This week was all about using EduProtocols to drive deeper thinking, engagement, and writing practice as we explored westward expansion and Manifest Destiny. Instead of just reading from the textbook and answering questions, students worked through activities that encouraged them to generate their own questions, analyze sources, and compare perspectives. We used Fast & Curious to build vocabulary, Wicked Hydra to spark curiosity, Sourcing Parts to break down historical imagery, and MiniReport to develop writing skills with multiple sources. Class Companion provided immediate feedback on their writing, helping them refine their responses. The combination of these strategies helped students interact with history in meaningful ways while reinforcing critical thinking and writing—exactly the kind of skills they need as we approach testing season.

Wednesday – Introduction to Westward Expansion

Thursday – Rack and Stack Manifest Destiny, MiniReport

Friday – WeWillWrite, ShortAnswer

Monday and Tuesday

Monday and Tuesday were all about finishing the Age of Jackson unit and transitioning into what’s next. It wasn’t the most eventful start to the week, but there were some clear takeaways from how students engaged with the material and performed on the final assessment.

Trail of Tears Number Mania

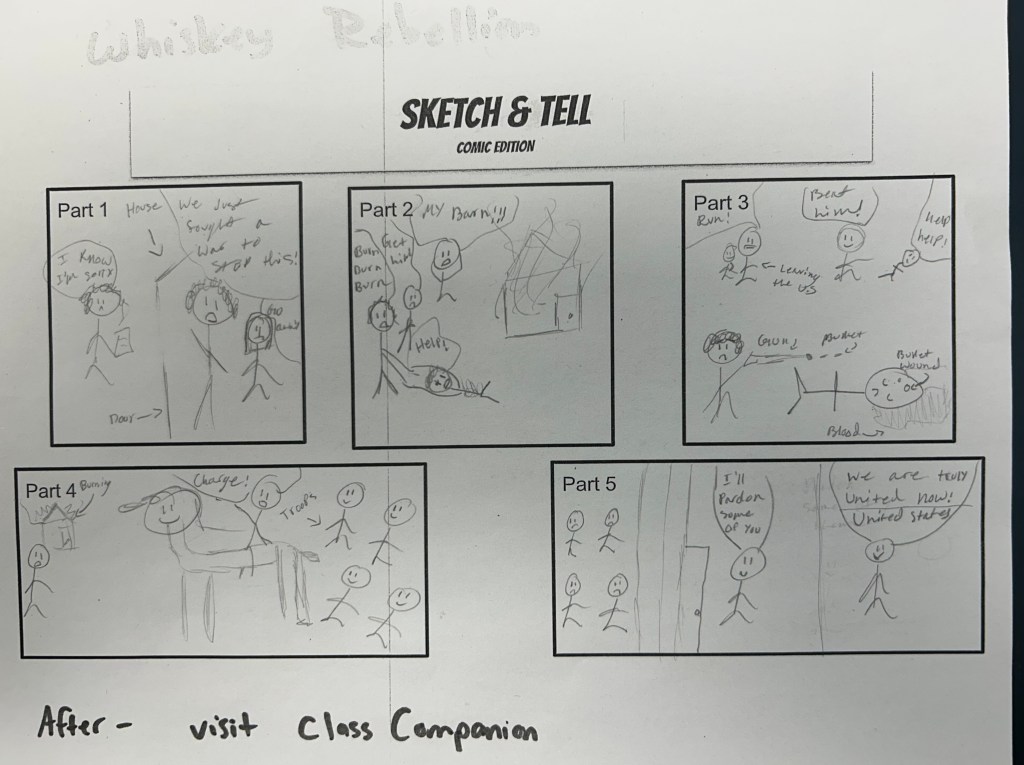

We closed out the unit with a Number Mania activity focused on the Trail of Tears. Students worked to prove this statement correct using four numbers and supporting facts from the reading:

“The Trail Where They Cried was not only a physical journey but also a moment that reshaped Cherokee history, causing loss, suffering, and ultimately rebuilding.”

This strategy forced them to dig into the reading, prioritize key details, and make connections between the numbers and the broader historical context.

Review Day: Where Did Students Struggle?

After Number Mania, we jumped into a self-assessment review where I encouraged students to answer as many questions as possible without looking at their notes first. I wanted to see what truly stuck.

The results were telling:

