This week, I took a hard look at my teaching approach and realized I had been falling into a pattern of overloading my lessons with too much traditional content. After reflecting and talking with Jon Corippo, I refocused my energy on using student-centered protocols that would both engage my 8th graders and keep the content academically rich yet accessible. We used a variety of strategies—starting with Fast and Curious to boost content retention, Graffiti Walls for movement and exploration, and Thick Slides for quick, meaningful summaries. By Friday, I brought everything together with a headline-driven lesson on Jamestown that sparked curiosity and used a mix of Google Maps, Wicked Hydra, and Wordwall. The result? A week that was fast-paced and engaging.

Monday

Coming into class on Monday, I was tired, and I knew I needed to pull out a creative, high-engagement lesson to get both myself and my students through the day. I decided to lean into interactive strategies that would keep everyone on their toes.

Starting with Gimkit: Fast and Curious

I started the day with a Fast and Curious session on Gimkit, which is an effective way to review material and build momentum. If you’re not familiar, Fast and Curious is a quick, repeated review activity that leverages competition. I uploaded questions about Spanish explorers that we had already covered, making it a review while subtly gauging where students stood on key facts and concepts. The class average ranged from 65% to 77%, but the real value wasn’t just in the scores—it was the immediate feedback and the students’ drive to improve. For anyone trying to build retrieval practice into lessons, Gimkit makes it fun and competitive, and you can track student progress instantly.

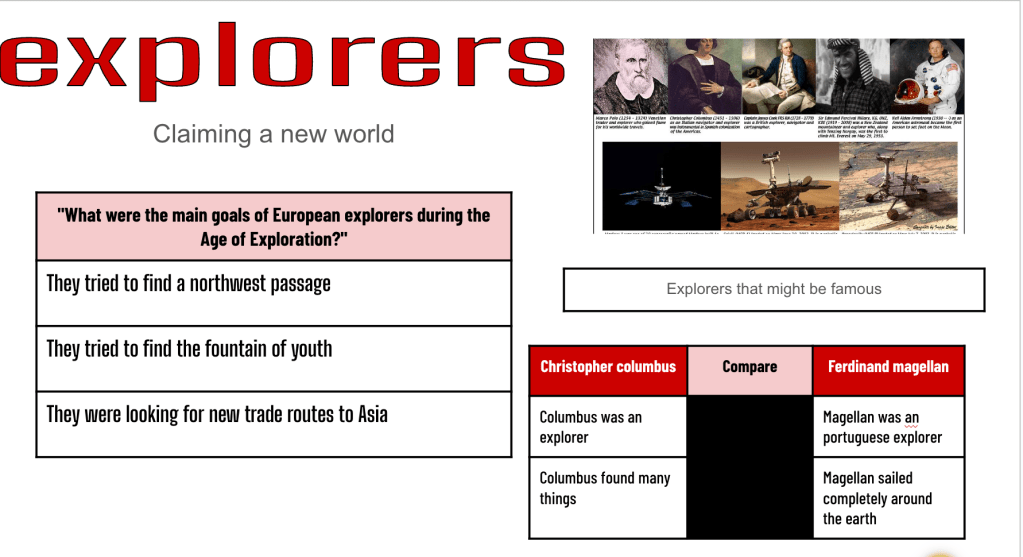

Explorer Scavenger Hunt: Moving Around the Room

Next, I had the students participate in an explorer scavenger hunt. This wasn’t just a passive worksheet activity—students were up, moving around the room, searching for answers about different explorers posted at stations. I tweaked the scavenger hunt by dividing the questions into Part A and Part B. I assigned each student to an explorer marked with either an A or B next to their name. This meant that students weren’t overwhelmed with all the questions at once; they could focus on smaller chunks of information, which worked well for those needing more structured guidance.

For setup, I stapled the explorer profiles and questions together and posted them around the room. Each station had information about a different explorer, like Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, and more. This tactile, physical movement not only keeps students engaged, but it also serves as a way to differentiate the activity. I find that students who struggle with longer reading passages or sitting still benefit from the opportunity to physically move around while learning.

A Layered Learning Approach

This lesson wasn’t just a one-off on explorers. It was part review and part preview. Monday’s scavenger hunt focused primarily on explorers that we had already covered, like the Spanish explorers, but I also introduced a few new explorers they would be learning about in more depth in Tuesday’s lesson. This gave the students some curiosity and set the stage for the rest of the week’s lessons.

By layering content this way, I’m not just throwing new information at them; instead, students have a chance to review and master familiar material while also preparing their minds for what’s coming next. This approach helps scaffold learning and ensures students are more comfortable when we dive deeper into the new material later on.

Wrapping it Up with Thick Slides

We ended the lesson with a Thick Slide activity. For those unfamiliar, this is a powerful summarization tool that asks students to process their learning on one slide. Here’s what I had them do:

- Share three or four important facts they learned during the scavenger hunt.

- Compare two explorers they read about (e.g., Cabot vs. De Leon).

- Add a picture related to exploration.

This structure hits several skills at once: content recall, comparison and contrast, and creative expression through visuals. The slides serve as a formative assessment, letting me see what they’ve internalized. It’s a great visual tool for students too because they synthesize what they’ve learned into something concise but meaningful.

