This week marked the start of our new unit on the Principles of the Constitution. The focus was not on racing through content, but on building understanding step by step. Each lesson was intentionally designed to move from identifying ideas, to comparing them, and eventually to applying them. By the end of the week, it was clear that slowing down, naming the big ideas, and letting students wrestle with them made a real difference.

Monday

We launched our new unit on the Principles of the Constitution with two guiding questions that will anchor everything moving forward.

- Compelling Question: How did the Founding Fathers strengthen our government and limit its power?

- Supporting Question: What are the principles of government and why are these principles important for American democracy?

We started class the way we often do, with a Fast and Curious on the principles of the Constitution. I intentionally included the word principle itself because it is a major part of this unit. If students do not understand what a principle is, then everything that follows becomes harder to understand. It is not a government specific word, but it is foundational to the thinking we are asking students to do.

The data reflected that starting point. Class averages ranged from 48% to 57%. Not a problem. Just useful information about where students were before we dug in.

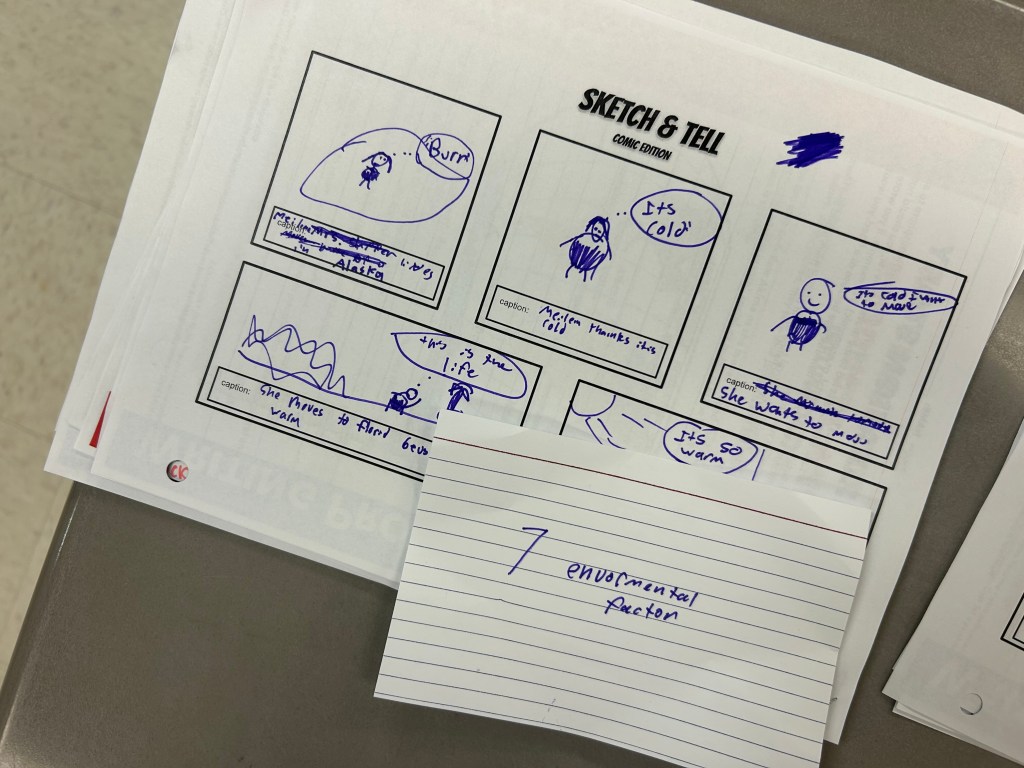

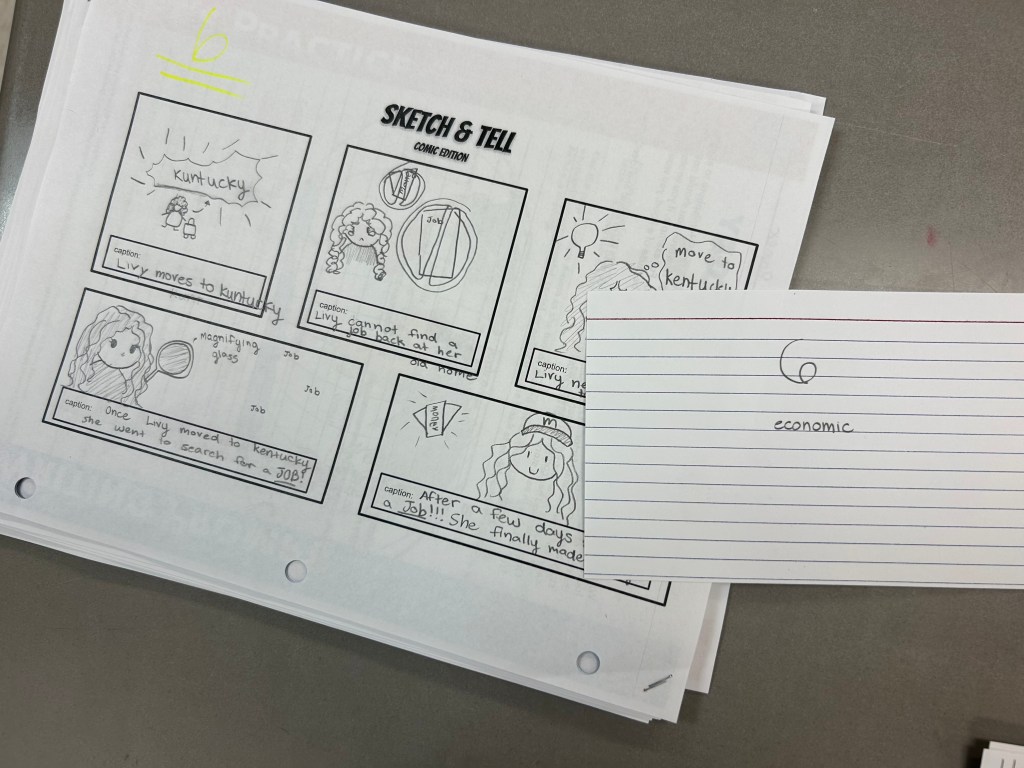

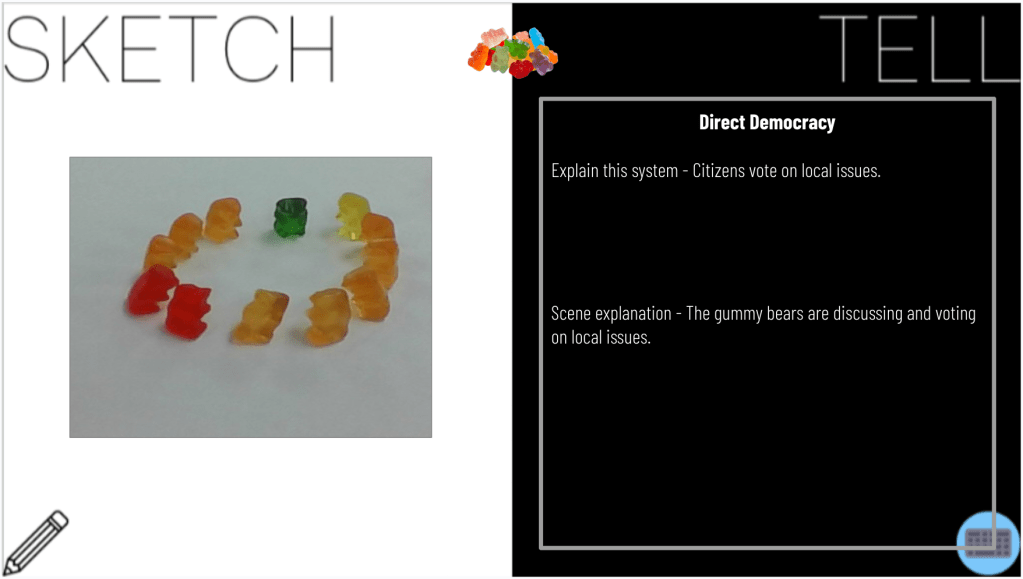

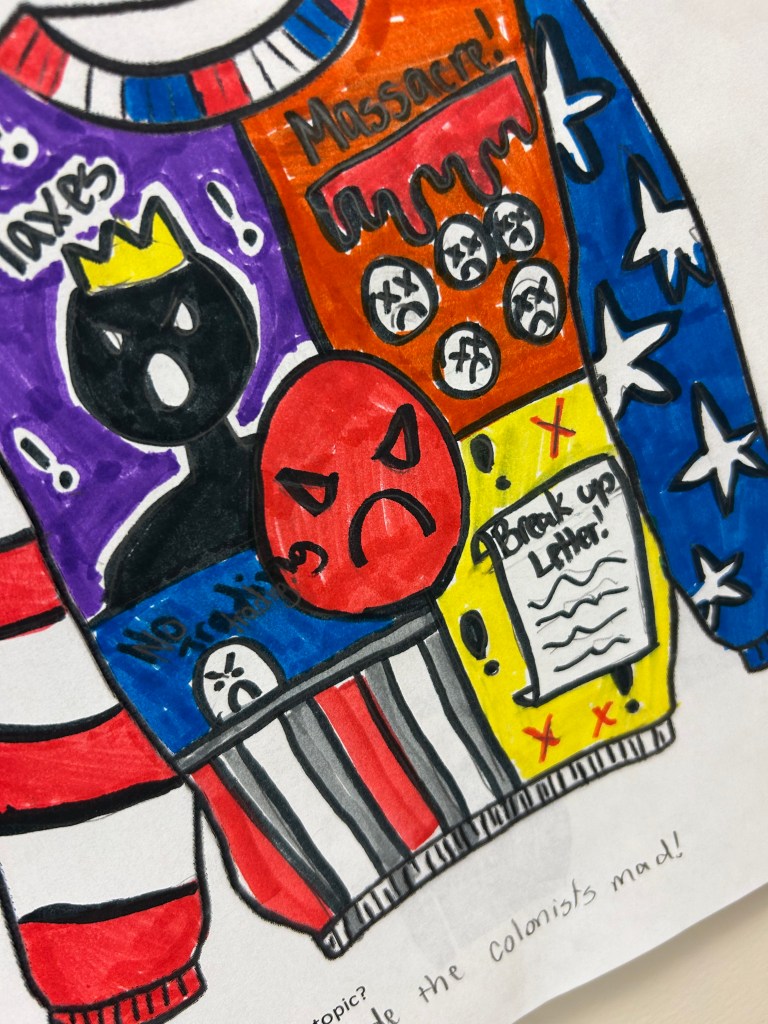

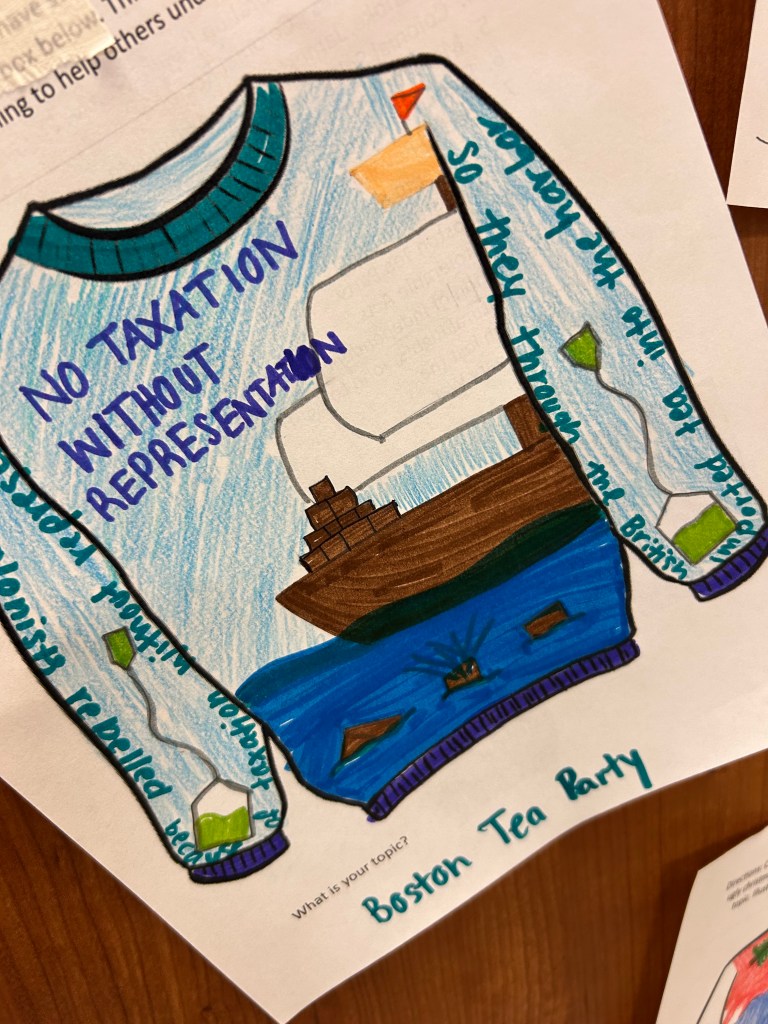

Students then moved into a Sketch and Tell O that my friend Dominic Helmstetter shared with me. As they read, sketched, and labeled, students had to identify each principle, explain what it does, and compare how these ideas work together to balance power. The sketching slowed them down and forced them to translate abstract ideas into something they could actually see and explain.

We finished class with another Fast and Curious, revisiting the same concepts and language.

This time, every class was over 80%.

Same structure. Same routine. Clear growth.

It was a strong reminder that understanding does not come from skipping over big ideas. It comes from naming them, unpacking them, and giving students multiple chances to interact with them in different ways.

Wednesday

On Wednesday, I busted out Curipod and paired it with a Frayer Model.

