Monday and Tuesday

Monday and Tuesday were all about performance-based assessments. I’ve been wrestling with a question that probably crosses a lot of teachers’ minds at some point: Am I doing enough to prepare my students for what comes next?

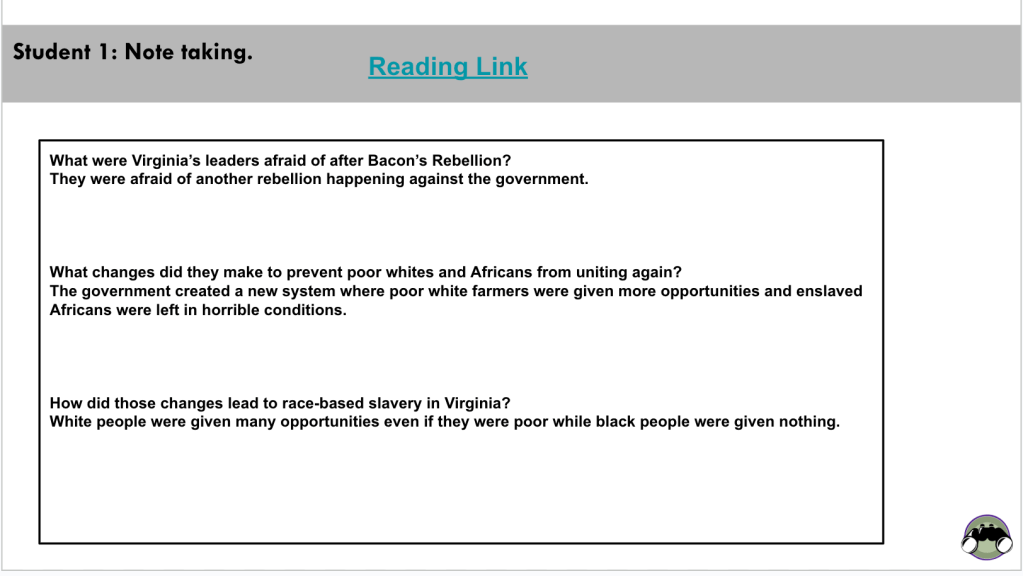

Most social studies classes lean on multiple-choice tests, short answers, and essays. I rarely do. My students spend more time creating, connecting, and explaining. Sometimes that makes me pause. Should I be giving more traditional tests? But then I look at the kind of learning that happens when students engage in performance-based assessments, and I remind myself why I lean this way.

Performance-based assessments ask students to show what they know. They mirror the kind of thinking and communication skills that matter beyond school: writing, presenting, and defending ideas. Districts that use capstones or portfolio defenses talk about how those assessments measure real understanding. I think the same is true in Room 103.