Tuesday

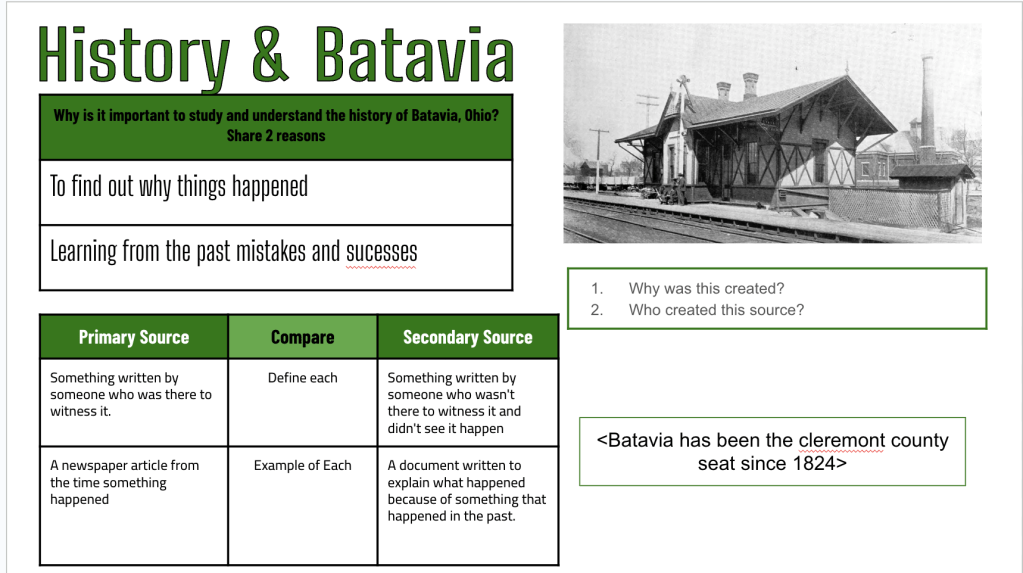

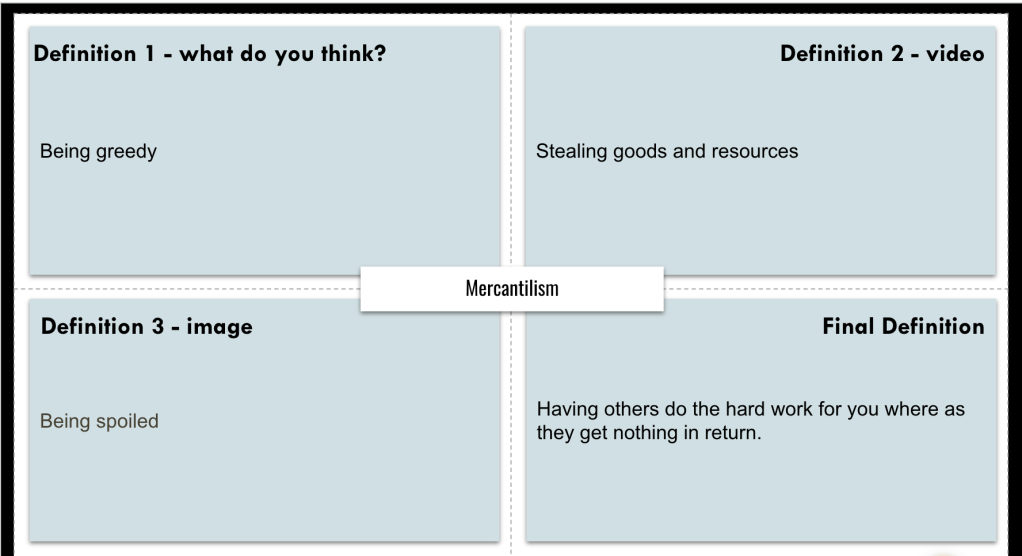

After a successful Monday, I kicked off Tuesday with a map activity that set the tone for another full day of exploration. The goal was to help students understand the colonies in the New World set up by Spain, Portugal, France, and the Netherlands, and how these countries played a role in shaping early America.

Map and Tell: Analyzing the New World Colonies

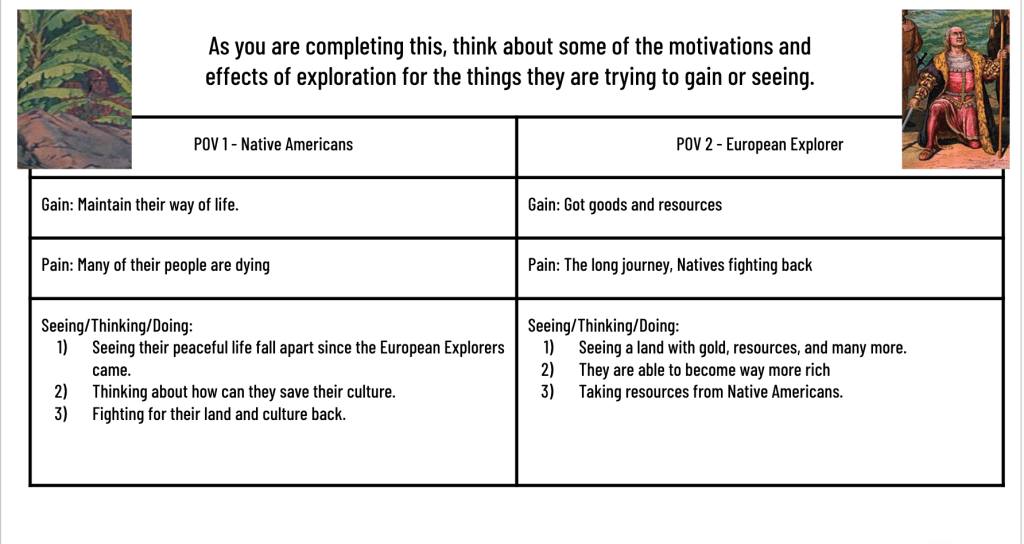

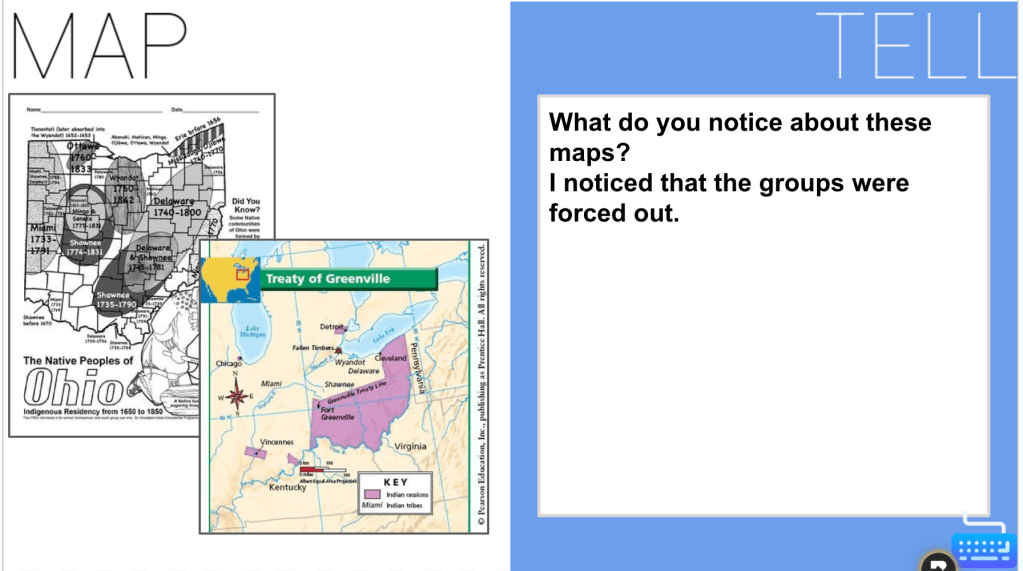

We began the lesson with a Map and Tell activity focused on the colonies created by Spain, Portugal, France, and the Netherlands. The students worked in pairs to analyze a map that outlined where these European powers had established their territories. Here are the questions they worked through:

- Which two European countries created colonies in the New World?

- What geographic trait did these colonies have in common?

- Why do you think European countries created colonies?

This analysis helped students build context and draw connections between geography and colonization strategies. The discussions around why these countries set up colonies set the stage for the next part of the lesson: Mercantilism.