✅ Strong understanding of Jacksonian Democracy and the Bank War

❌ Struggled with Nullification and Tariffs

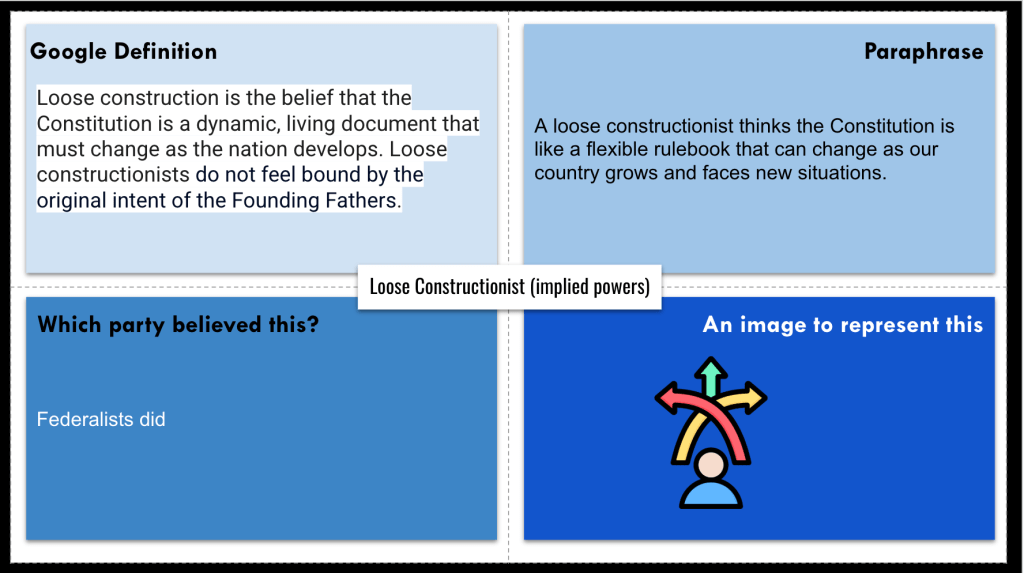

Looking at what worked, the MiniReport EduProtocol (which we used for Jacksonian Democracy and the Bank War) stood out as a clear success. This structured approach to reading, analyzing, and writing about sources helped cement those concepts more effectively than other methods.