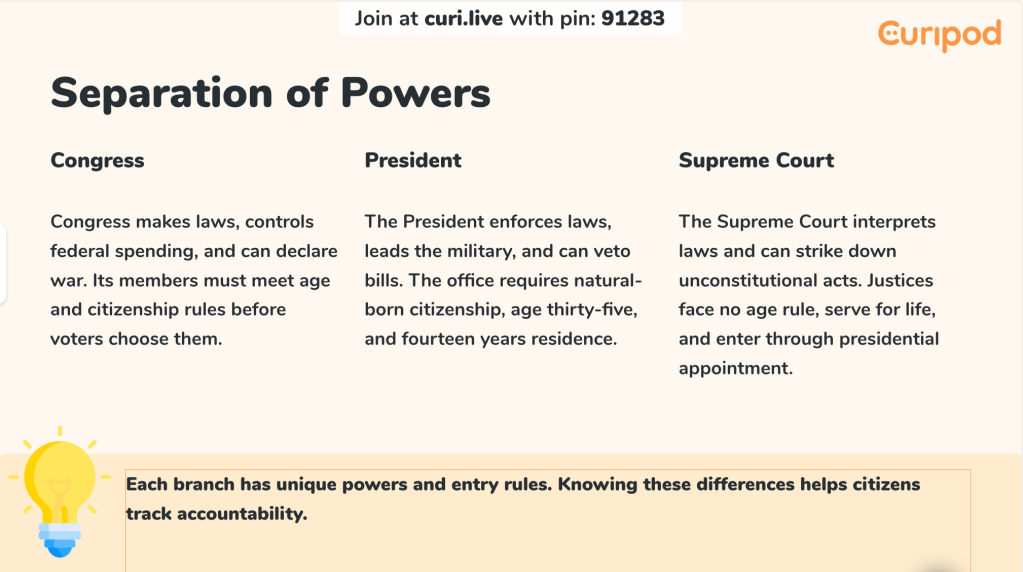

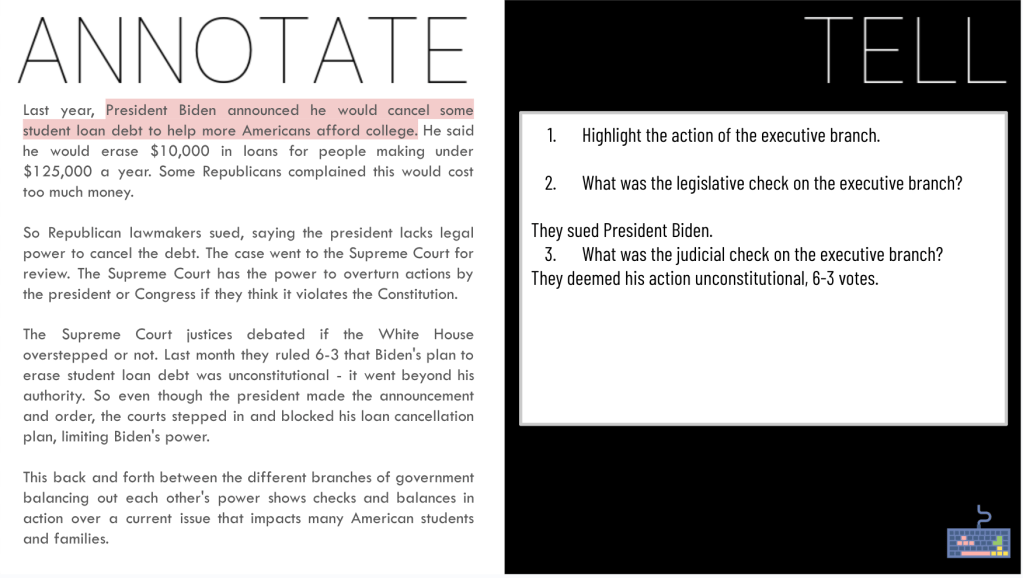

I used Curipod to build an interactive lesson on separation of powers with the main question driving everything: What is the separation of powers and how does dividing government into three branches limit the power of any one branch?

The Curipod lesson included a mix of questions that pushed students to think instead of just recall. Students were asked to describe separation of powers in their own words, think back to the Articles of Confederation and identify what was missing, explain a real example of how a president could limit Congress, and name powers of Congress without falling back on “making laws.” Those prompts mattered because they forced students to apply ideas, not just label them.