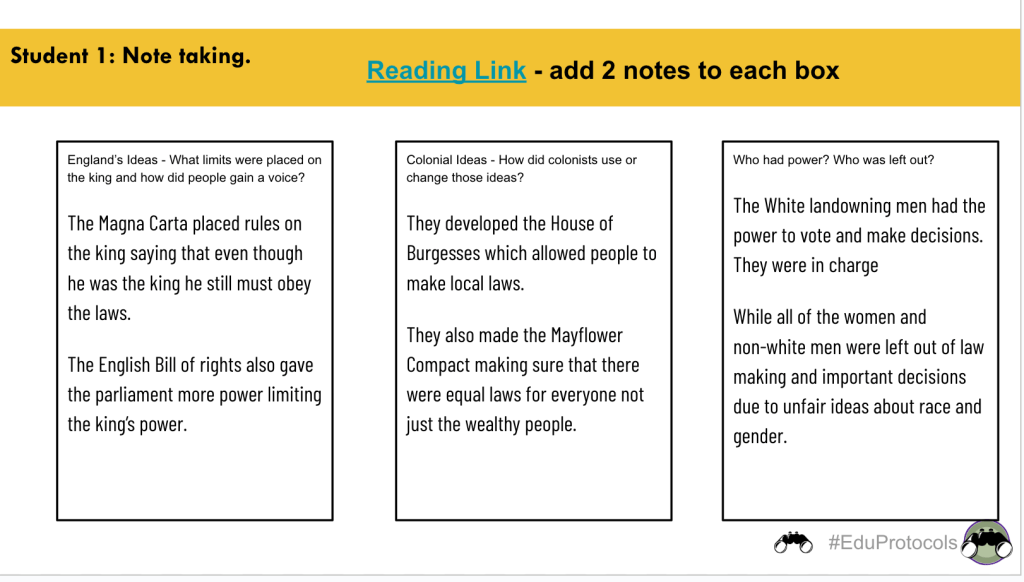

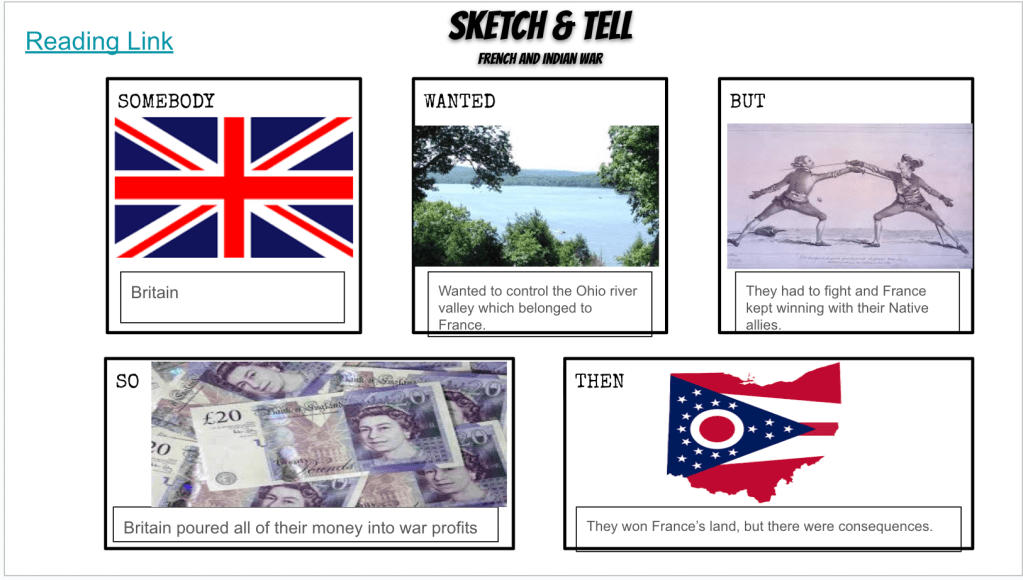

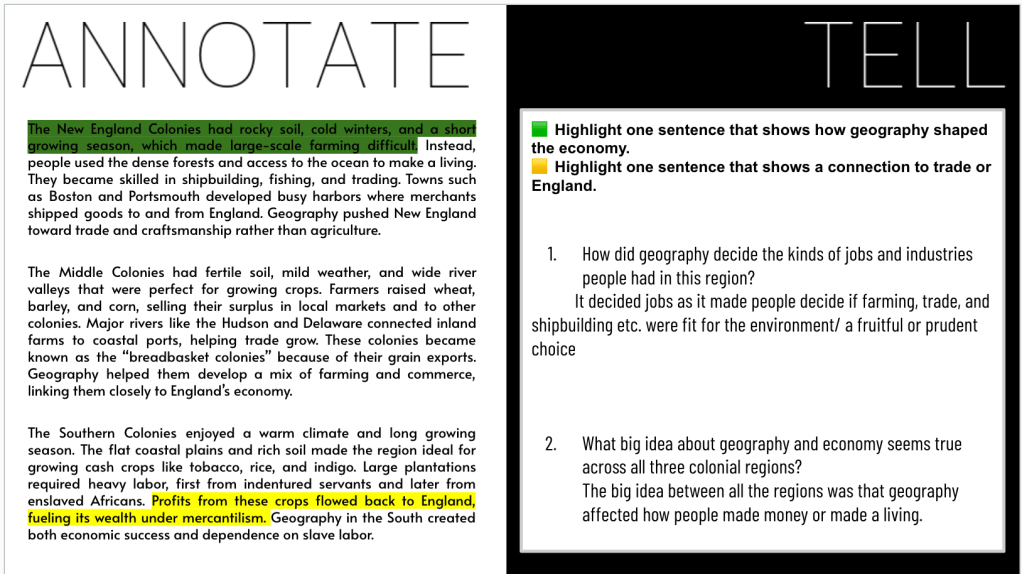

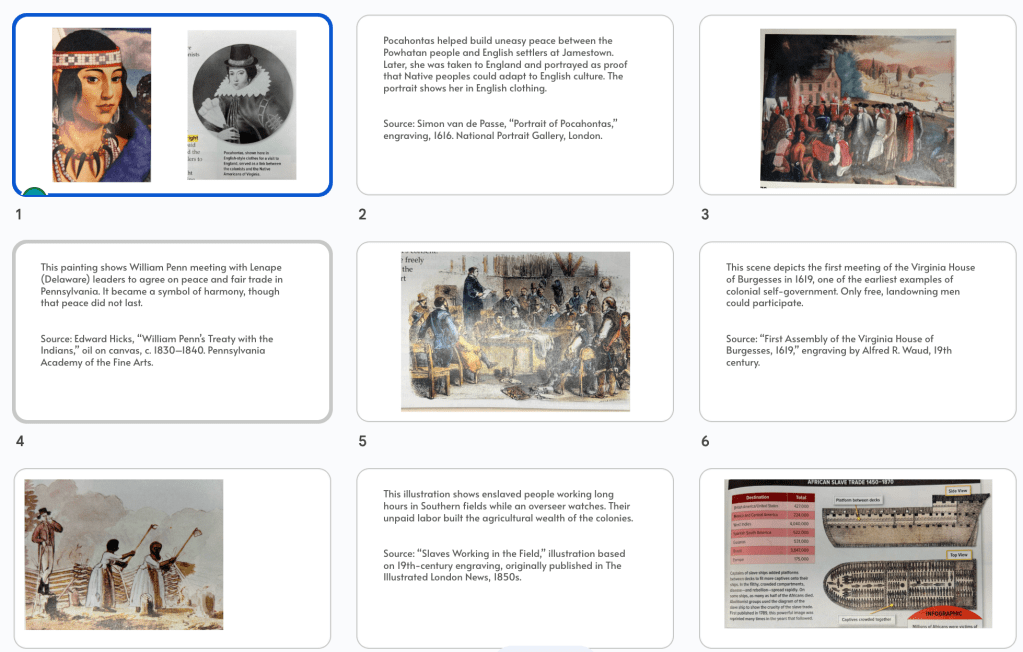

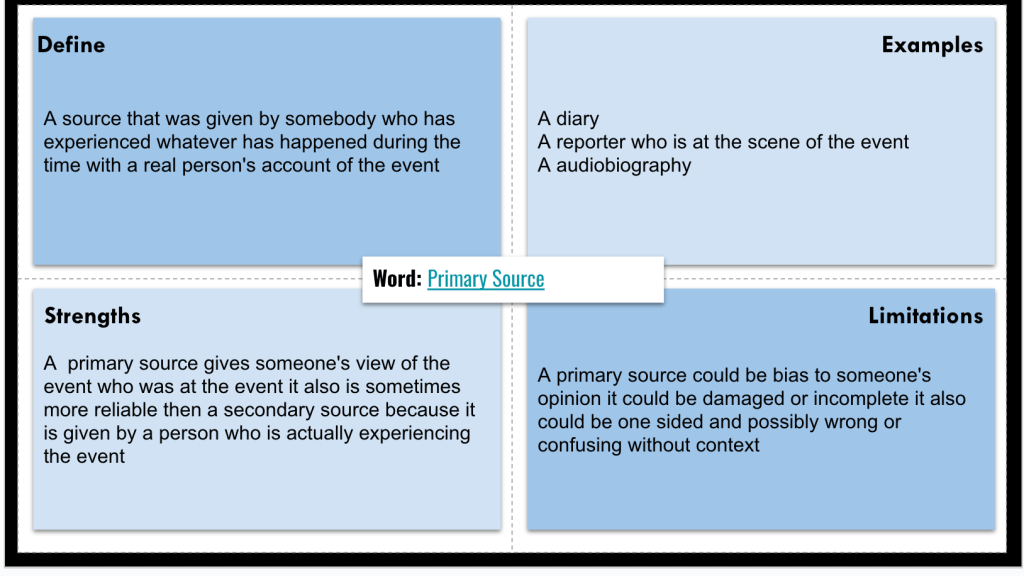

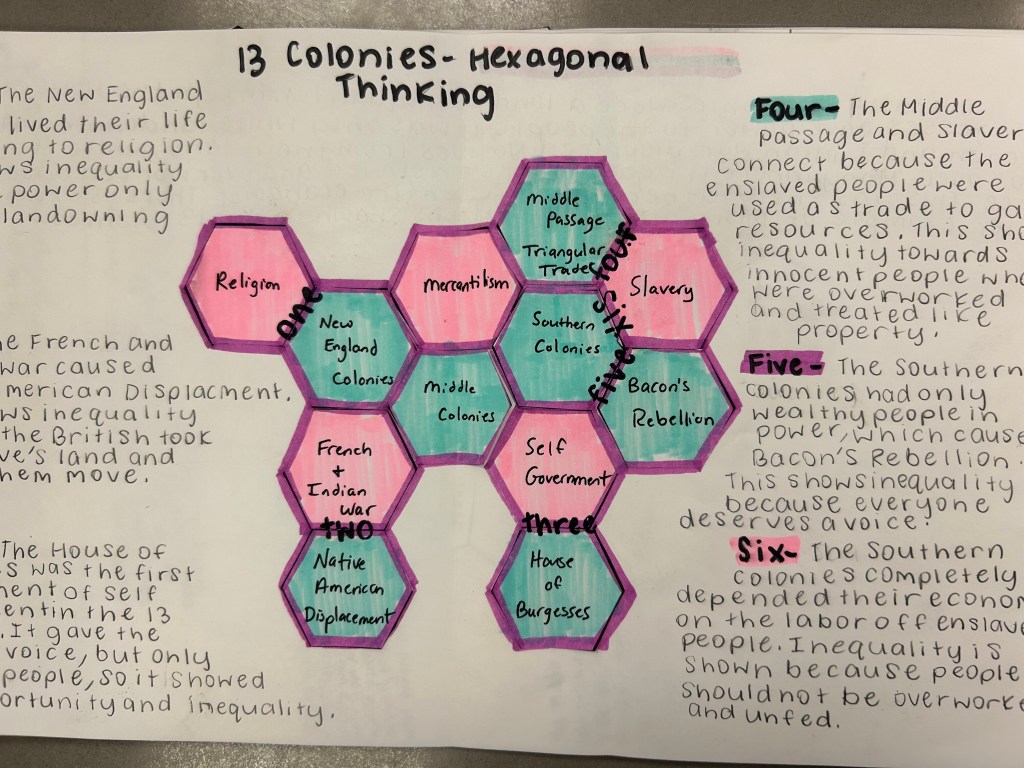

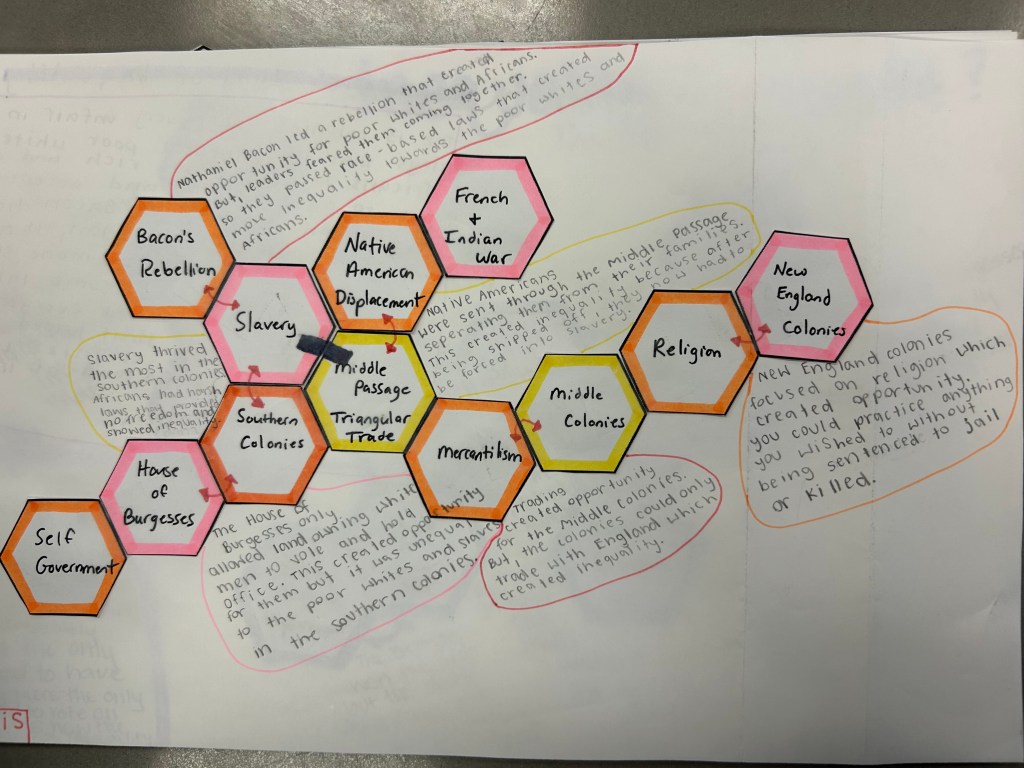

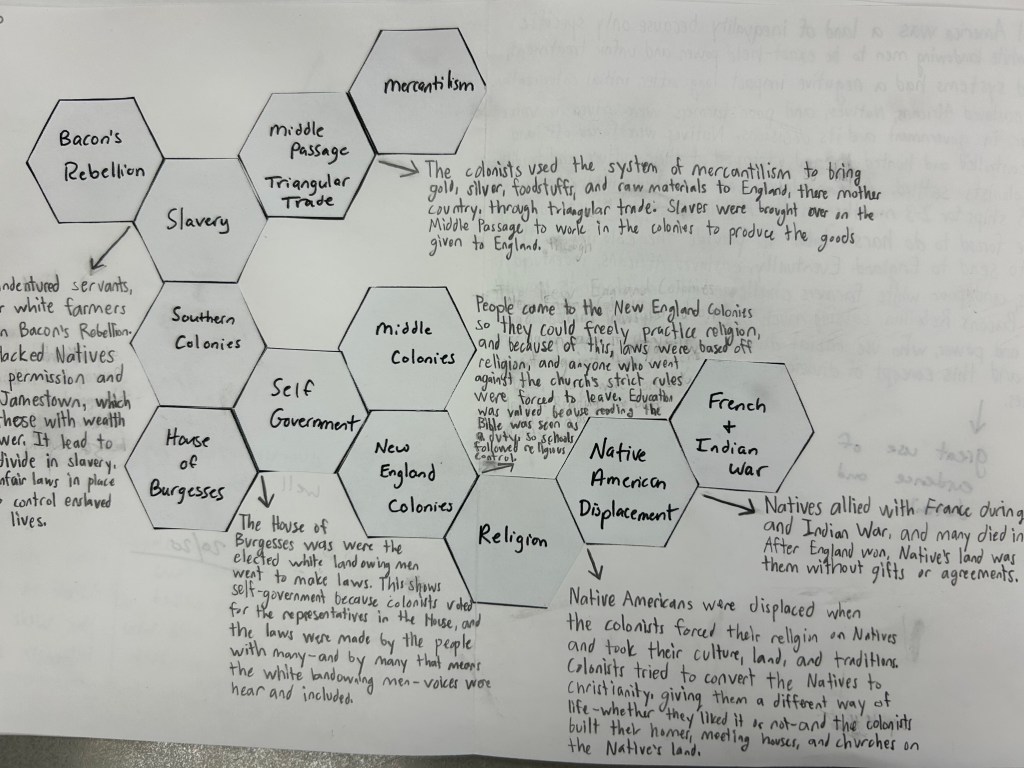

This week’s performance assessment was Hexagonal Thinking. Students worked with 