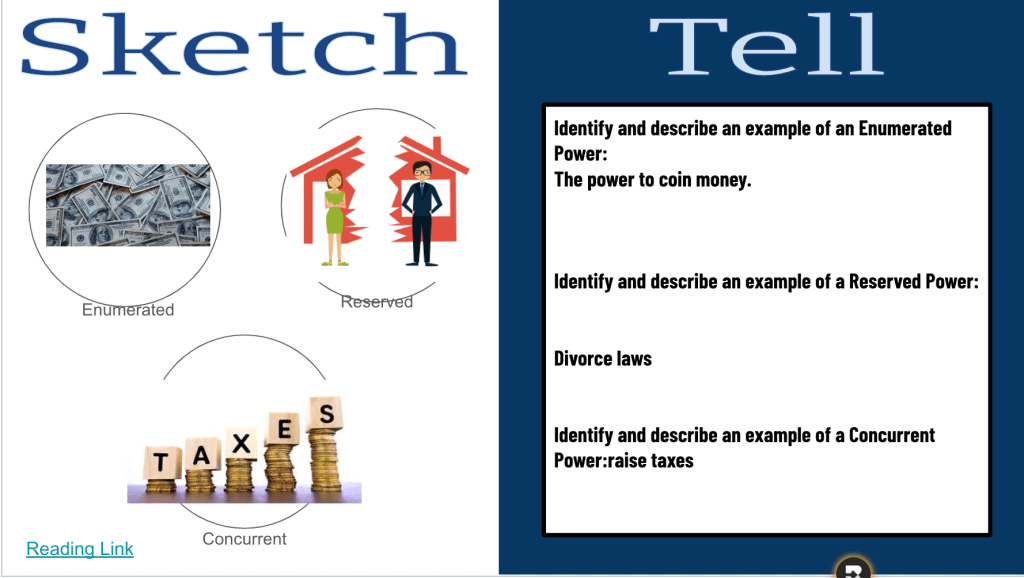

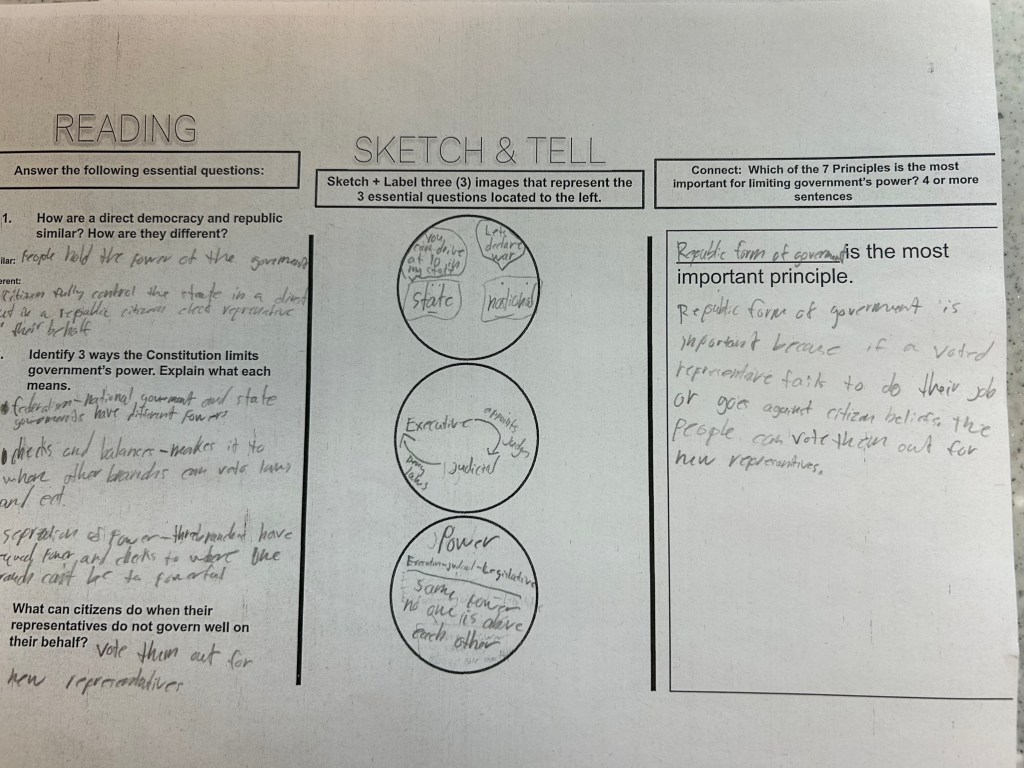

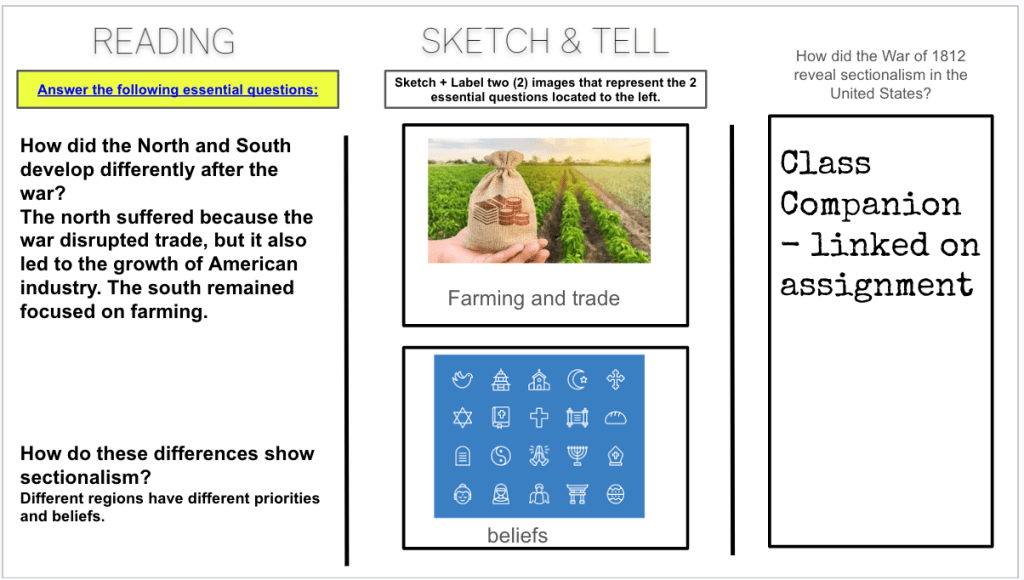

Sketch & Tell: Answering Essential Questions

Students then tackled three essential questions through a Sketch & Tell activity:

1️⃣ How did the North and South develop differently after the war?

2️⃣ How did these differences contribute to sectionalism?

3️⃣ How did the War of 1812 reveal sectionalism in the U.S.?

They created two labeled sketches that visually represented their answers, reinforcing how regional differences in economy, industry, and policy contributed to rising sectional tensions.

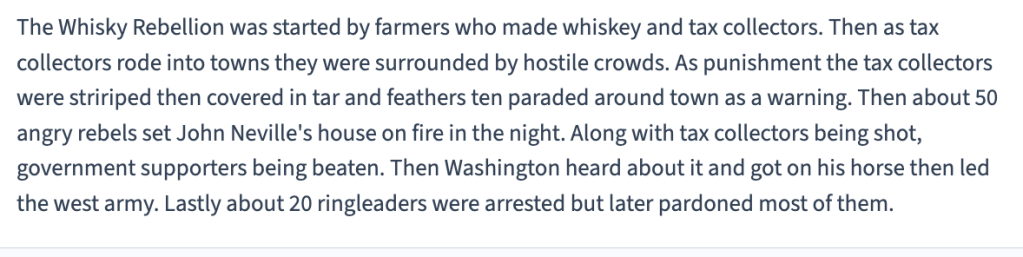

Class Companion: Writing About Sectionalism

To wrap it up, students used Class Companion to answer the question:

💡 How did the War of 1812 reveal sectionalism after the war?