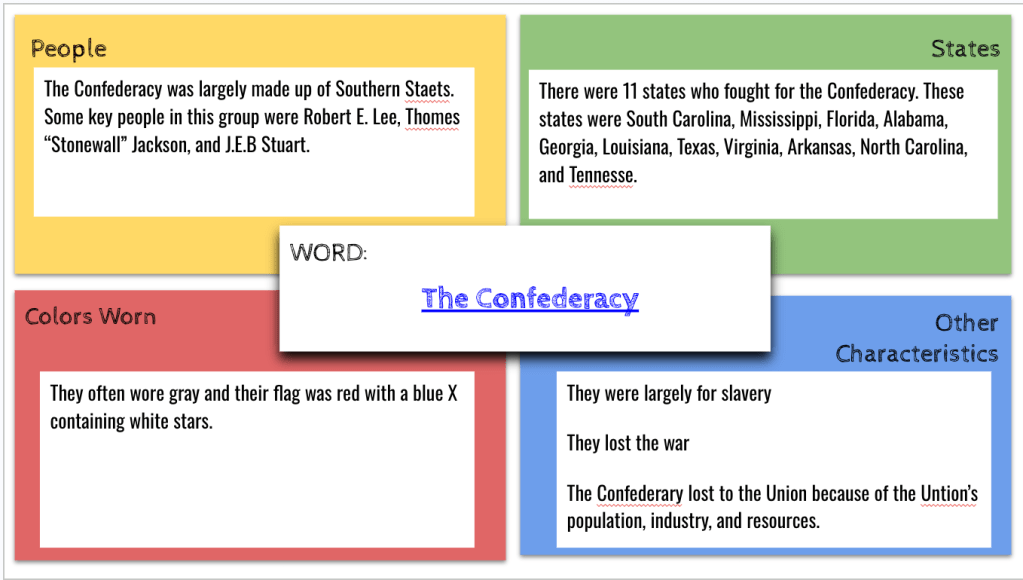

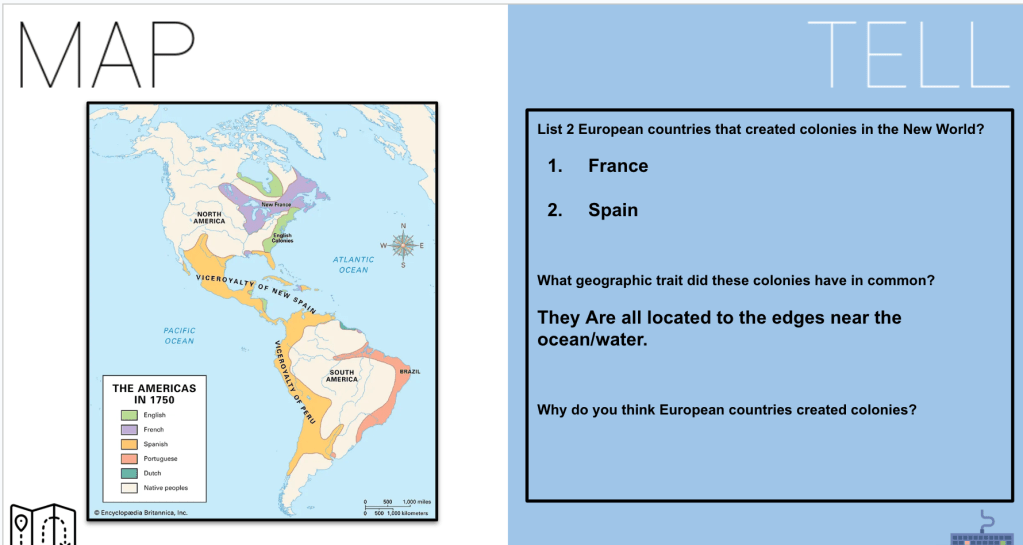

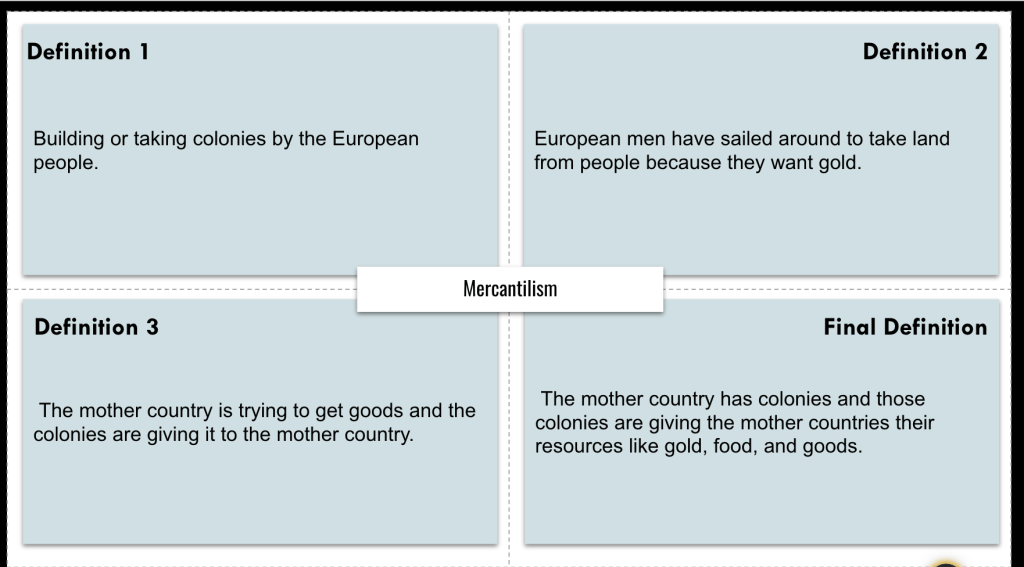

Frayer Model: Understanding Mercantilism

We then transitioned to a Frayer Model on Mercantilism, a concept that was new to most of my students. I asked them to first write down what they thought mercantilism meant—just their best guess. Once they were done, I had them angle their Chromebook screens.

Next, I showed a short video from Disney’s Pocahontas called “Mine, Mine, Mine.” It’s a 4-minute video that captures the essence of European greed and exploitation during colonization, which ties perfectly into mercantilism. After the video, I asked the students to revisit their definitions of mercantilism. Some students added new insights, while others completely redefined their initial thoughts, which was exactly what I was hoping for.