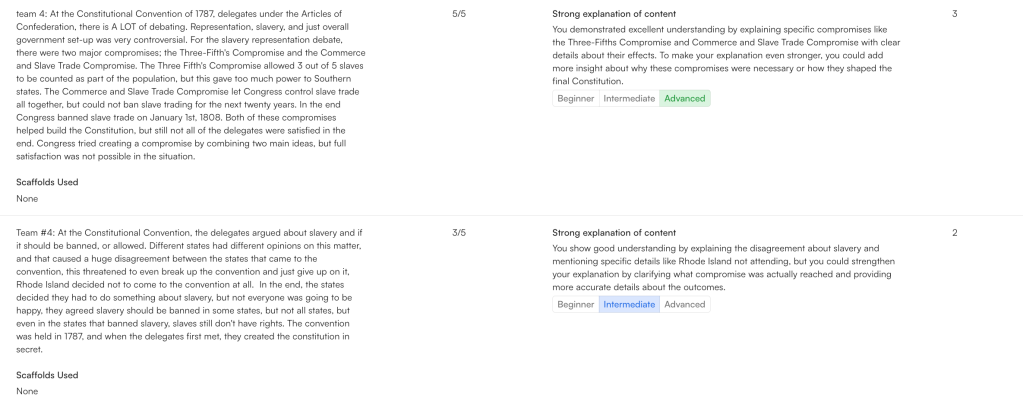

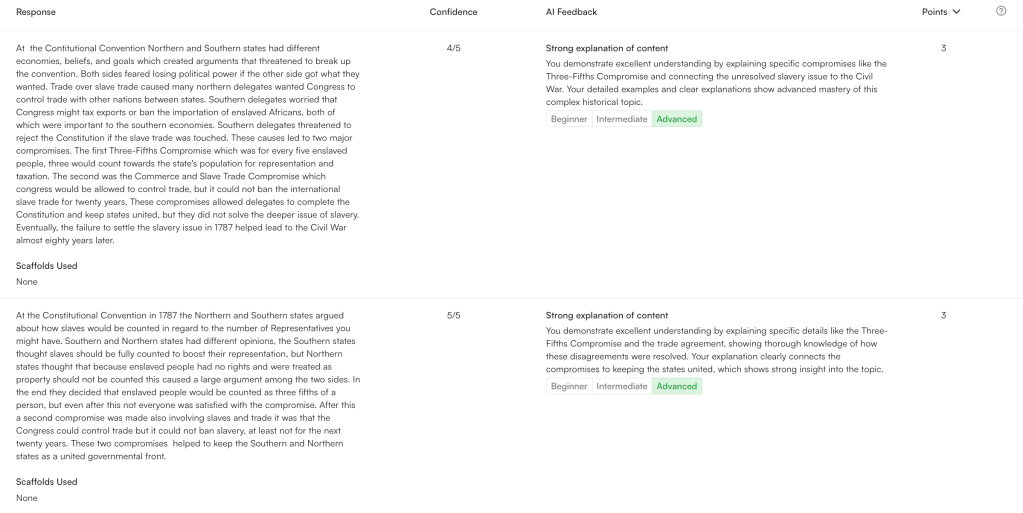

One feature that stood out was the AI feedback for student writing. Students received immediate feedback on whether they answered all parts of the question, used a specific example, and clearly explained how that example showed government power being limited. This was something new, and the kids genuinely seemed to enjoy it. It gave them quick direction without stopping the flow of the lesson.

As we worked through the Curipod, students used a Frayer Model to take notes on each branch of government. We filled it in together as we went, focusing on powers, responsibilities, and why those differences exist. One thing that surprised me was how many students did not know the three branches or their basic functions. This is content students are usually exposed to somewhere between third and fifth grade, but it was clear that many were missing pieces. That made slowing down even more important.

We also paired the Curipod with retrieval practice. We started class with a Blooket on branches of government and separation of powers. The starting averages were 61 percent, 57 percent, 48 percent, 58 percent, and 61 percent. After the Curipod and Frayer work, those averages jumped to 75 percent, 74 percent, 81 percent, 74 percent, and 82 percent.

That growth reinforced something I keep coming back to. Students do not need more tools. They need the right tools used with intention. Clear questions, structured thinking, and repeated chances to revisit ideas made the difference.

Thursday

Thursday was where the process really started to show itself.

I handed out a triple Venn diagram and explained the purpose clearly. When I focus on lesson planning and design, I want a process to unfold that helps us get where we are going. The Frayer Model paired with Curipod and the Blooket earlier in the week served as our DOK 1 work. That was about identifying, defining, and understanding the basics.

The triple Venn diagram was the DOK 2 move.

Students had to recall what they knew about each branch of government and then compare them. This pushed them beyond listing facts and into thinking about similarities and differences. They worked together extremely well, sharing ideas, debating where things belonged, and thoughtfully trying to come up with meaningful overlaps instead of surface level answers.

I gave students 15 minutes to complete the task, and the conversation in the room was exactly what I was hoping for.