12 hexagons representing key ideas from our 13 Colonies unit, including self-government, the French and Indian War, Native American displacement, slavery, and regional differences between the colonies. The task was simple in setup but deep in thinking. Students arranged the hexagons so that each connected to at least one other idea, then explained six of those connections.

Each connection had to relate to opportunity or inequality, tying back to our big question: Were the 13 Colonies a land of opportunity or a land of inequality?

The results were incredible. Some groups connected the French and Indian War to Native American displacement. Others saw links between self-government and inequality through voting rights. The conversations were thoughtful and honest. When students finished, they used their evidence from the hexagon connections to take a stance, opportunity or inequality, and defend it.

Two days, one performance assessment, and a lot of real thinking.

Wednesday: A New Road Begins

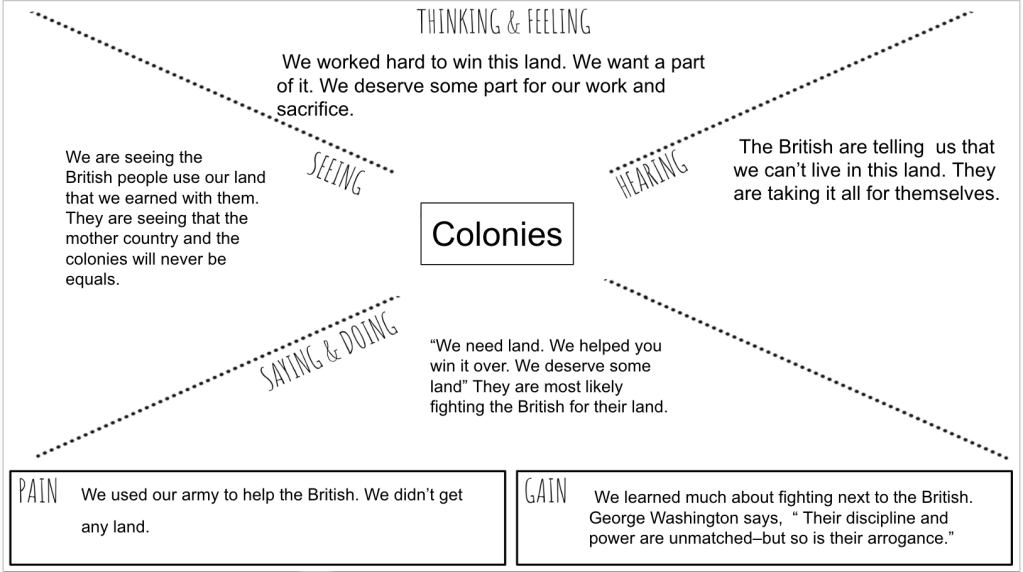

We kicked off a new unit on the Road to the American Revolution. Our new compelling question is: What caused British subjects to stop being loyal and begin fighting their own government?