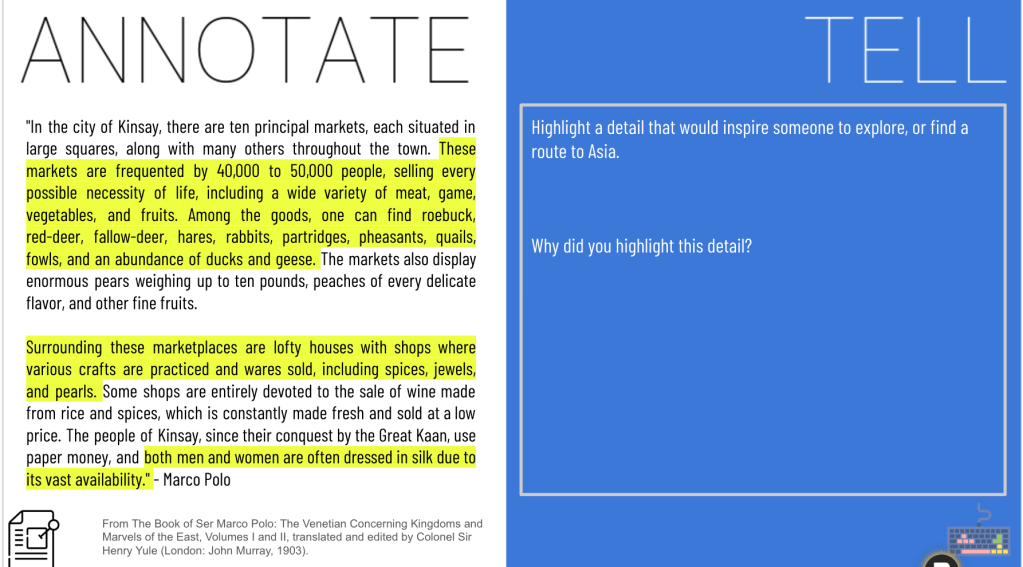

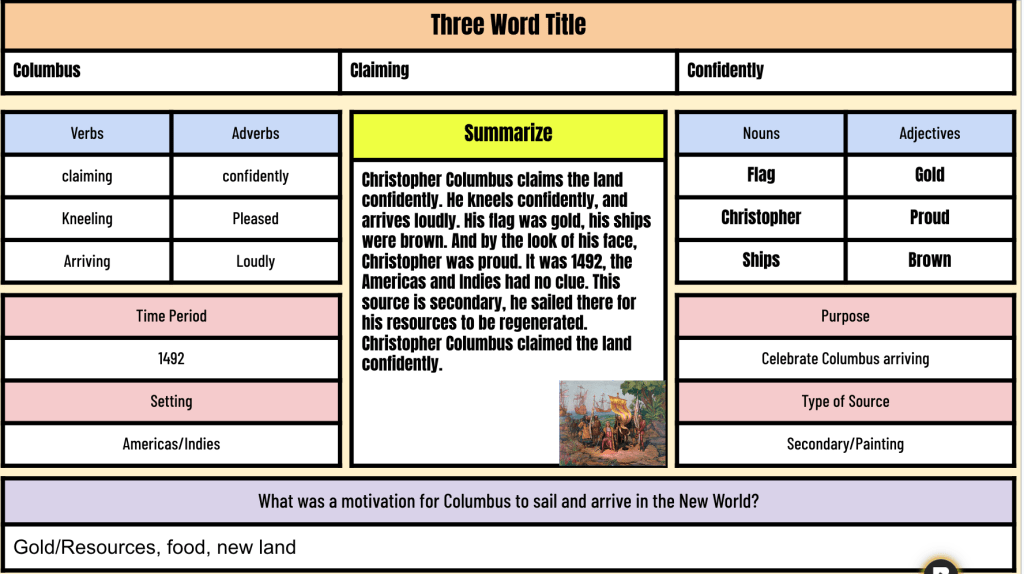

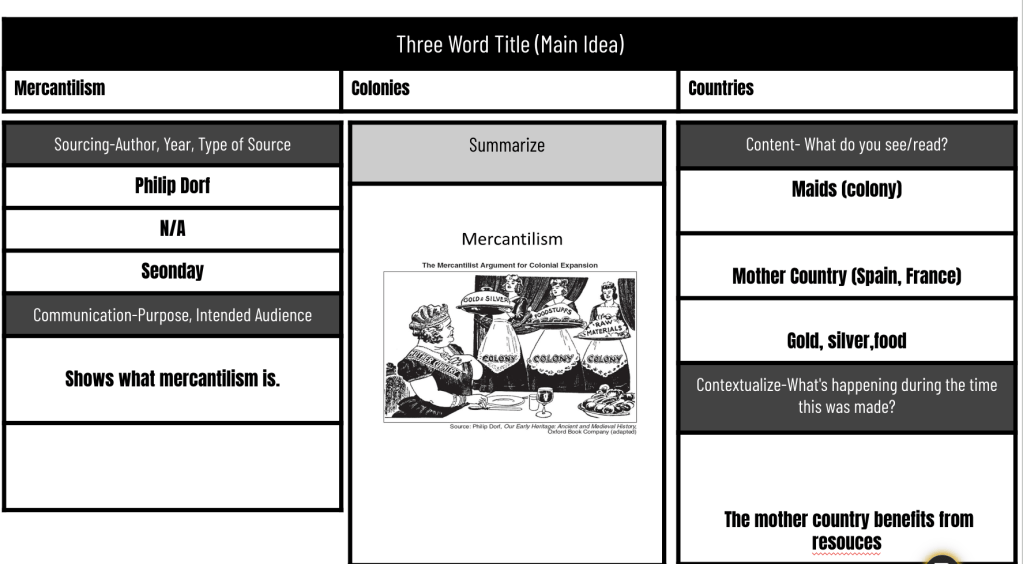

Sourcing Parts: Breaking Down Mercantilism Through a Cartoon

With a better understanding of mercantilism, we moved on to analyze the classic mercantilism cartoon. Using the Sourcing Parts EduProtocol, we broke the cartoon down by focusing on the following:

- Sourcing: Who created this cartoon? When and why was it made? What type of source is this?

- Summarize: What do you see or read in the cartoon?

- Contextualize: What was happening during the time this cartoon was created?

- Communicate: What is the purpose of this cartoon, and who was its intended audience?

The students dove deep into analyzing how the cartoon depicted European countries’ relentless pursuit of wealth through colonies and trade. It was great to see them apply their critical thinking skills to a visual source, reinforcing the concept of mercantilism and its connection to colonization.

Frayer Model Revisited

After the cartoon analysis, we returned to our Frayer Models to once again refine and add to our definitions of mercantilism. At this point, students had developed a far more comprehensive understanding, and their definitions were rich with historical context. The progression from initial guesses to a more nuanced definition was evident.

Socrative: Putting It All Together

To wrap it all up, I had the students share their final definitions of mercantilism on Socrative. This was a quick way for me to check for understanding and see who was still struggling with the concept. Overall, most students showed a strong grasp of how mercantilism shaped European colonization strategies in the New World.