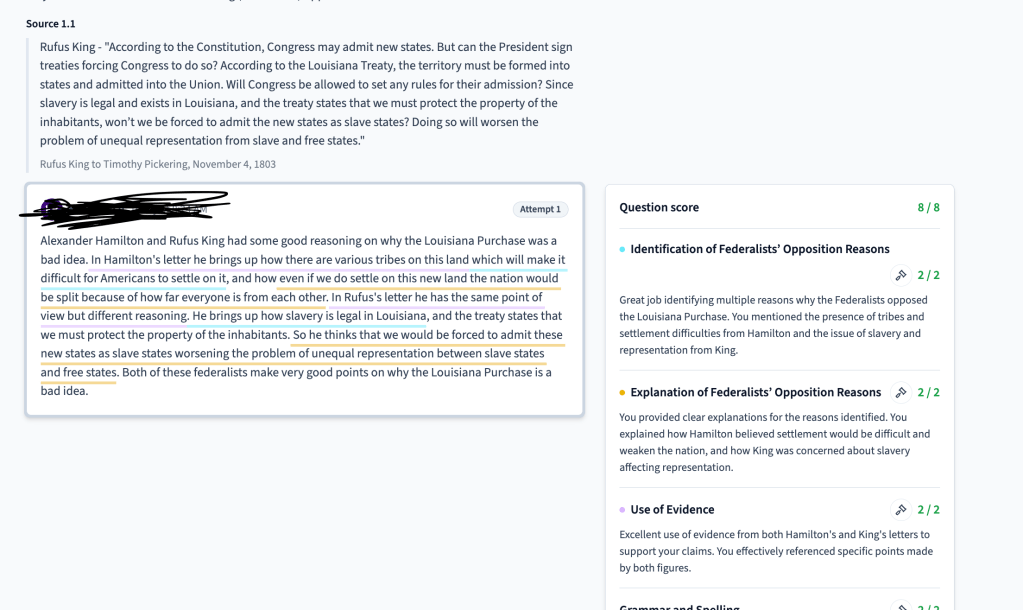

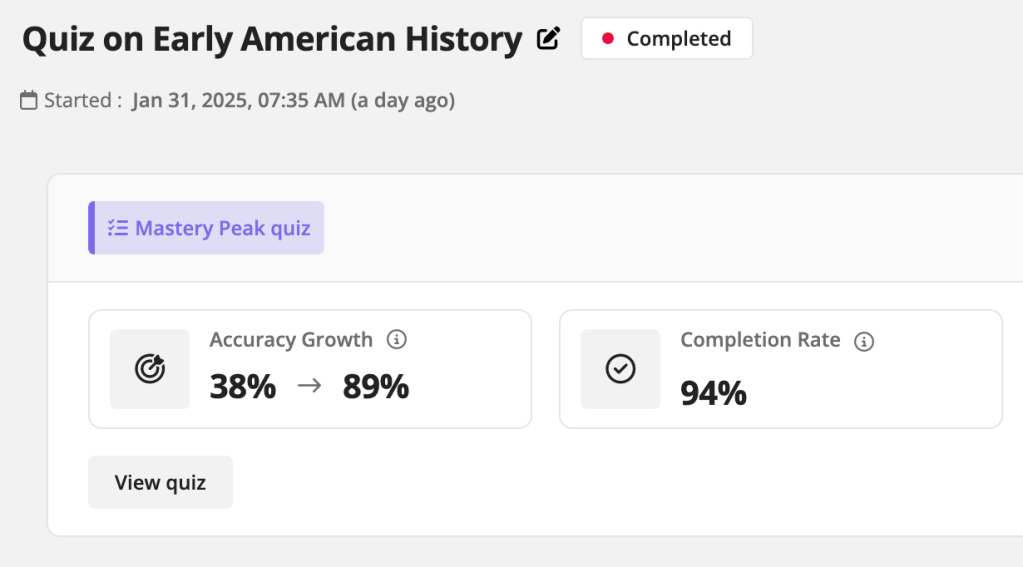

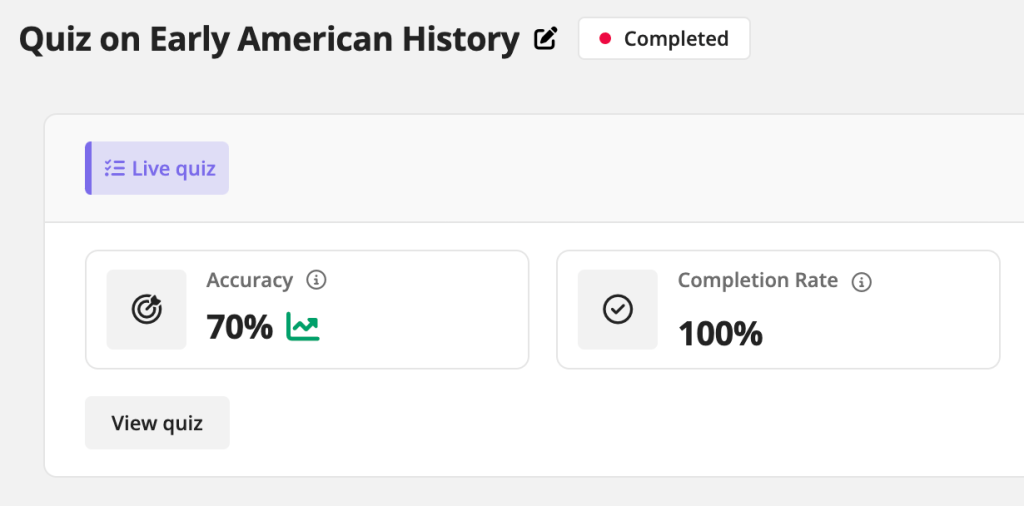

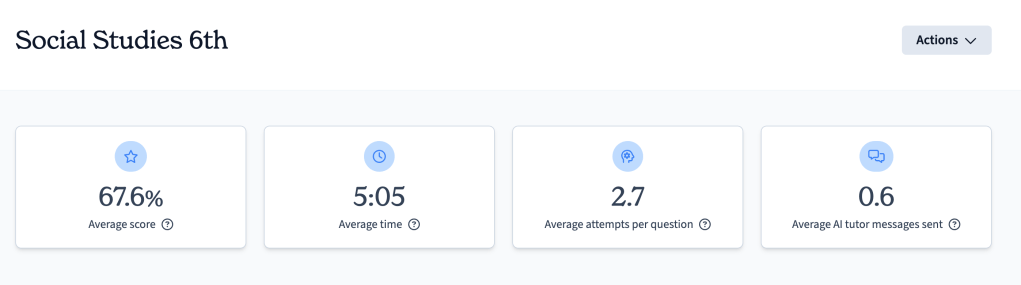

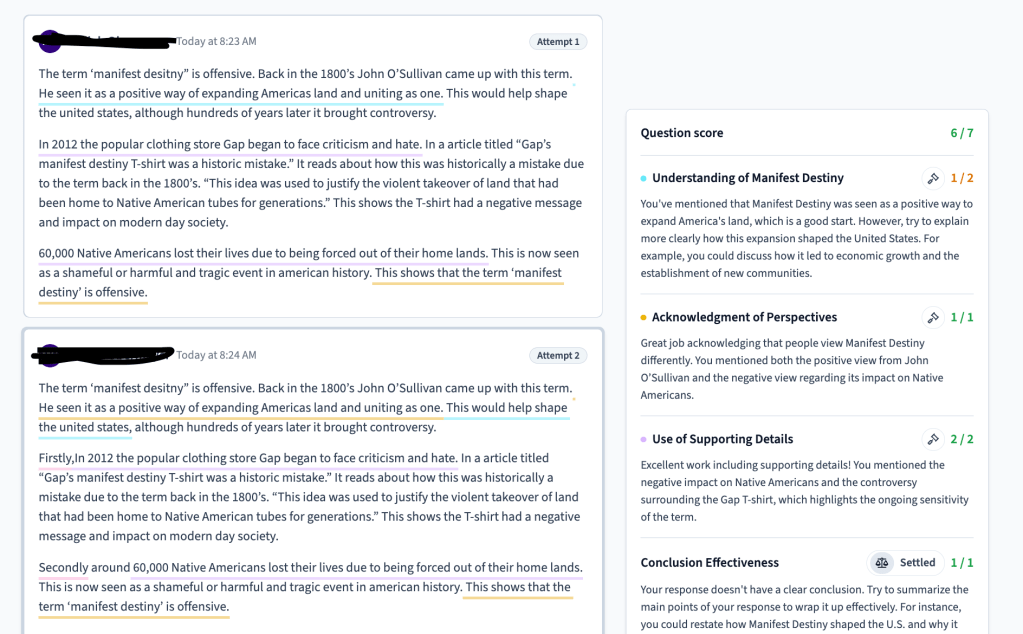

Final Test & Class Companion for Writing

Tuesday was test day. To keep the writing portion meaningful, I had students complete their short-answer responses on Class Companion, giving them two attempts this time. The difference was noticeable—students were reading the feedback, revising their responses, and improving their writing in real-time.

At the end of the test, I tallied up the class averages:

📉 Pre-Assessment Scores: 22%, 19%, 22%, 25%

📈 Final Assessment Scores: 82%, 68%, 76%, 80%

In just five class periods, the gains were solid. I wish I had more time to dive deeper into certain topics, but when you’re locked into a common assessment deadline, you make the most of the time you have. The biggest takeaway? The MiniReport works, Class Companion feedback works, and students rise to the challenge when given the right tools.

Wednesday

This week, I kicked off a mini-unit on Westward Expansion, focusing on the big question: How did Manifest Destiny change America’s map and the lives of different groups of people?