Afterward, we went back to Fast and Curious on Blooket. This time the class averages jumped to 82 percent, 84 percent, 85 percent, 80 percent, and 92 percent. The one class that landed at 80 percent was also the class that had the least amount of time to discuss and reflect during the Venn diagram work, which felt like an important reminder. The talking and thinking mattered.

At the end of class, I handed out a project to wrap up the unit where students would turn a branch of government into a superhero. This is something I have done for years, but did not do last year.

By the end of the day, though, I knew I was going to change my mind about that plan on Friday.

Friday

The more I thought about the branches of government superhero project, the more I realized it was not time yet.

I made a teacher move Friday morning and shifted to checks and balances. There were two reasons. First, there was no realistic way students were going to finish the superhero project in class, and I had zero interest in assigning weekend homework during the Super Bowl. Second, the superhero idea makes a lot more sense once students actually understand checks and balances.

Thankfully, I already had a checks and balances lesson ready to go from last year. When I went to my blog to grab it, the link showed up as nonexistent. I am not sure who it was in the EduProtocols Facebook group, but someone had shared it, and I was able to copy it quickly. So thank you to whoever preserved and shared that lesson.

I love this checks and balances lesson because it has a clear progression.

We started with a Rock Paper Scissors tournament and I reminded students that our government was designed the same way. No branch is better or more powerful than another. Each one has strengths and weaknesses.