This allowed students to take their thoughts from their sketches and turn them into a structured response with real-time AI feedback. Since some students needed more time to refine their writing, we carried this over into Tuesday, giving them an opportunity to perfect their responses and ensure they fully understood sectionalism’s impact.

Why This Works

- Content Compactor helped students refresh prior knowledge in a concise, engaging way.

- Frayer Model ensured students developed a strong conceptual foundation before moving forward.

- Thin Slides encouraged visual learning and synthesis of ideas.

- Sketch & Tell helped students explain complex historical trends in a creative, student-centered way.

- Class Companion allowed students to organize their thoughts in writing with immediate, personalized feedback.

Instead of just reading about sectionalism, students were building their understanding step by step, using visual, discussion-based, and writing activities to make the concept stick.

Tuesday & Wednesday

We started Tuesday by finishing up Class Companion responses from Monday on how the War of 1812 revealed sectionalism. Once students submitted their final responses, we pivoted to the Industrial Revolution—a topic that the unit test oddly prioritizes with fill-in-the-blank questions on patents, corporations, and capitalism, but barely acknowledges the Monroe Doctrine or foreign policy under the early presidents. Because that makes total sense.

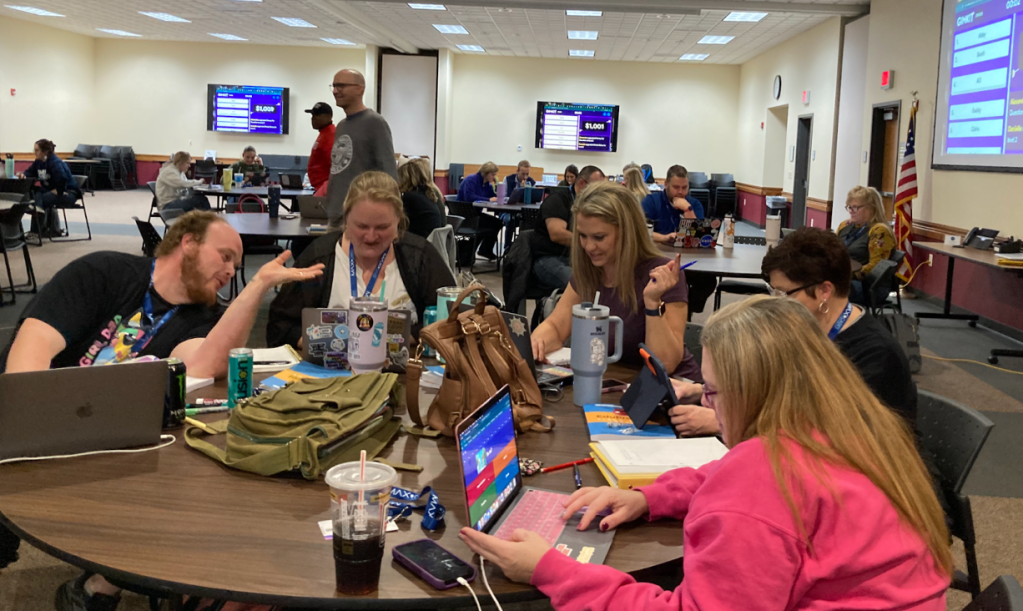

Gimkit Fast & Curious: Industrial Revolution Vocab

Since the test focuses so much on random economic terms, we ran a Gimkit Fast & Curious with key Industrial Revolution vocabulary—words like patent, corporation, free enterprise, and capitalism. First round: class averages were pretty bad. After giving a quick mini-lesson on the most-missed words, we ran the Gimkit again, and scores jumped up significantly.

To lock in the most commonly missed terms, we followed up with Frayer Models for:

🔹 Patent

🔹 Corporation

🔹 Free Enterprise

Reading, Videos & Thick Slides

After breaking down the vocabulary, students read about key innovations of the Industrial Revolution—factories, mechanization, interchangeable parts, and yes, the cotton gin (because clearly, that fits into an Early Republic unit 🤦♂️).

