Being at a new school means I’m living inside a learning curve. One is the learning curve of new procedures, figuring out how things run in a building that isn’t second nature to me yet. The other is learning about my students, how they learn, what they know, and what still feels brand new.

Technology has been the most eye-opening part. I’ve had to scale back some of my tech usage because I’ve noticed things I didn’t expect: students struggle when switching from tab to tab, they freeze when asked to transfer information from paper to a Chromebook slide, and some are still working hard at typing itself. Even something as simple as highlighting text in a slide became a full-class tutorial. But here’s the thing, they give everything they have. They want to be right, to be thorough, to do it well. So when a “simple” Map & Tell or Annotate & Tell takes longer than I planned, it isn’t because of disengagement, it’s because they are pouring themselves into it. That’s a learning curve I’ll gladly navigate.

Tuesday: Audience, Purpose, and Bias

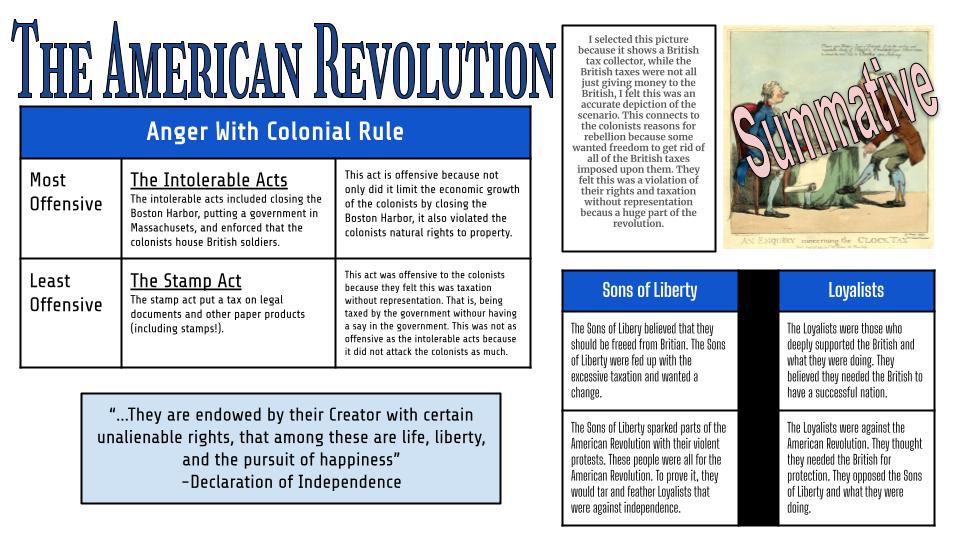

This week we continued our historical thinking skills with a focus on audience and purpose and how those shape bias. I kicked things off with Paul Revere’s famous engraving of the Boston Massacre. I just put it up on the screen and asked, “What do you notice?” Students jumped in with their observations, and then I followed with a question that caught them off guard: “Since this was known as the Boston Massacre, how many people do you think died?”

The guesses rolled in, 15, 213, 500, 30. When I told them the real number was 5, their jaws dropped. Suddenly, the engraving looked different. That one moment opened the door for a deeper conversation about perspective and purpose.

Annotate & Tell

From there, we moved into an Annotate & Tell activity using two primary source newspaper accounts (thanks to the Gazette and the Chronicle). Students highlighted key words and answered guiding questions:

- Who is the intended audience for this source?

- What is the author’s purpose?

- How does the description work to support that purpose?

It was a challenge at first, some students even asked, “Where do I type my answer?” But once we got rolling, they dug into the language, spotting words and phrases that revealed bias and purpose. The more they looked, the more the accounts felt less like “the truth” and more like arguments meant to persuade.

Final Reflection

We wrapped with a reflection that asked students to think about which version was more convincing to its audience and to use evidence from the text to support their reasoning. Some sided with the Gazette, some with the Chronicle, but what mattered most was that they were weighing sources against each other, not just accepting them at face value…….

This week reminded me that learning curves aren’t setbacks, they’re signposts. They show me where my students are, what tools they need, and how much they care about getting it right. If that means slowing down a bit on tech or taking extra time to show how to highlight, then so be it. The payoff is worth it, students not only practicing historical thinking, but also realizing that history isn’t about memorizing, it’s about perspective, audience, and purpose. Room 103 is learning. And so am I.