I like to break this unit down into three key areas:

✅ The idea of Manifest Destiny

✅ How the U.S. acquired different territories

✅ The people and groups who moved west

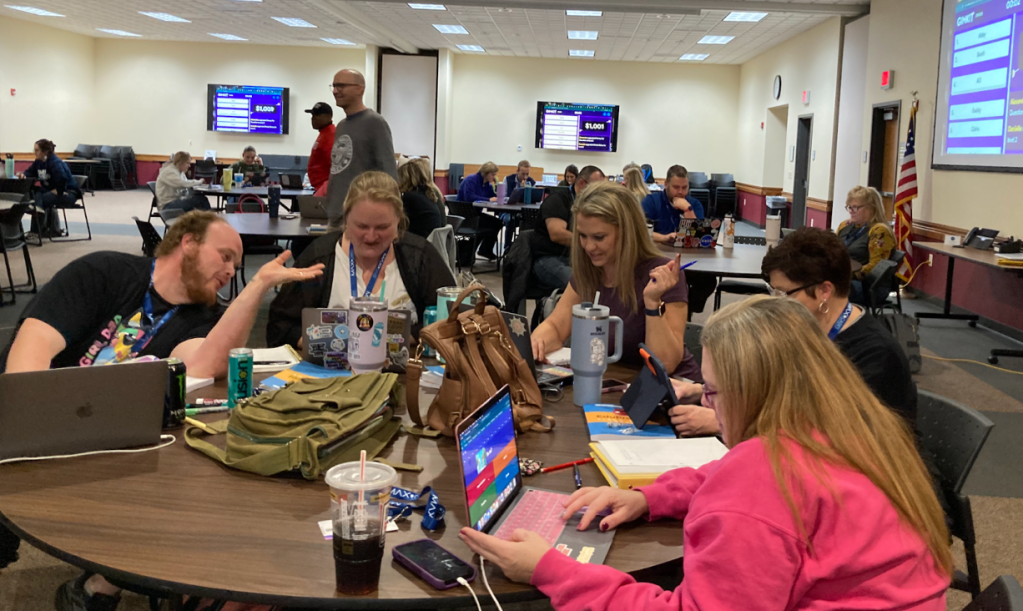

To start, I introduced some key vocabulary with a Gimkit Fast & Curious covering terms like Manifest Destiny, expansion, territory, annexation, and more. We ran the Gimkit for 3 minutes, I gave quick feedback, and then we ran it again for another 3 minutes. With students now having some familiarity with the key terms, it was time to move into The Great American Race—a fast-paced, high-engagement EduProtocol that reinforces key concepts through collaboration and research.

How I Run The Great American Race

A few teachers have asked me how I set this up, so here’s my process:

1️⃣ Identify the Key Topics

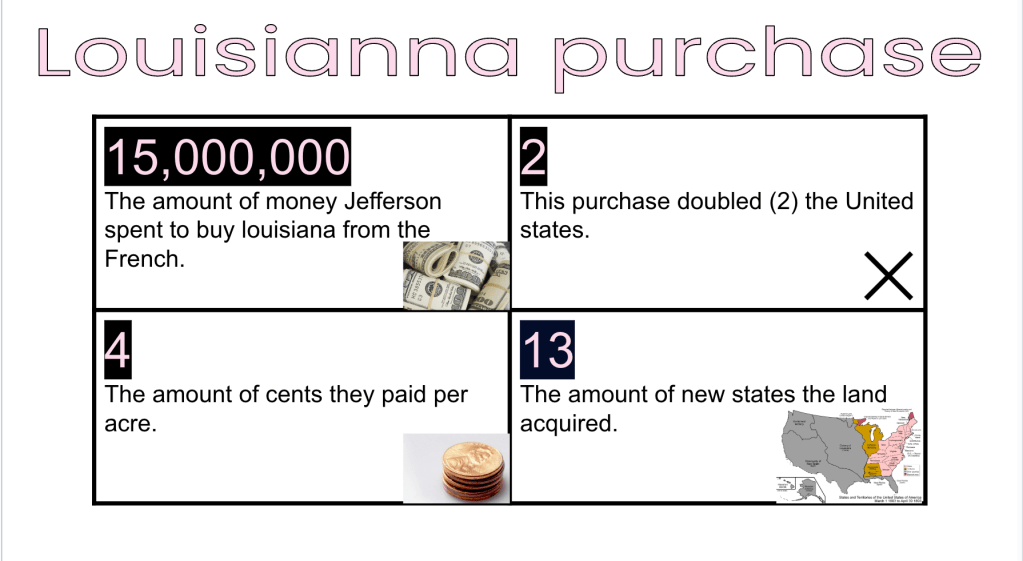

- I chose 13 major terms from the unit, including the Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark, James K. Polk, and Manifest Destiny.

- Since I had 26 students, they paired up, with each pair responsible for one term.

2️⃣ Use AI to Generate Content

- I’ve been using AI to create 4-5 sentence explanations for each term, which students can pull clues from.

- Each explanation is labeled with a number corresponding to its term.

3️⃣ Set Up the Activity

- I copy and paste the AI-generated explanations into a Google Doc, print them out, and cut them into individual slips for students.

- Each pair receives a slip and has 3-4 minutes to create a response on Padlet using the timeline format.

4️⃣ Creating the Clues

- On their Padlet post, students enter their term’s number in the subject line.

- They write 3 clues and add a related image.

- This should take 3-4 minutes, but my students usually take about 6-8 minutes.

5️⃣ Approving and Freezing Posts

- I set Padlet so that I approve all posts before they go live.

- Once time is up, I approve the posts, and students are ready to start the race.

- Why I freeze the Padlet: This prevents students from copying and pasting answers directly into Google. They have to use key terms and context clues to research.