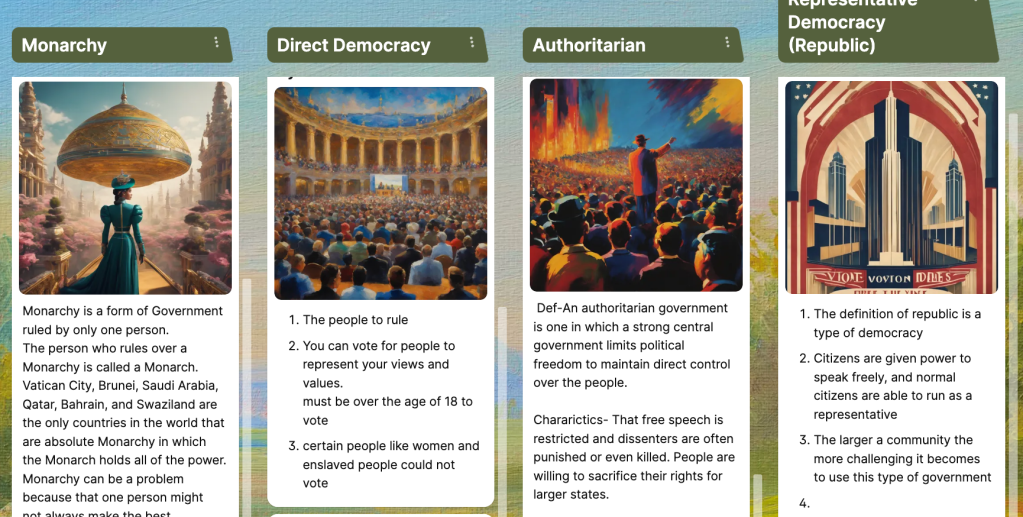

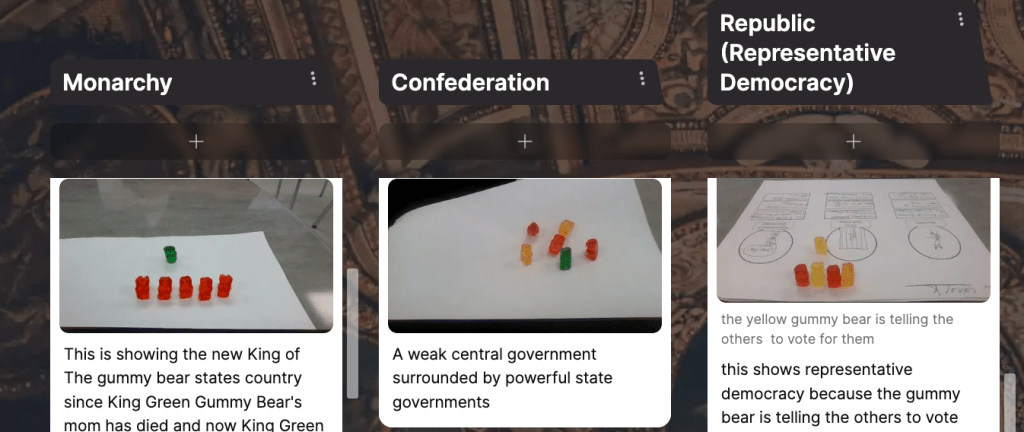

To help process the reading, students worked on Thick Slides focused on four ways the Industrial Revolution transformed America. They had to:

✅ List four key impacts

✅ Find an image to represent industrialization

✅ Compare the North and South’s role in industrialization

Why This Works

- Gimkit Fast & Curious ensured students got multiple reps with essential vocabulary.

- Thick Slides helped synthesize and apply learning, rather than just memorizing random terms.

- Multiple formats (reading, videos, notes, discussion, and visuals) ensured everyone had a way to engage with the content.

Even though this topic was awkwardly shoved into the unit, we made it work in a way that actually helped students understand and retain the material—instead of just cramming information for a test.

Thursday

With the unit test coming up, I wanted to make sure students had multiple opportunities to review key concepts in an engaging and structured way. Enter Brain, Book, Buddy, Boss—one of my favorite review strategies because it reinforces retrieval practice, collaboration, and teacher-guided clarification all in one lesson.