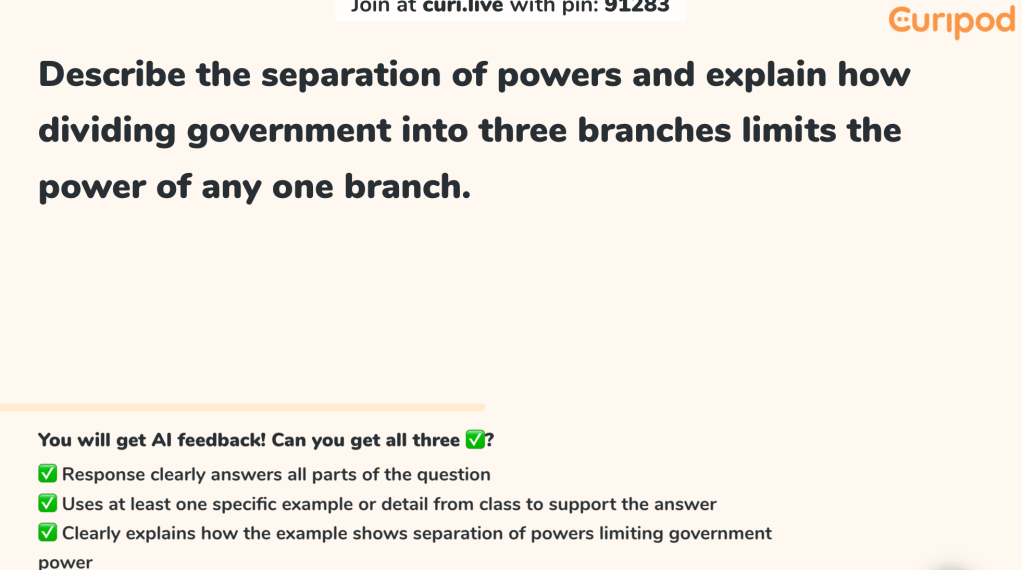

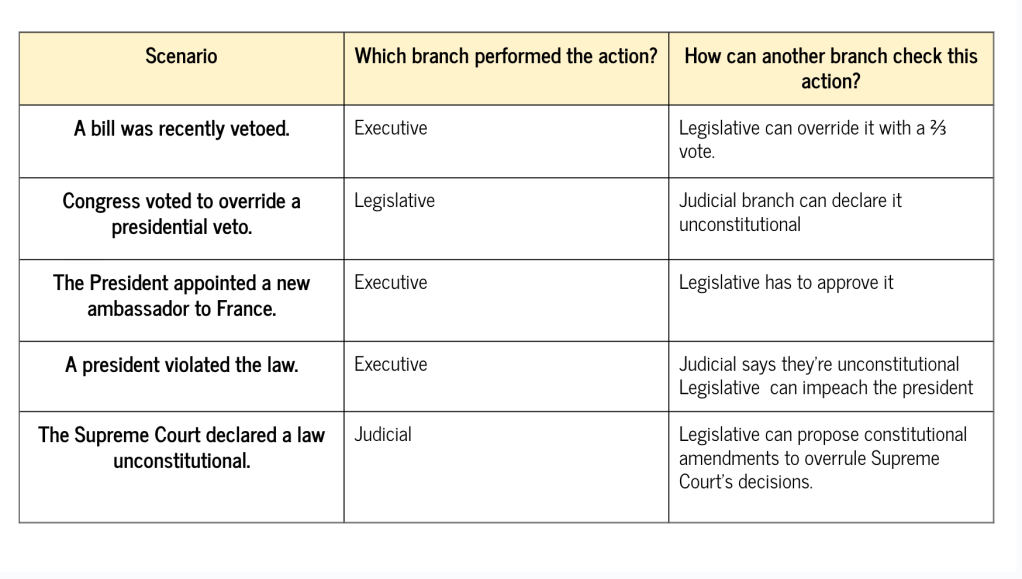

Next, I handed out a checks and balances chart. Students used the chart to work through a diagram where they read a scenario, identified the branch involved, and then identified how another branch could check it. This was a DOK 1 task focused on understanding and identification.

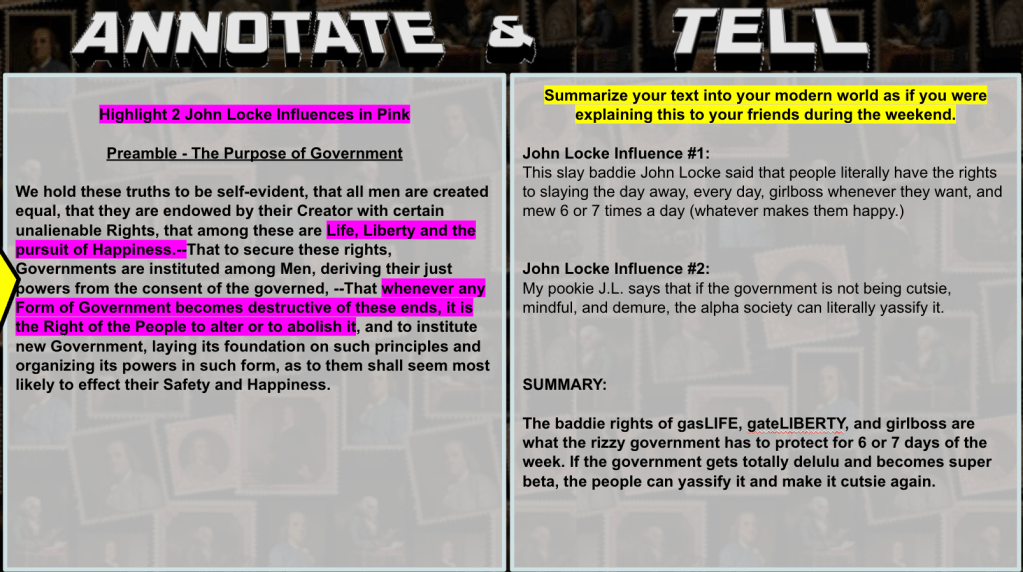

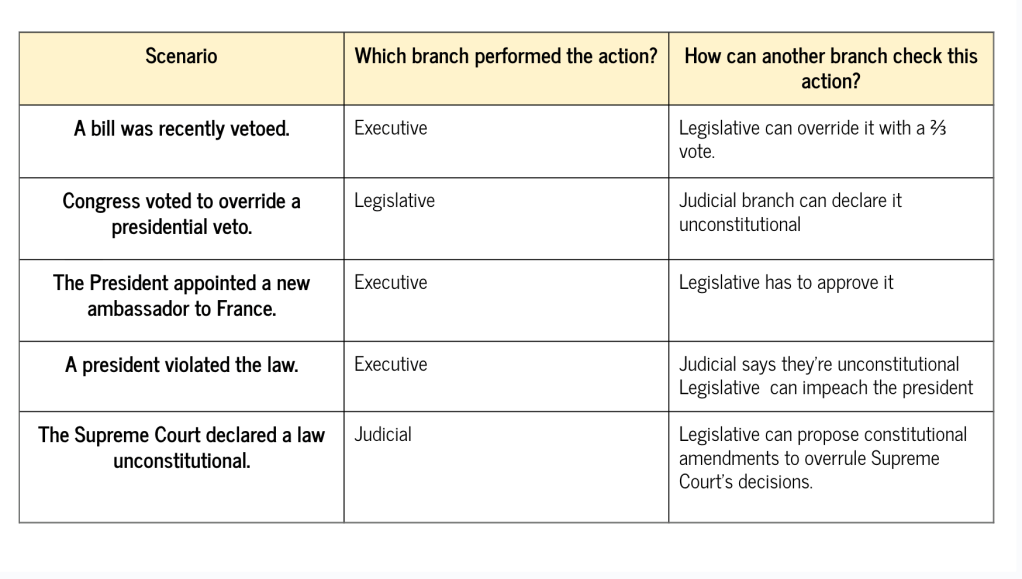

After that, students moved into an Annotate and Tell activity using real news scenarios. This time, they had to identify an executive action and then explain how the legislative and or judicial branch could check it. This pushed the thinking a step further and made the idea of checks and balances feel more real.