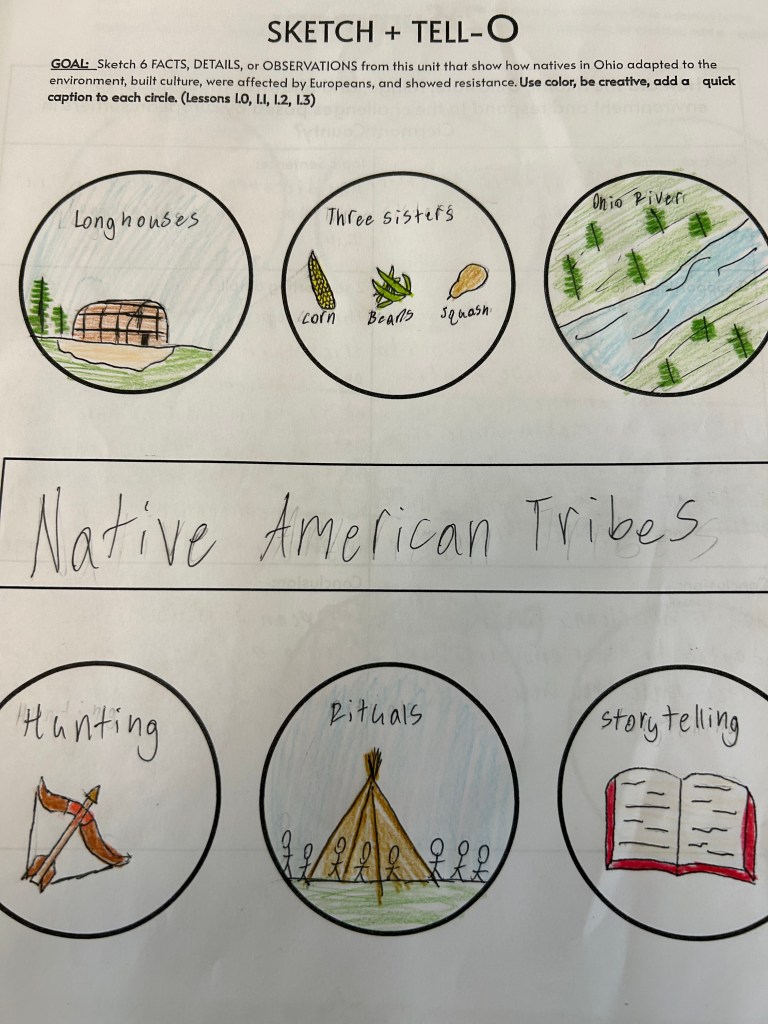

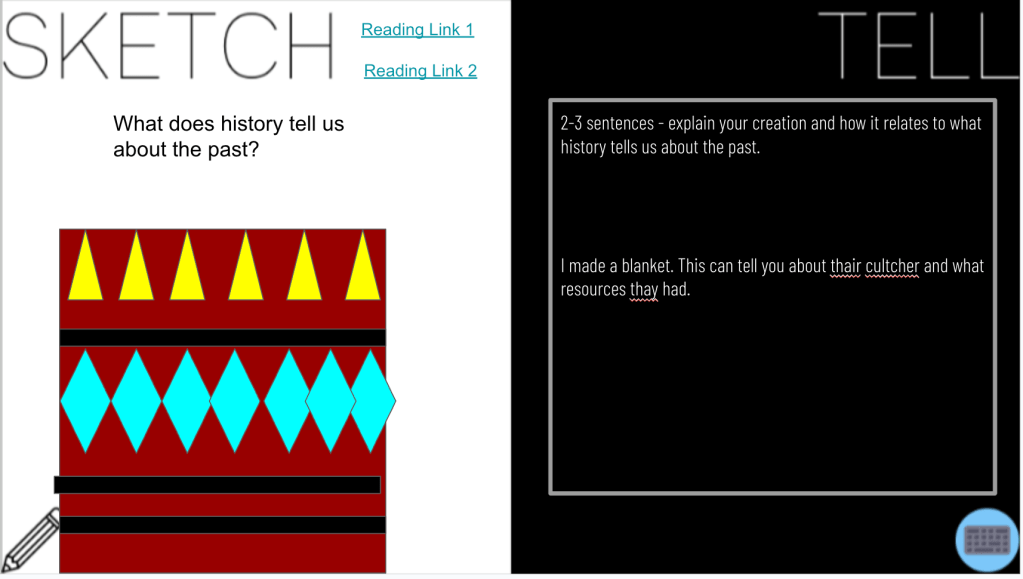

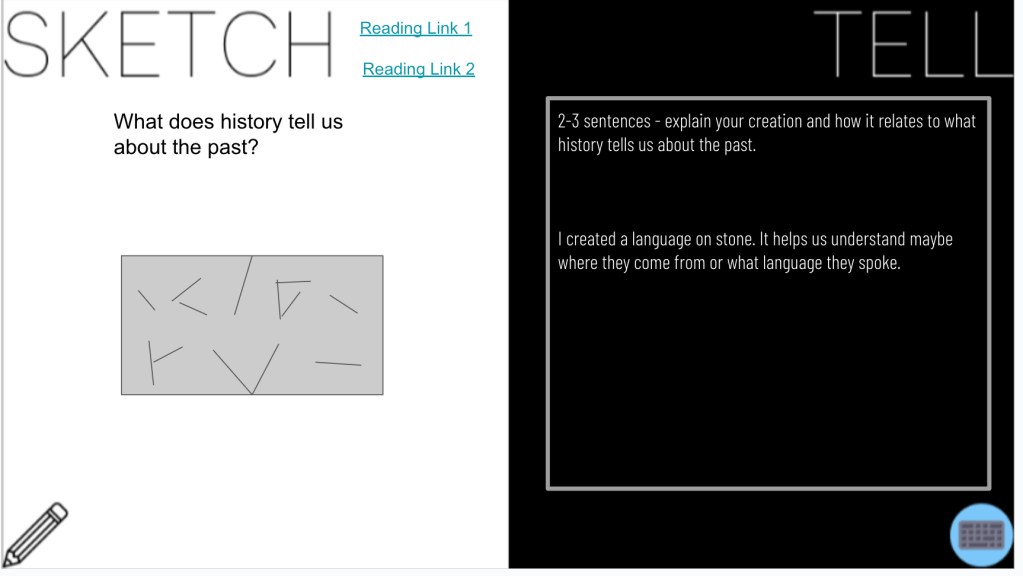

Sketch and Tell: Essential Questions

We finished the day with a Sketch and Tell activity. The students were tasked with answering the following essential questions:

- How does mercantilism relate to European colonization of the Americas?

- Why did the French explore and colonize the Americas?

- Why did the Dutch explore and colonize the Americas?

For each question, the students created a sketch to visually represent their answer and added a short caption. This activity gave them a creative outlet while reinforcing their learning. It also allowed me to gauge their understanding in a more visual and reflective way.

Looking back, I had originally planned to include a CER (Claim, Evidence, Reasoning) activity as the final part of the lesson, but I quickly realized it was a bit too ambitious for the time we had. The students were already processing a lot of new information, and adding a CER would have pushed us over the edge. Instead, we focused on sketching and summarizing, which worked out well for the time we had.

Wednesday

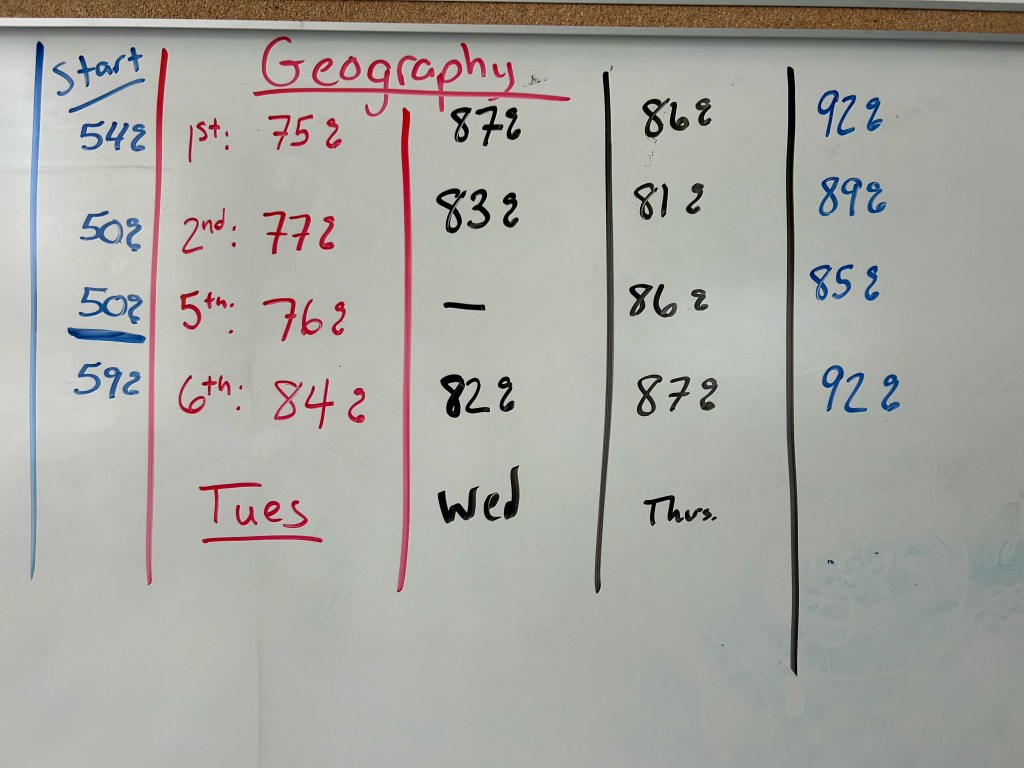

Wednesday was all about assessing what my students had learned throughout our unit on European exploration, but I wanted to ensure that they could see the purpose behind each activity we had done leading up to this point. The assessment was split into two parts: a Gimkit challenge and an annotated map, both designed to help students make connections between last week’s lessons and the material we had covered this week.

Part 1: Gimkit Challenge

We started the day with a Gimkit challenge, where I encouraged the students to push themselves to raise the class averages to 90% or higher. When we first began using this Gimkit last week, the class averages were sitting at 52%, 54%, 62%, and 58%. After practicing with it throughout the unit, the students were determined to hit the target.

By the end of Wednesday’s class, the final averages were 87%, 90%, 92%, and 89%. The improvement was incredible and showed how much they had retained through consistent practice and spaced repetition. More importantly, the students could see the direct results of their hard work, which motivated them to push even further.