Wednesday: Resource Rumble Review

Midweek was all about review. To get ready for the test, I set up a Resource Rumble. Around the room I had seven envelopes, each tied to a different historical thinking skill. One had primary sources, another secondary, another sourcing, another contextualizing, and so on. Students worked in groups, pulling tasks from each envelope and building their study guide as they went.

Once they thought they had an answer, they brought it to me for approval and feedback. If it was solid, they got to roll dice and collect that many Jenga blocks. The twist was that their blocks weren’t just points, they had to build the tallest freestanding tower by the end. The room buzzed with movement, laughter, and some serious strategy as groups tried to balance accuracy with architecture. They loved it. I think part of the appeal was that it felt new, they got out of their seats, and for once it didn’t involve technology. By the end, they were smiling, competing, and most importantly, ready for Thursday’s test.

Thursday: Putting Skills to the Test

The test itself was designed to be straightforward but intentional. I built it in three parts: multiple choice, think alouds, and performance tasks that practiced the skills we had been building. The multiple choice section mixed DOK 1 and DOK 2 questions focused on primary and secondary sources, sourcing, contextualizing, corroborating, close reading, audience, purpose, and bias.

The think alouds were something different. Students read quotes like, “John Smith wrote about himself saving Jamestown. But I’m stopping to wonder… was he bragging to make himself look good? Which skill am I using when I question his reason for writing?” These items pushed students to recognize the historical thinking skills in action, not just definitions on a page.