6️⃣ The Race Begins!

- Students work with their partner, number their paper 1-13, and get 15 minutes to identify as many terms as possible using the clues from their classmates’ posts.

- They can use their notes, their knowledge, and Google—just not copy-paste answers directly.

- When time is up, we go over the answers and discuss any misconceptions.

Padlet makes this whole process smooth, especially with the timeline format, which keeps everything organized. The students love the competitive element, and I love that they’re engaged and thinking critically.

Wrapping Up with Big-Picture Questions

To close the lesson, I handed out an introductory reading on Westward Expansion. On the back, I included three deeper-thinking questions to get them thinking beyond just dates and facts:

📌 Evaluating Perspectives: How might an American settler and an Indigenous person have viewed westward expansion differently?

📌 Connecting to Today: Do you think Manifest Destiny still influences how Americans view expansion and progress today? Why or why not?

📌 Comparing Motivations: What were the different reasons people moved westward, and how did those reasons create tensions among settlers, Native Americans, and the U.S. government?

Students had 10 minutes to read and answer the questions. This served as a preview for deeper discussions and activities later in the unit.

Thursday

Fast & Curious: Building Vocabulary

We started class with a Fast & Curious using Gimkit to review key vocabulary related to westward expansion. Students played for three minutes, received feedback, and then played again to reinforce terms like Manifest Destiny, annexation, expansion, and acquisition. This quick repetition helped them solidify essential vocabulary before moving into deeper analysis.

Wicked Hydra: Generating Questions

Next, we transitioned into a Wicked Hydra using the headline, “Gap’s T-Shirt Was a Historic Mistake.” The goal was to get students asking as many questions as possible about what the headline might mean. Originally, we used Padlet for this, but after accidentally deleting the responses, we switched to paper, and students continued writing down their questions. Some of the best questions that came from this activity included:

- Why would a T-shirt about Manifest Destiny be controversial?

- Who was upset by this, and why?

- What does this headline tell us about how history is remembered?

These questions set the stage for students to engage critically with Manifest Destiny as both a historical event and a modern controversy.

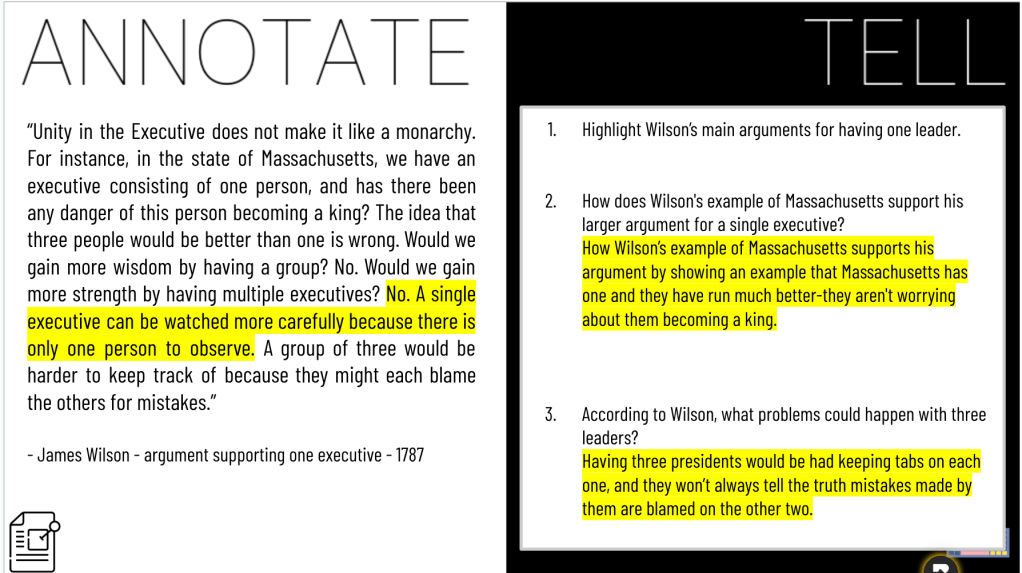

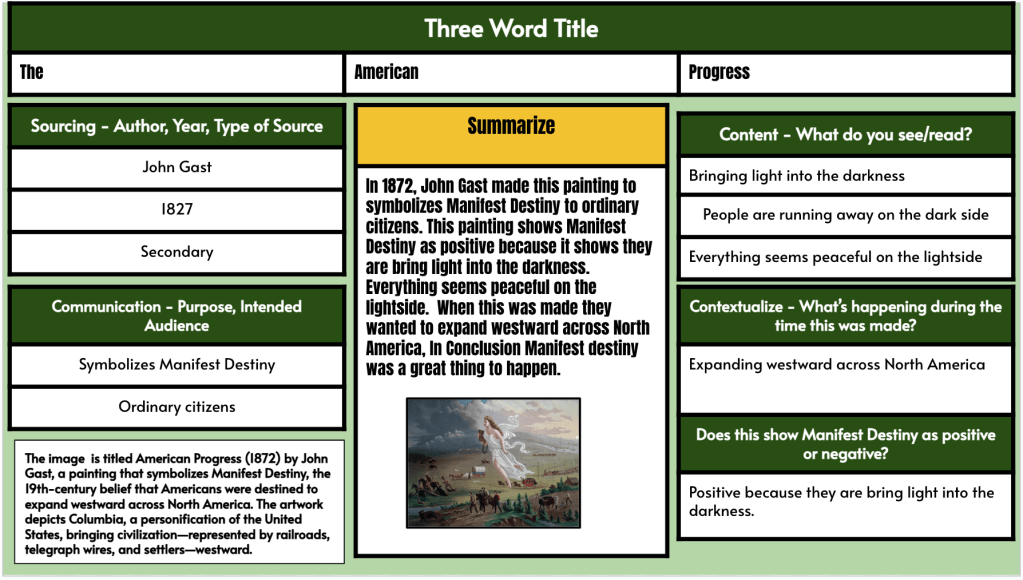

Sourcing Parts: Analyzing “American Progress”