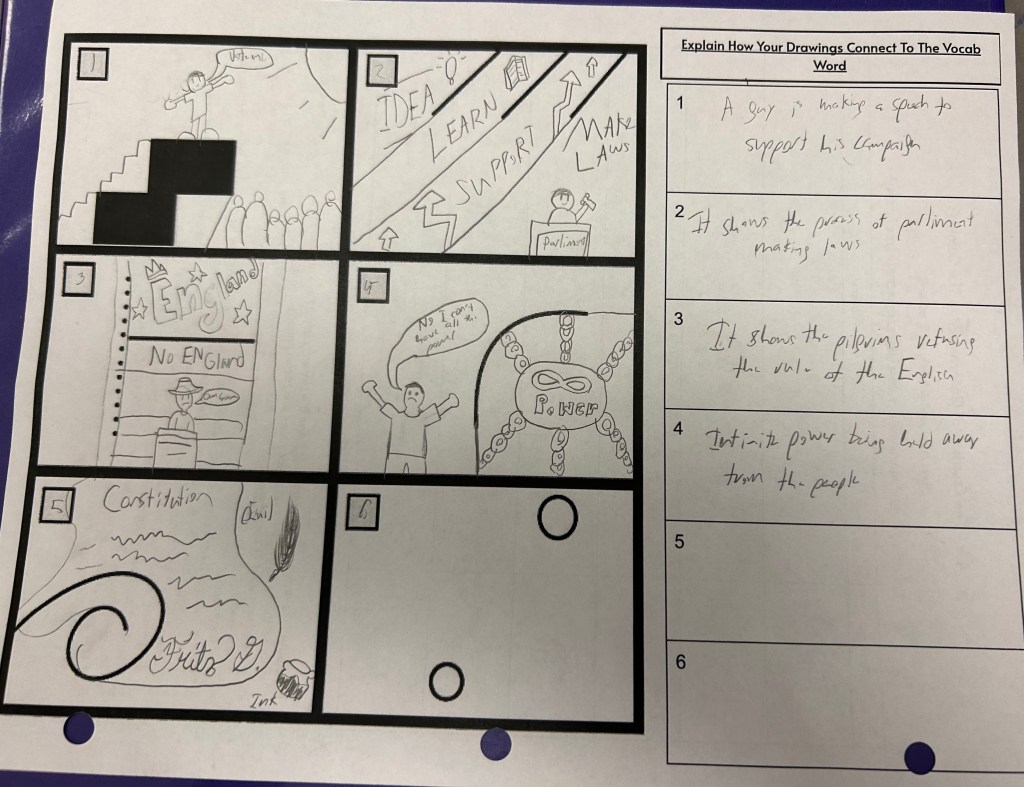

We started with a Blooket review of 17 vocabulary words. As students played, I handed out a TIP Chart (Term, Information, and Picture). After the round ended, students opened their Blooket results and chose 9 out of the 17 words they missed the most. Those were the ones they defined and illustrated.

This quick adjustment made the activity more purposeful. I’m also getting much better data from my Fast and Curious games now that I’ve been refining how AI creates my answer choices and distractors. The results are more reliable and more accurate, which makes the follow-up activities even stronger.

Our class periods were shortened to about 30 minutes because of Mass, but students were still able to build a strong foundation for what’s next.