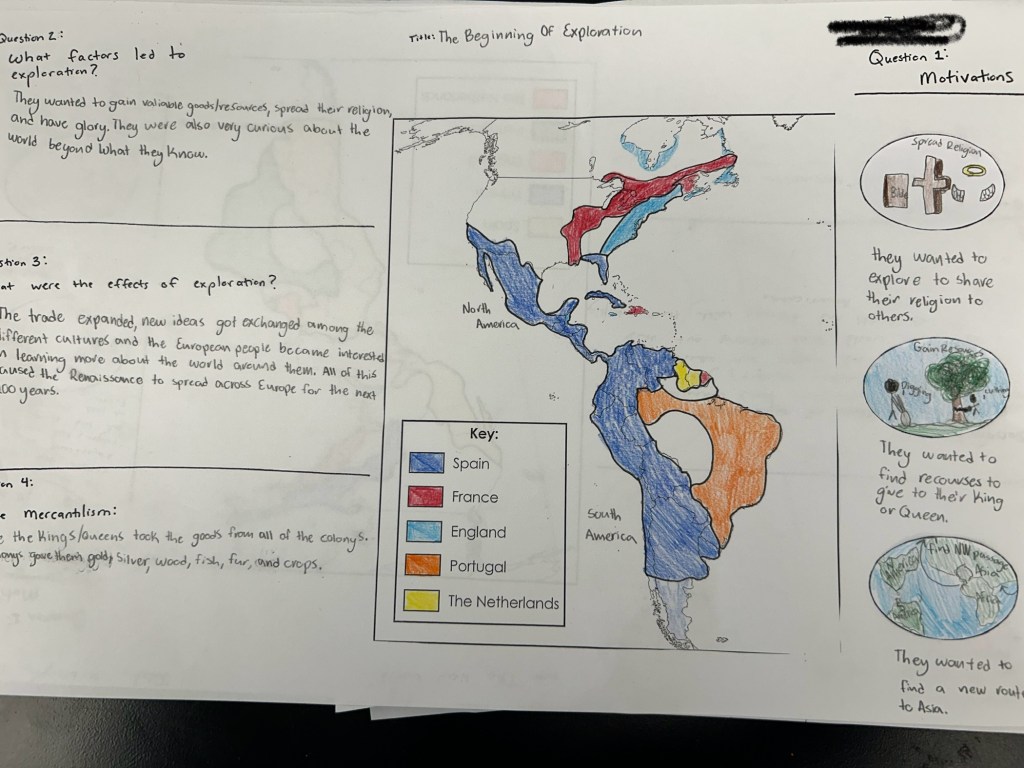

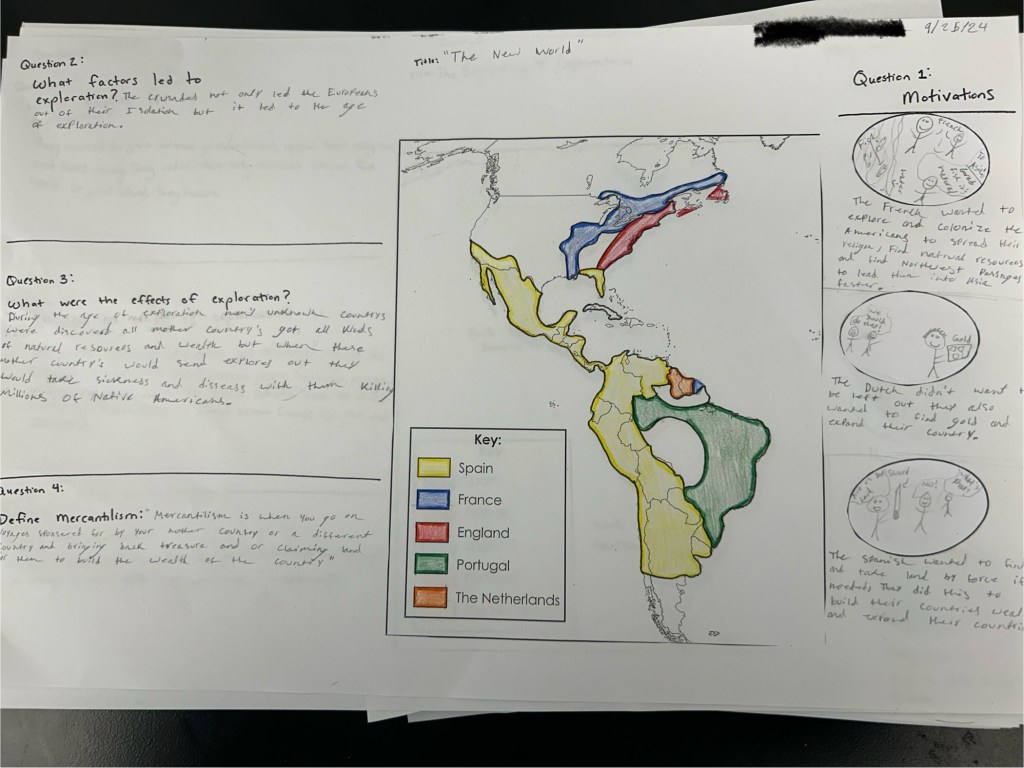

Part 2: Annotated Map Assessment

For the second part of the assessment, I had the students work on an annotated map that pulled together everything we had studied. Each student received a large 11×17 piece of paper with a blank map of North and South America in the center. The map required them to apply their knowledge of European exploration and colonization by completing a set of detailed tasks.

Here were the instructions they followed:

- Label and color the map for the territories claimed by different European countries using five different colors. They labeled both North America and South America.

- Add a title to the top of the map.

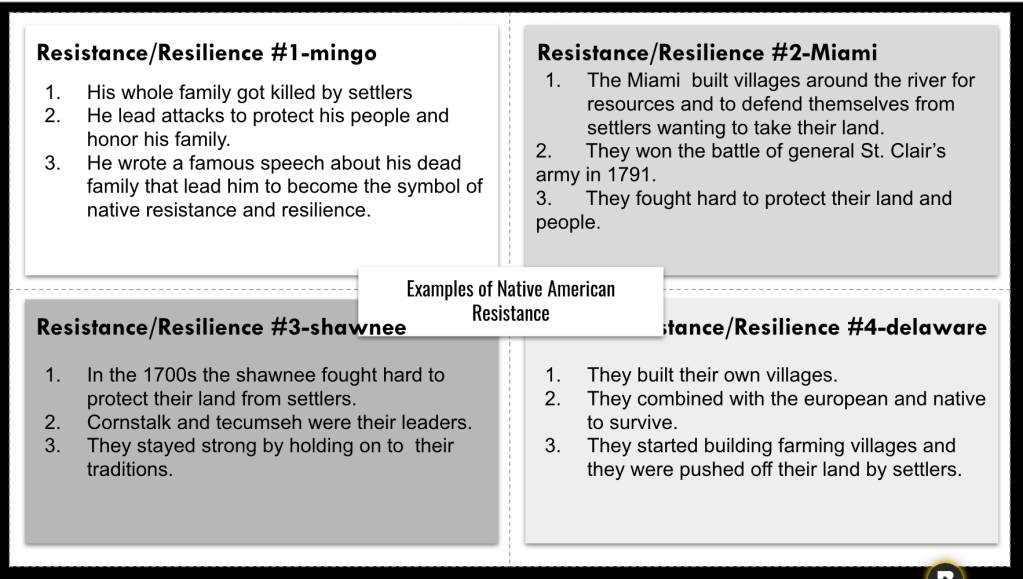

- Answer the following questions, referencing lessons from last week and this week:

- Question 1: What motivated Spain and France to explore and colonize the Americas? For this question, students cut out and glued three Sketch and Tell-o circles from Tuesday’s lesson. This connected the current task to earlier work, helping them see the purpose behind the activities we do.