To further analyze the idea of Manifest Destiny, students used the Sourcing Parts protocol to break down the painting American Progress by John Gast. The goal was to help them understand how imagery can be used to justify expansion. They examined the source by identifying who created it, what message was being conveyed, and who was included or left out of the image. The discussion that followed centered on how paintings like this one helped promote the idea of Manifest Destiny as a positive force while ignoring the consequences for Indigenous people and others affected by westward expansion.

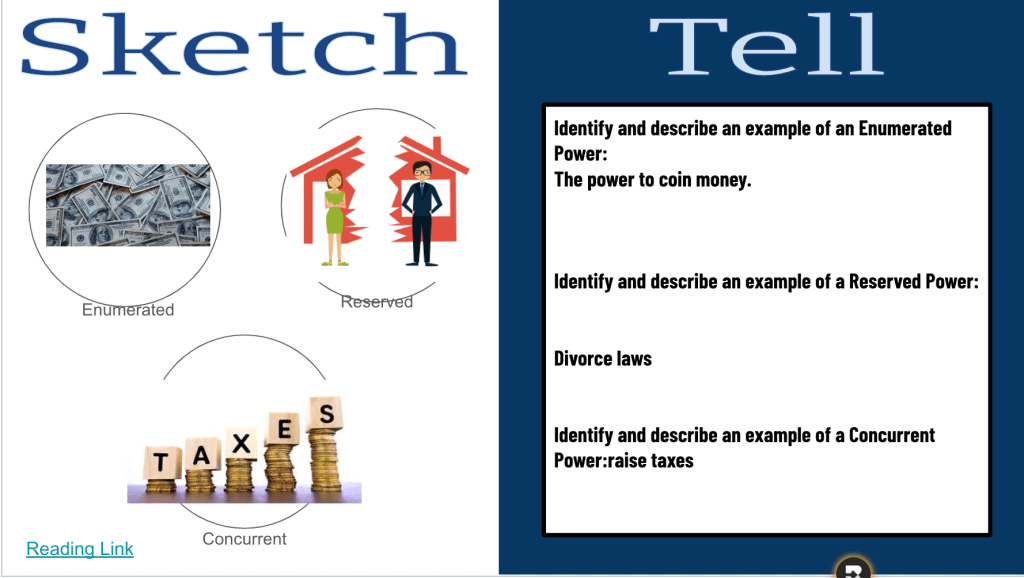

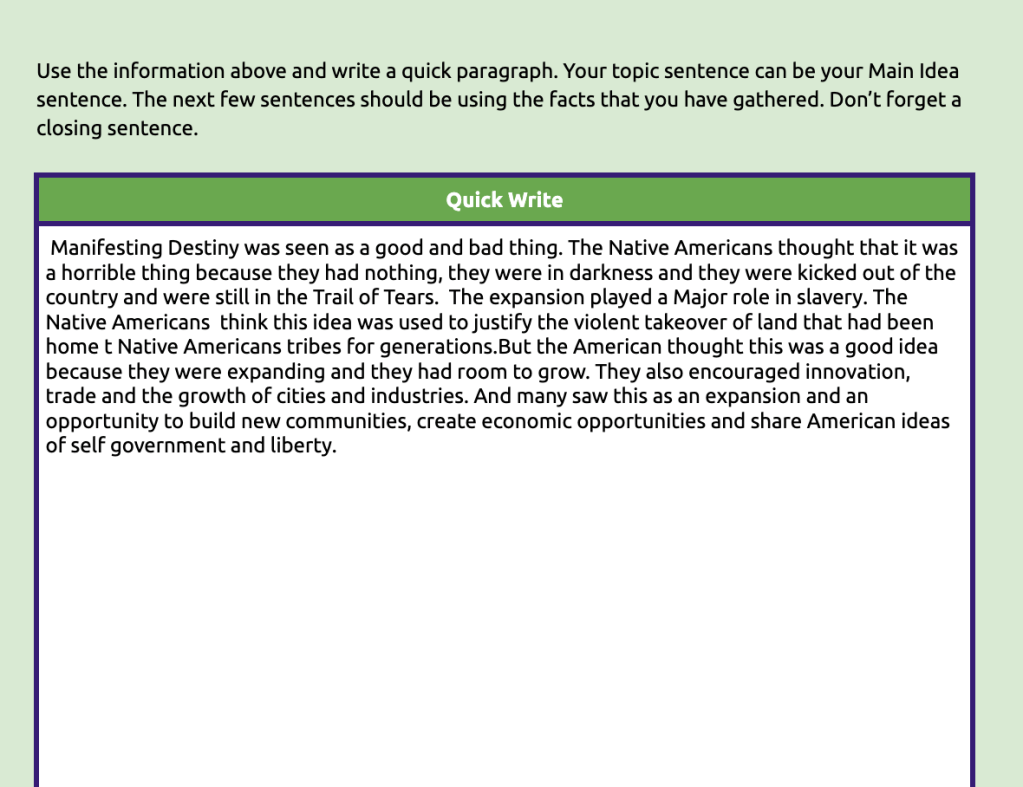

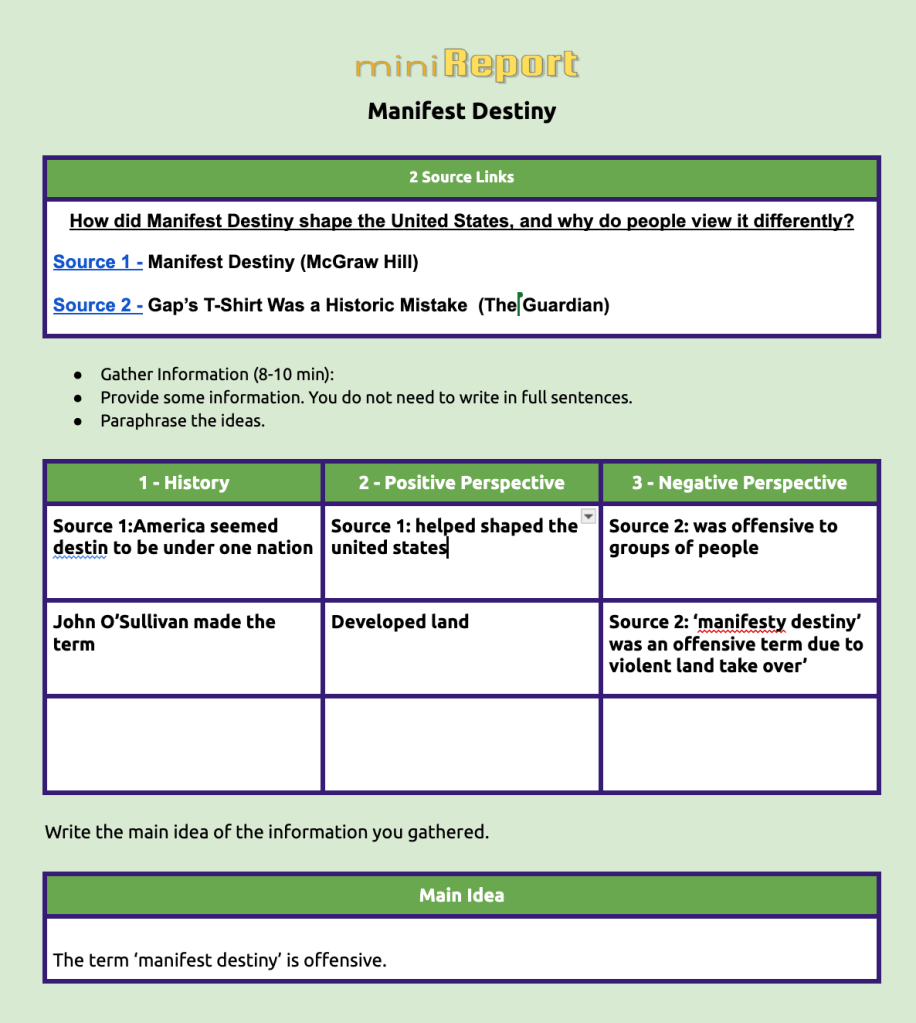

MiniReport: Comparing Perspectives