Thursday

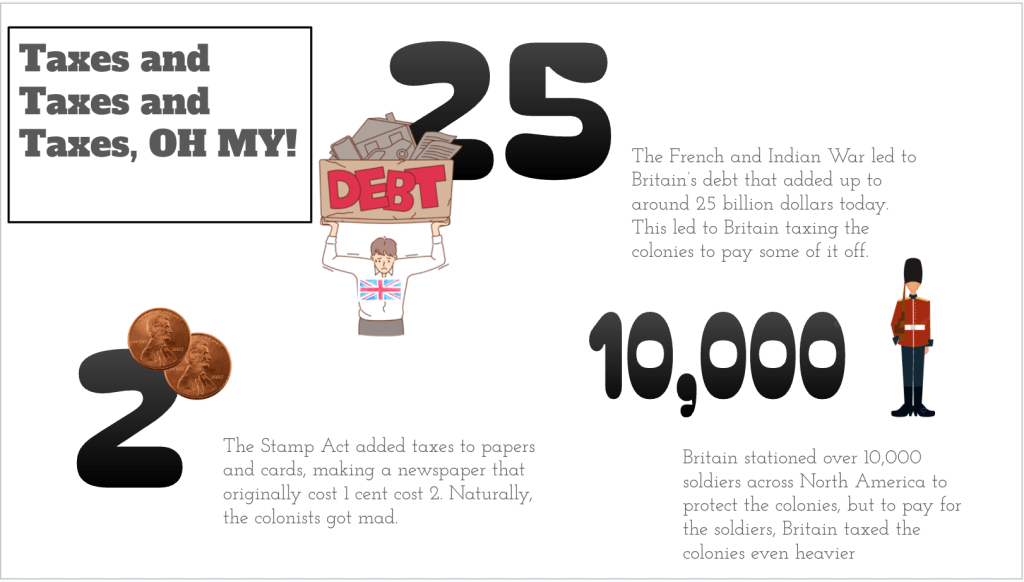

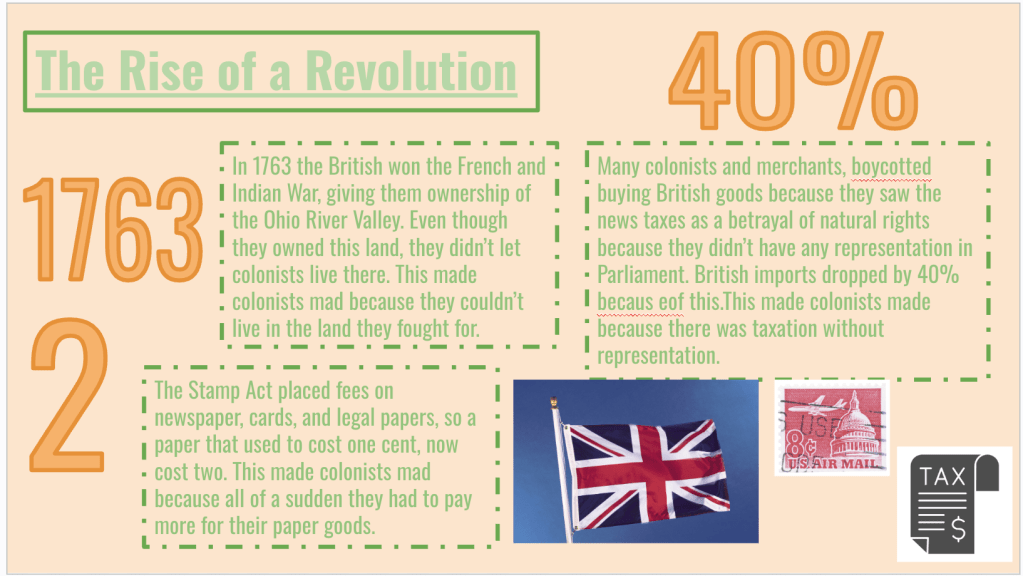

Thursday built directly off where we left our 13 Colonies unit, focusing again on the French and Indian War and how it set the stage for the Revolution. I like using Number Mania to introduce a new unit because it helps place the time period in context and gives students a snapshot of the big ideas ahead.

I also decided that each lesson in this unit will begin with a Thomas Paine quote. He’s the perfect voice for this period and the ideal spark for student curiosity. I introduced him as the top social media influencer of the 1700s and shared our first quote:

A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong gives it a superficial appearance of being right.

The theme of the lesson was about changing relationships. After discussing the quote briefly, we began our Number Mania. I added a twist this time: a Secret Number. It wasn’t written in the text, but it was implied by the context. Students had to think deeply to uncover it. Only three students found it, and it was a great one: zero representation or voice in Parliament.

I didn’t even mention the idea of a secret number before the activity because students can get too fixated on finding it. Instead, I quietly looked for it as I walked around and rewarded those who included it with a Hi-Chew. When one group nailed it, I paused the class to highlight their insight and spark more discussion.

After finishing, students posted what they thought was the most important number from their slide to a Padlet. We ended by replaying our vocabulary Blooket from Wednesday. The results showed solid improvement:

72% to 77%, 59% to 77%, 63% to 73%, 67% to 84%, and 73% to 85%.

Small gains, but big signs of growth.

Friday: The Stamp Act

Friday was all about the Stamp Act. We started with a Blooket again, and the averages told a great story of improvement: 84%, down slightly to 75%, then up to 88%, 89%, and 92%.

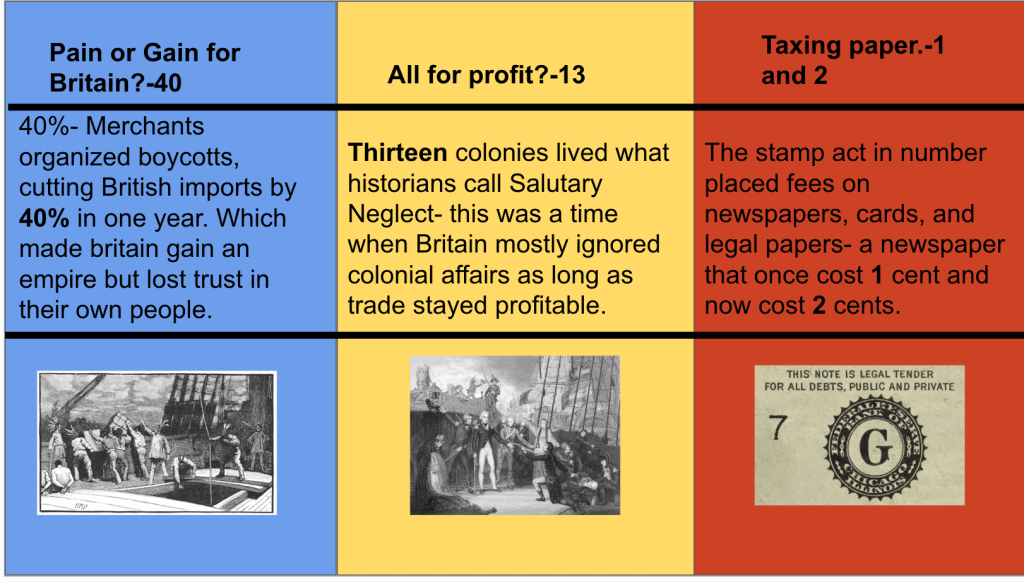

After that, we jumped into a Thin Slide Faceoff. Students created a quick slide on the Navigation Acts with one picture, one word, and one phrase in three minutes. Then we did the same for the Sugar Act. Once finished, groups discussed similarities between the two acts and created another Thin Slide showing the connection. I picked one student per group for a quick five-second share.

Next, students made one more Thin Slide introducing the Stamp Act using a short paragraph. Three minutes, one picture, one word. Simple and fast. They shared within their table groups. I’m starting to like this rhythm of shorter, tighter readings and visuals. It keeps the class moving and gives more time for discussion.