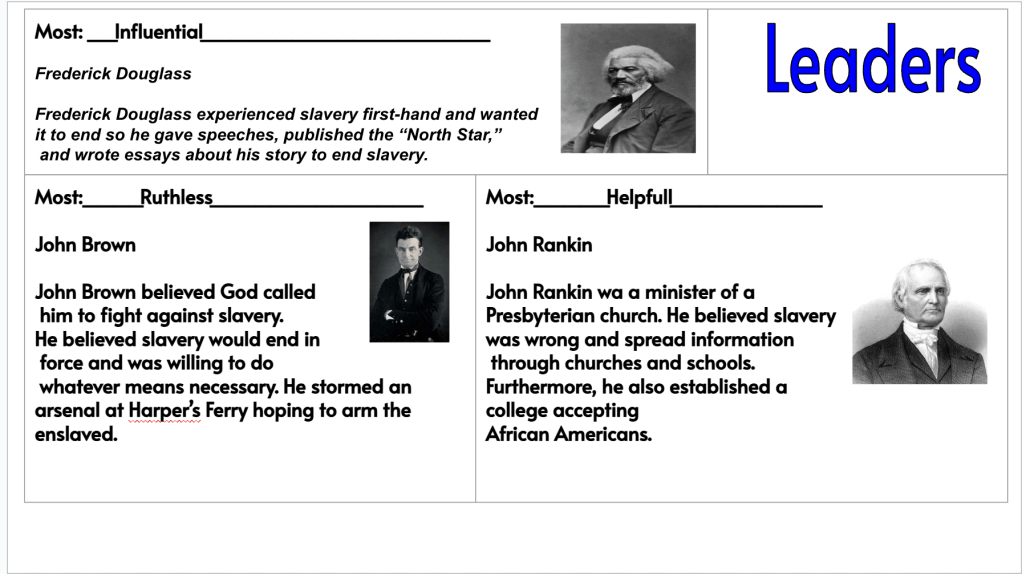

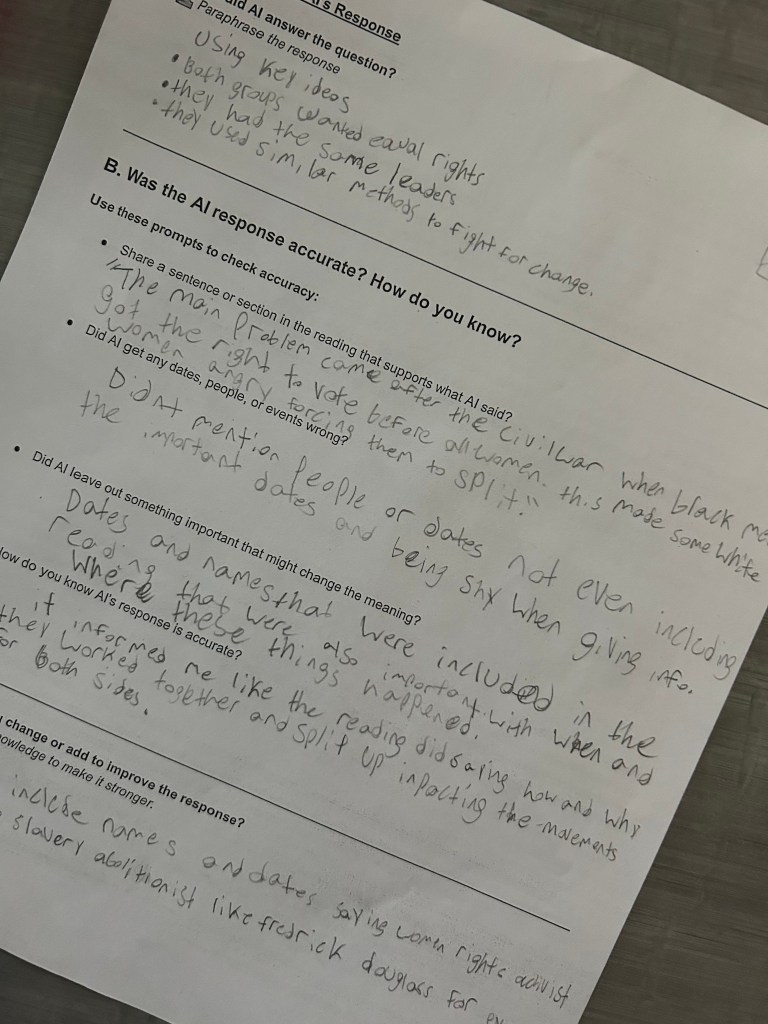

For the performance tasks, I wanted them to work with sources, write, and apply what they knew. They sourced and questioned the reliability of the Boston Massacre engraving, contextualized a painting of Plymouth Rock, and compared sources on John Brown to analyze audience, purpose, and bias. I leaned on ChatGPT to help me design the framework, then revised and added the touches I knew my students needed. It ended up being a clean, balanced test that gave me a true look at how they’re progressing.

Friday: A Stumble into Number Mania

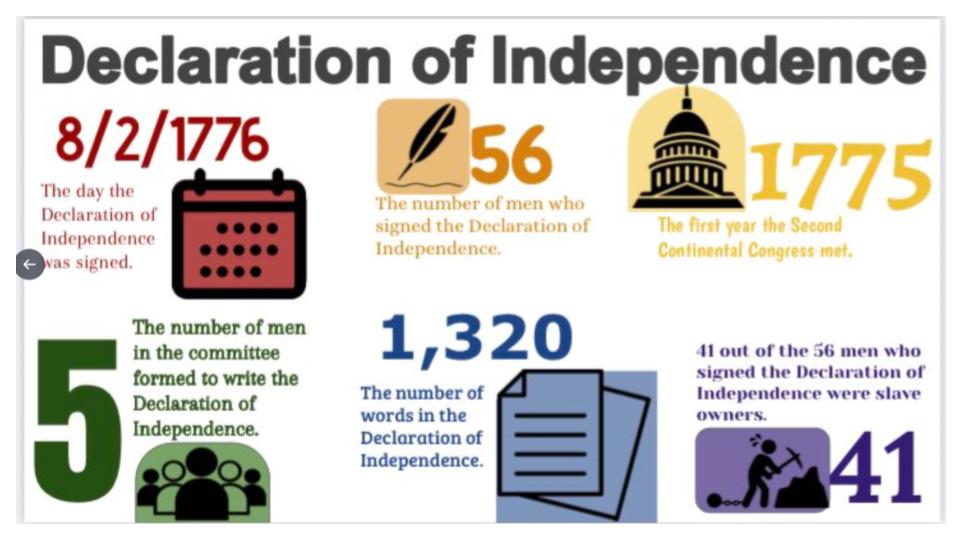

Friday I tried to roll out our new unit on Native Americans and European exploration and colonization with two Map & Tells and a Number Mania. The problem was we had never done a Number Mania before, and I ignored my own advice about starting small. What I got instead was a front row seat to how much my students still struggle with basic Chromebook and Google Slides skills. Adding pictures, changing word art, duplicating shapes—things I thought were second nature—turned into major roadblocks. At one point I was even being asked what the title should be. Good grief.

It was frustrating for them, so I pivoted. For my next three classes, I had them create a Number Mania about themselves, picking four numbers that told a story about who they are. I walked them through step by step: how to insert and format pictures, what word art is, how to change it, and even the magic of Control+D to duplicate. It wasn’t what I originally planned, but it gave me a better picture of their tech readiness and let them practice in a low-stakes, personal way.