After this, we moved into a MiniReport comparing two different perspectives on Manifest Destiny. The first source was adapted from the McGraw Hill textbook and explained Manifest Destiny as a natural and necessary part of American expansion. The second source was an article about the backlash to the Gap T-shirt, highlighting the modern-day criticism of the idea.

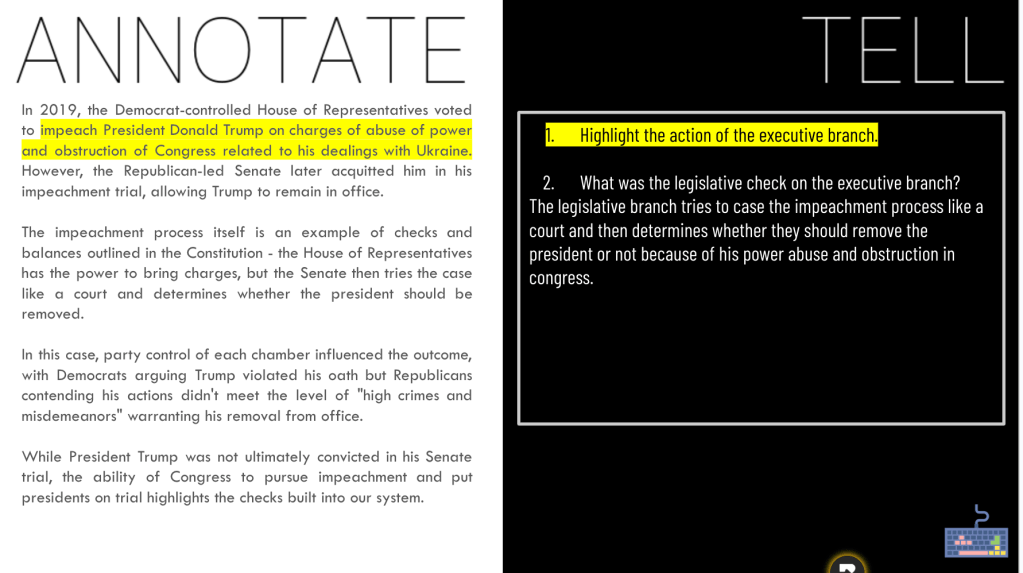

Students took notes on the key ideas from both sources, categorized them into three sections—historical context, positive perspectives, and negative perspectives—then wrote a main idea sentence. They combined all of this information into a paragraph response and submitted their writing in Class Companion. Since the Ohio state test includes a two-source reading and writing essay, this activity was designed to mirror that format and give students practice organizing their thoughts and using evidence.