Step 1: Brain (Independent Recall)

Students received the review sheet (matching terms, short answer questions, and key concepts from The Early Republic). Before looking at any resources, they went through the entire review sheet independently, answering as many questions as they could from memory.

The goal? Get a sense of what they already know.

Some students flew through it, while others stared blankly at the paper. That’s the beauty of this step—it exposes strengths and gaps immediately.

Step 2: Book (Reference-Based Learning)

Next, students used their notes, textbooks, and classwork to fill in missing answers and correct any mistakes. This phase is where light bulbs start going off as students piece together information they’ve seen throughout the unit.

Of course, this is also where they discover just how terribly worded some of these test questions are.

For example, here’s an actual test question:

“What were some effects of the Alien and Sedition Acts?”

A. The policy of nullification became largely discredited.

B. The French stopped attacking U.S. ships.

C. Fewer people immigrated to the United States from Europe.

D. The principle of states’ rights gained public support.

This question assumes a level of vocabulary knowledge that most 8th graders simply don’t have. The wording is vague enough to confuse even students who understand the Alien and Sedition Acts. What 8th grader uses discredited in conversation?

Step 3: Buddy (Peer Discussion & Comparison)

After self-correcting with their books, students paired up to compare answers and discuss any remaining gaps. If they disagreed on an answer, they had to explain their reasoning to each other.

These conversations were gold—students challenging each other, correcting mistakes, and realizing where they were off-track. They got into heated debates over Federalist vs. Republican beliefs and the importance of Marbury v. Madison. This step solidified a lot of key concepts.

Step 4: Boss (Teacher Q&A)

For the final step, I opened the floor for questions. Students could ask me about anything still unclear—but with a catch:

They only had 8 minutes.

Once the timer hit zero, I was done answering. This forces students to prioritize their questions and keeps the review focused and efficient.

Why This Works

- Brain (independent recall) activates retrieval practice.

- Book helps reinforce accuracy and self-correction.

- Buddy provides peer discussion and clarification.

- Boss allows for focused teacher intervention in a structured way.

By the end of class, students had worked through misconceptions, clarified their understanding, and felt more confident about the material. It was one of the best review strategies for this test, and it reinforced just how flawed some of the test’s wording really was.

Friday: Test Day

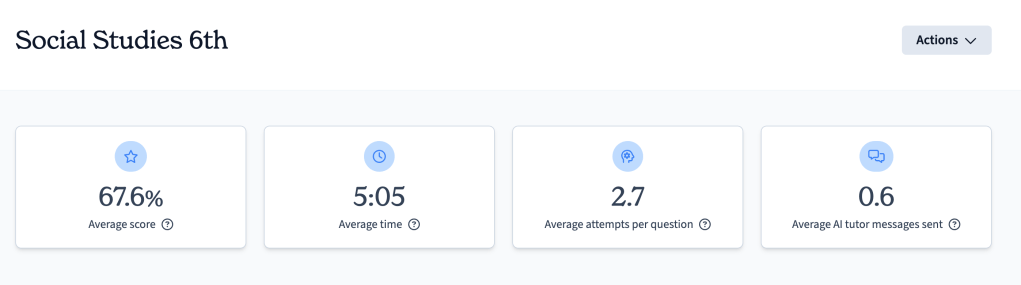

Friday was test day, and I had everything set up on Class Companion for the short answer questions, while using McGraw Hill’s testing program for the multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank sections.

One of the fill-in-the-blank questions asked about the beliefs of Democratic-Republicans. Most students simply typed “Republicans”, which is a reasonable answer considering the textbook even calls them that at times.

But McGraw Hill marked it wrong because they didn’t type the answer exactly as programmed: “Democratic-Republicans, Republicans”. I wish I were making this up.

So now, instead of assessing whether students actually understood the beliefs of the party, we were stuck in a battle of formatting.

Class Companion: At Least It Scored Correctly

For the short answer responses, Class Companion scored and provided feedback, but students only had one attempt—no revisions, just one shot. At least it evaluated their responses based on content rather than formatting nonsense.

I need a damn drink.