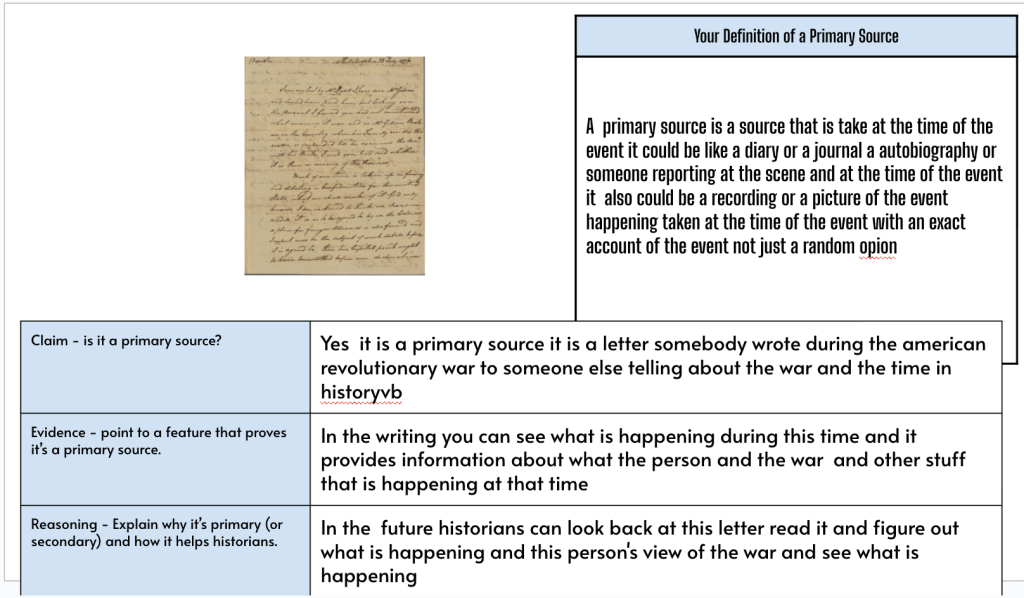

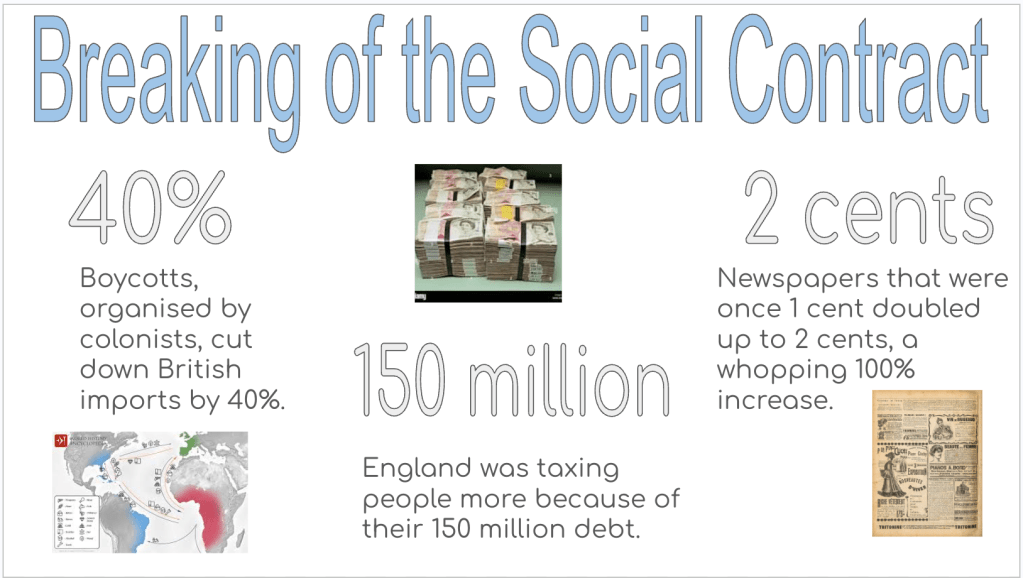

Then we shifted into conversation. I asked, What taxes do we have now? Do you think the Navigation Acts and Sugar Act affected everyone? What about the Stamp Act? That led right into our primary source reading.

We read the actual text of the Stamp Act, which listed the taxes on various items. I gave context on British money: one pound of cheese was four pence, and a steak dinner was one shilling. Students quickly realized how unfair and inconsistent the taxes were. Dice cost ten shillings, playing cards two, and a newspaper could cost as much as food. One student pointed out that colonists probably didn’t have much British currency anyway and wondered where it was even coming from. Great question.

Students then moved into a Sketch and Tell. First, they reread the Stamp Act and starred anything that seemed unfair. The margins filled with stars. Their reasoning was sharp: “It’s all unfair because the colonists had no voice,” one said. Others noted the inconsistencies and the choices people would have to make between eating or staying informed.

To wrap up, students used Emoji Kitchen to create quick images representing taxed items. It was the perfect way to blend creativity and understanding.

A great end to a full week of connection, curiosity, and growing independence.

Lessons for the Week

Monday – Hexagonal Thinking

Thursday – Lesson Introduction – Number Mania

Friday – Stamp Act