Why This Worked

This lesson reinforced a lot of important skills beyond just memorizing historical facts. Students generated their own questions, analyzed visual sources, compared perspectives, and practiced structured writing. The writing in Class Companion showed improvement—students were getting better at organizing information, crafting arguments, and responding to feedback. The next step in the unit will focus on westward expansion’s impact on different groups, continuing to build historical analysis, writing, and connections to the present.

Friday

Gamifying POV Writing: WeWillWrite & ShortAnswer

We started Friday by wrapping up unfinished work from Thursday. Some students needed to complete their Class Companion writing on Manifest Destiny, while others who had finished moved on to labeling and coloring a map of westward expansion territories. Once that was taken care of, we shifted into a creative writing activity, using WeWillWrite and ShortAnswer to explore point of view (POV) writing in a gamified way.

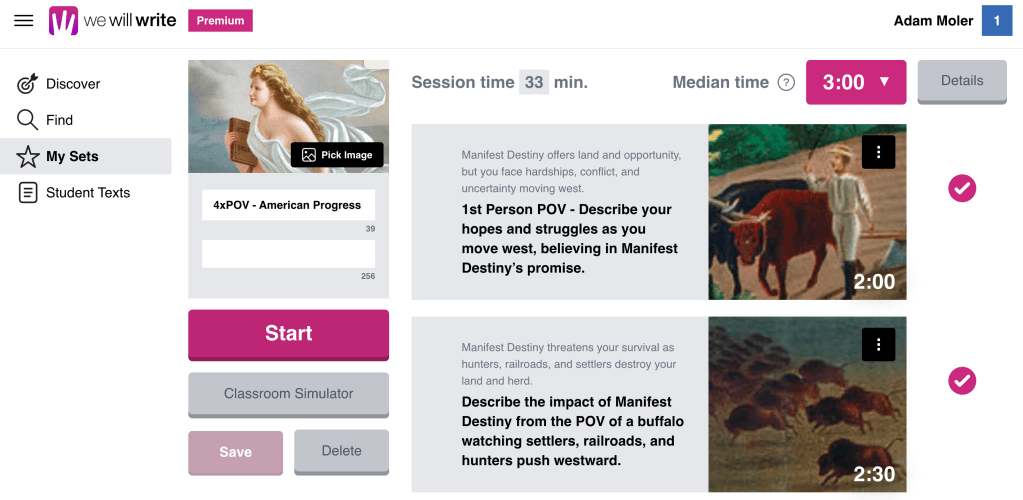

WeWillWrite: POV Writing with Columbia, Natives, Farmers, & Buffalo

For most classes, I used WeWillWrite, a platform that gamifies writing in a way that engages all students. Back in December, I used it for general writing practice, but now you can create custom sets—a feature I didn’t know about until Lucas George mentioned it. I jumped on the chance to create a POV set based on the painting American Progress by John Gast. Students wrote from the perspective of Columbia, Native Americans, Farmers, or the Buffalo, responding to a timed prompt.

Here’s how it worked:

✅ Students logged in with a random pseudonym (just like Gimkit).

✅ They were placed into teams and given three minutes to respond to the prompt.

✅ They could see hints and teammate responses to refine their writing.

✅ Each team voted on their strongest response.

✅ The top four responses battled it out for class-wide voting and points!

✅ We repeated the process for two more rounds, deepening their engagement with perspective writing.

The energy in the room was fantastic—students were thinking critically about how Manifest Destiny impacted different groups, but in a way that felt like a game.

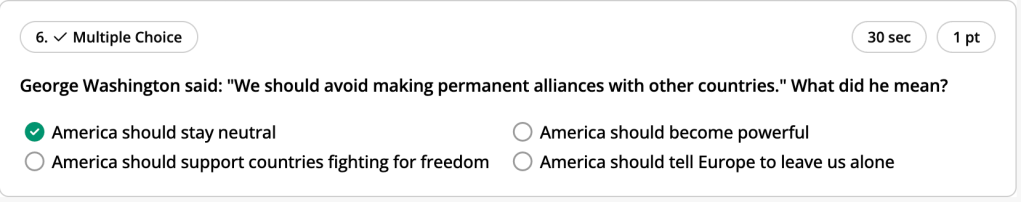

ShortAnswer: Live POV Battle Royale

For 6th period, I decided to switch things up and use ShortAnswer instead. This tool is similar to WeWillWrite but allowed me to create POV questions on the spot. One thing I loved was the built-in voice typing feature, which helped several of my students, especially those with IEPs.

Here’s how the ShortAnswer Battle Royale worked:

✅ I set up a POV question (e.g., “How would a Native American describe Manifest Destiny?”).

✅ Students had five minutes to respond.

✅ After the timer ended, I hid student names (lesson learned—forgot at first, and it became a popularity contest).

✅ Responses were randomly grouped into quadrants, and students voted on the best one.

✅ The top four moved on to a semifinal vote.

✅ The final two battled it out for the top spot.

The hidden names made a huge difference. Suddenly, students who rarely get recognized for their writing were winning! One student on an IEP finished in the top three twice, and after his second win, he threw his arms up and said, “I never win anything!” Absolute highlight of the day.

I also liked how AI-generated sentence stems and outlines helped guide students in their POV writing. Students who typically struggle to write were producing full paragraphs and competing to win. The ability to attach readings and pictures to questions made it even stronger.