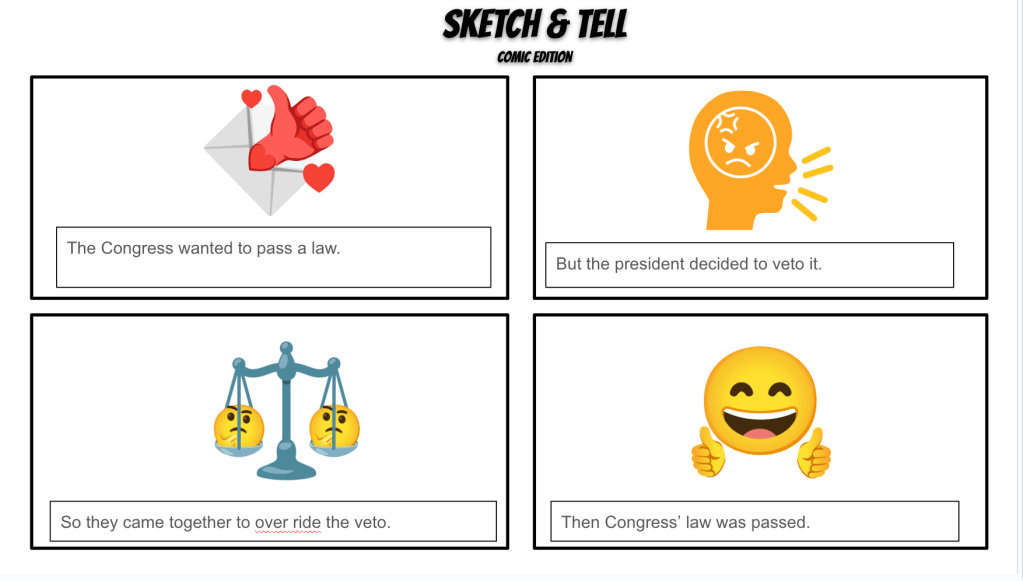

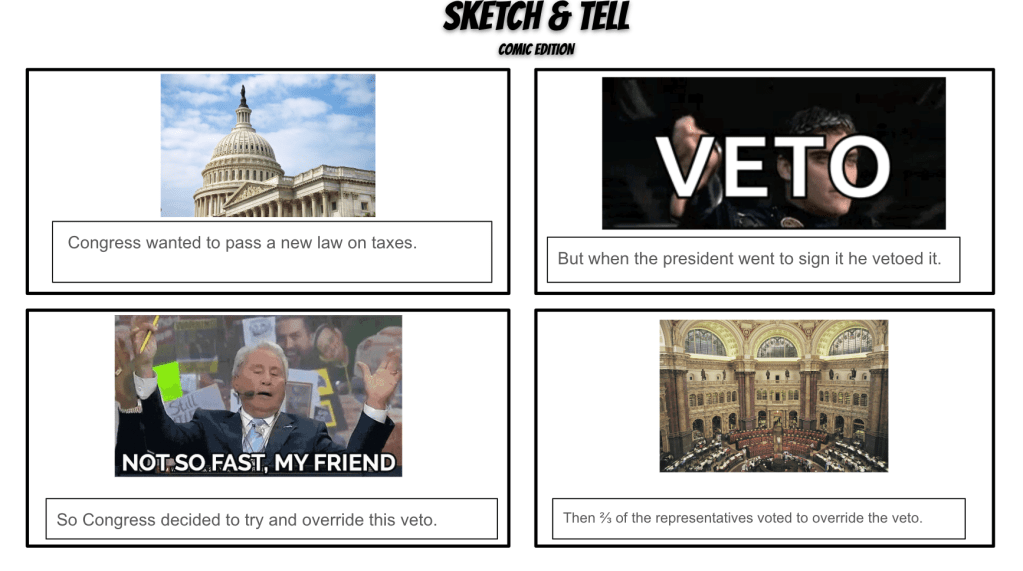

The final piece was a Sketch and Tell comic using Somebody, Wanted, But, So, Then. Students created their own checks and balances scenario and added visuals to match the story.

Only one class had time to finish with a Blooket, and that class ended with an 87 percent average.

By the end of the day, it was clear that pushing the superhero project back was the right call. Students needed this understanding first. The creativity can come next week.

Lessons This Week

Monday – Principles Sketch and Tell-O

Wednesday and Thursday – Curipod Separation of Powers, Frayer, Venn Diagram

Friday – Checks and Balances