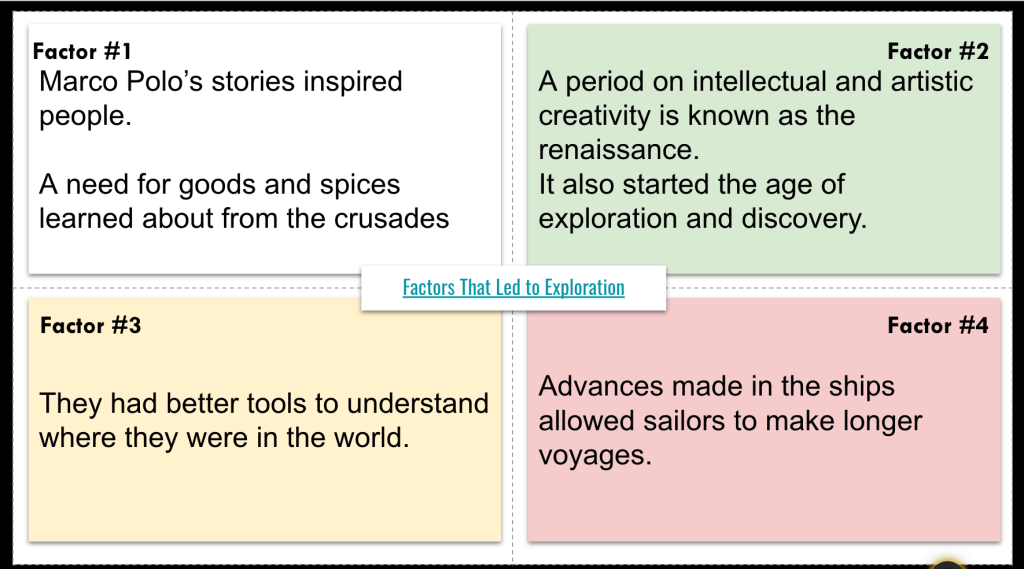

- Question 2: What factors led to exploration? They identified and listed two factors, referring back to lessons from the previous week.

- Question 3: What were the effects of exploration and colonization? They had to identify and describe three examples, using information gathered from multiple lessons.

- Question 4: Define mercantilism. This was a concept they had explored thoroughly on Tuesday, so they returned to their Frayer models to inform their responses.

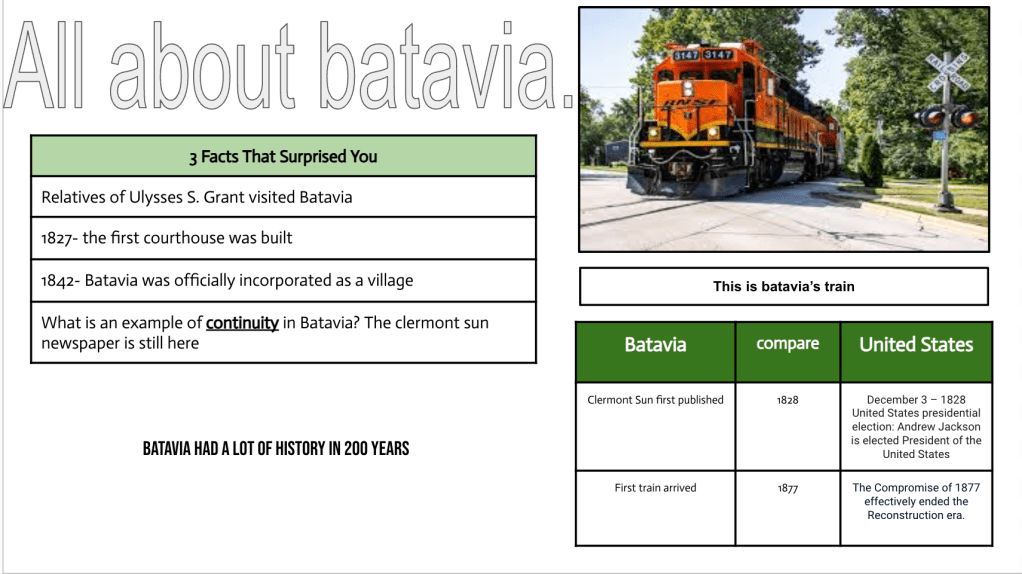

Using the Sketch and Tell-o circles from Tuesday was particularly important because it helped the students see continuity and purpose in the activities we’ve been doing. It wasn’t just a random task—it all tied together to help them form a bigger picture of the Age of Exploration.

The annotated map provided an opportunity for students to synthesize all of the information they had learned, while also allowing for creative expression. I was especially pleased with how the students used their previous lessons as a reference, connecting the dots between Spain and France’s motivations, the factors behind exploration, and the broader effects of colonization.

By having them revisit earlier lessons, they could clearly see the purpose behind the different activities we did throughout the unit. It helped them understand that each task—whether it was a Gimkit challenge, a Sketch and Tell-o, or a map activity—contributed to a deeper understanding of exploration and colonization. The process of going back to those lessons also gave them a sense of how much they’ve grown academically since the start of the unit.

Thursday

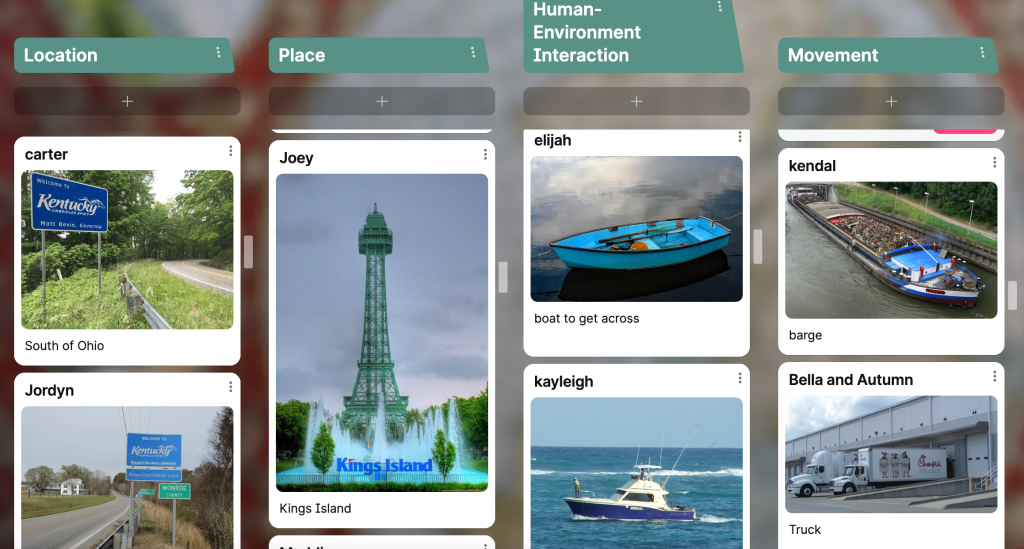

On Thursday, we dove into a brand-new unit on The English Colonies, and I knew I had to find a way to engage the students from the start. To get them moving and thinking about the topic, I started with a Graffiti Wall activity that had just the right mix of physical movement and competition.

Graffiti Wall: Gamifying Exploration of Textbooks

I placed textbooks on their desks, and right away, the students weren’t too excited. It’s a common reaction, but I was ready for it. I told them to look through pages 64-94 and find important words that could help them understand English colonization. Once they found a word, they had to raise their hand, and I called on them to come up to the whiteboard and write the word.

Here’s the catch: once a word was written on the board, it couldn’t be used again. This kept them on their toes, trying to find words that hadn’t already been claimed. The energy in the room picked up as they scrambled through the pages. And I had a “secret” word that added an extra layer of excitement. The secret word was Jamestown, and whoever wrote it down earned PBIS points. It was fun to watch as they eagerly searched for words that might give them an edge.

After about 10 minutes, the board was covered with key terms like charter, Plymouth, and middle colonies. I took a moment to give a brief summary of the upcoming unit, tying in all the words they had written on the board to help them see how these terms would fit into the bigger picture of English colonization.

The Great American Race: Teamwork and Discovery

Next, we shifted gears into a Great American Race activity, which was another chance for them to apply what they were starting to learn. I created 20 cards, each with a secret word like Jamestown, Plymouth, charter, or middle colonies. I handed out a card to each student, and their task was to create a Google Slide with four clues and one picture related to their word.

As they worked on their slides, I compiled them into a complete slide deck in order, giving feedback along the way. This allowed me to see how well they were connecting with the material and to guide them if they needed clarification on their clues or picture choices.

Once the slides were ready, I collected the cards and shared the completed slide deck with the class. The students then partnered up for the final part of the activity. Using their prior knowledge, the Graffiti Wall as a word bank, and some quick Googling, they worked together to figure out the answers to each slide. It was harder than they expected—many of the clues were tricky, and they had to really dig into their critical thinking skills to figure them out. But that was the point: this activity pushed them to apply what they had learned while collaborating and problem-solving.

It was a great day of active learning. The Graffiti Wall got them up and moving while building curiosity around the key terms for the unit. Gamifying it by making certain words off-limits and adding a secret word kept the energy high. The Great American Race followed that up by challenging their research and teamwork skills, while still keeping the fun element of discovery and competition.

The connection between the two activities—using the Graffiti Wall as a word bank for the race—reinforced the idea that everything we do in class has a purpose and that knowledge builds on itself. By the end of class, they had a strong foundation to start digging deeper into the history of the English colonies.

Friday

Friday was a day of reflection and adjustment for me. Being at a new school, I’ve been feeling like I’ve fallen into a bit of a rut—relying too much on traditional methods and dry content that just wasn’t resonating with my 8th graders. After talking with Jon Corippo, I realized I had been trying to do too much, often using material that lacked the punch needed to grab the attention of middle school students. I needed something quicker, more engaging, and with just enough academic rigor to feel worthwhile but still fun. And that’s when I came across an article that completely changed my approach to Jamestown.

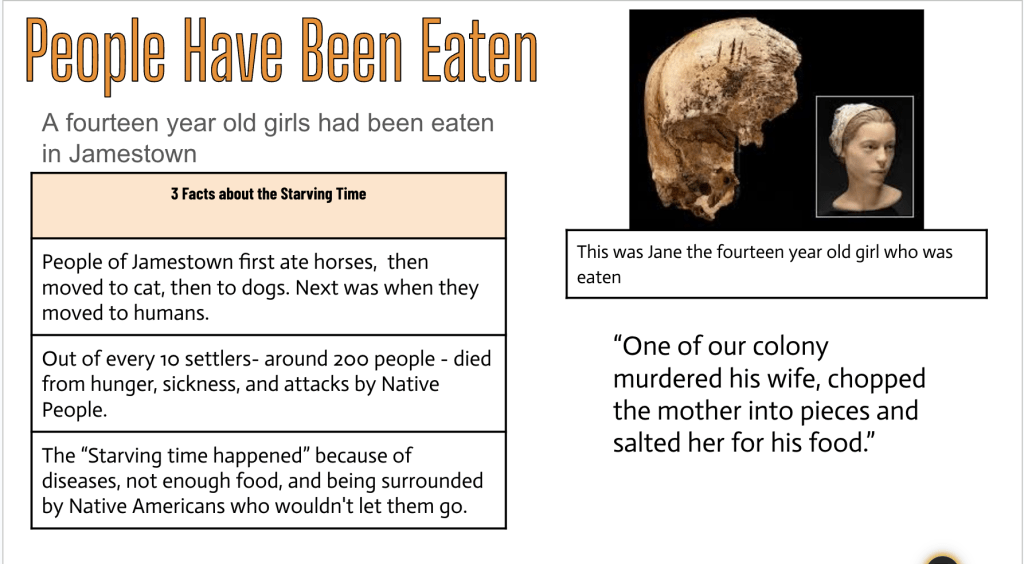

Hooking Them with a Shocking Headline

The headline I found was: “Jamestown Settlers Ate 14-Year-Old Girl.” I knew this would instantly grab their attention. When they walked into class, that headline was already on the board. I also had it printed on 11×17 paper at their desks, ready to go. You could feel the curiosity and the slight shock as they sat down and read it.

We began with a Wicked Hydra activity—an approach my students were already familiar with, where they had the chance to ask as many questions as they wanted about the headline. It sparked a lot of discussion right from the start, and students were eager to dive deeper. This was exactly the kind of engagement I had been missing.

Walking Through Jamestown with Google Maps

After the Wicked Hydra, we moved on to Google Maps. I had the students use Street View to explore the Jamestown site as if they were walking through it themselves. This added a layer of real-world connection to what they were reading, helping them visualize the setting where these historical events took place. They were completely absorbed in their virtual walk around Jamestown, and it set the tone for the rest of the lesson.

Exploring the Dark Side of Jamestown: Quick and Punchy Reading

Next, we dove into the one-page newspaper article that accompanied the headline. This reading was quick—just one page—but packed with bizarre details about Jamestown’s Starving Time and the unsettling choices the settlers had to make. The students were tasked with highlighting three weird facts and one crazy quote from the article. The headline had already captured their attention, and now they were digging into the details with enthusiasm.

Thick Slide: Summarizing the Starving Time

After reading, we shifted gears to a Thick Slide activity. In just 10 minutes, students had to create a summary slide that included:

- Three important facts about the Starving Time

- One surprising quote

- A relevant image

This quick-paced summary helped them process what they had just learned while keeping the focus on critical information. The format gave them enough structure to succeed while leaving room for creativity in how they presented their findings.

Wrapping Up with Wordwall and Gimkit

To finish off the class, we switched to Wordwall, where students did a drag-and-drop activity with the 13 colonies. I timed this for 8 minutes, and the students raced against the clock to correctly place the colonies in their respective spots. It was a fun, fast-paced way to reinforce geography while still keeping the focus on the day’s theme of colonization.

If we had any time left, we reviewed vocabulary on Gimkit to round out the lesson. This gave students one last chance to test their knowledge in a competitive, interactive format, keeping the energy high right up until the end of class.

Friday’s lesson was a turning point for me. The shocking headline, quick reading, virtual exploration, and fast-paced activities all combined to create a lesson that felt engaging and easy to complete while still being academically rigorous. The Jamestown article worked wonders in sparking interest, and using Google Maps and the Thick Slide brought the lesson full circle, helping students understand the reality of life in the early colonies. By simplifying my approach and focusing on keeping things interactive and relevant, I finally felt like I was hitting the mark with my 8th graders.