I’ve been watching Ken Burns’ new documentary, The American Revolution, and it hit me just how much is packed into this era. Abstract ideas. Complicated politics. Dozens of events. And honestly, the way I used to teach it wasn’t doing anyone any favors.

My old approach was pretty typical: start with some vocab, squeeze in the French and Indian War, sprint through every tax over 2–3 days, toss in salutary neglect somewhere, then protests, then the Boston Massacre as a one-off, then the Tea Party and Intolerable Acts, and finally the Declaration and natural rights. It worked… but there was no flow. Too many disconnected parts. The cognitive load was just too much.

This year, I decided to take a completely different path.

I treated the French and Indian War as the ending to my 13 Colonies unit, framing it as a rivalry gone bad. Then, instead of opening the Road to Revolution with new content, I started with review of the consequences of that war and the breakdown of salutary neglect. I still taught vocabulary up front, but this time I wanted the unit to feel like a story told through the voices of the people who lived it.

We kicked things off with the Stamp Act by reading the actual wording. Kids debated fairness using the colonists’ own language. I even taught the difference between a pence, a shilling, and a pound because if you want them to understand the argument, you have to let them stand inside it.

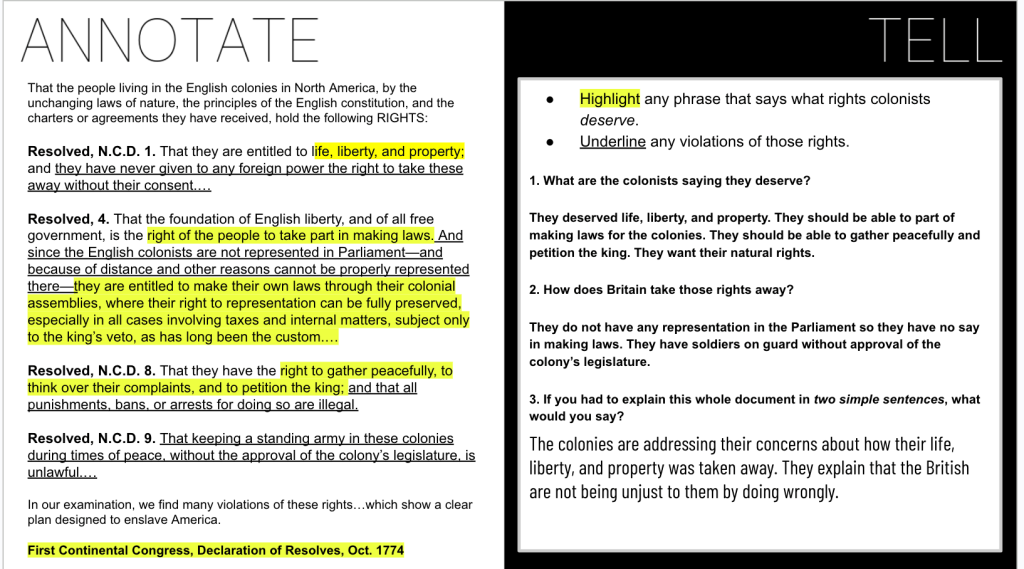

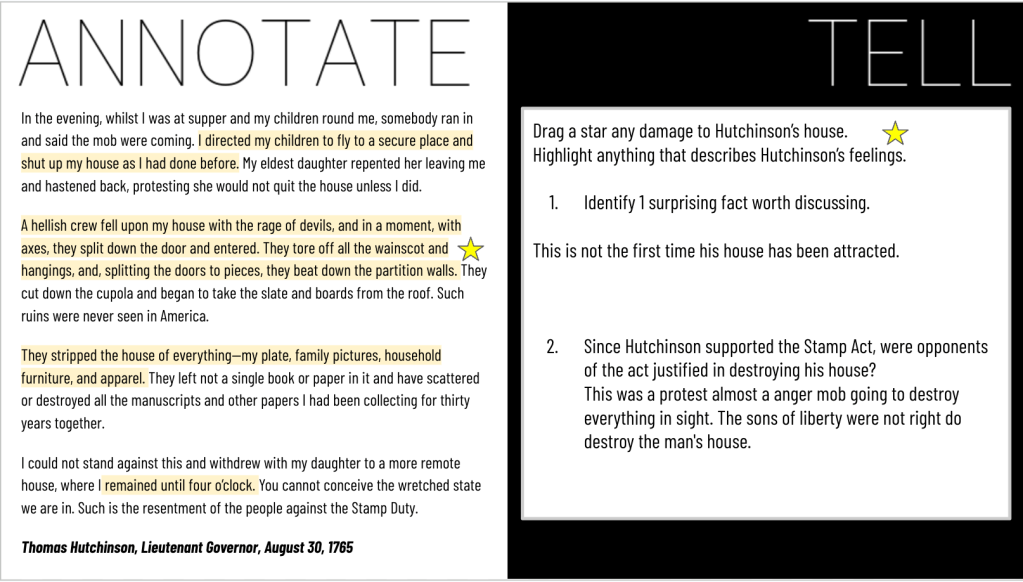

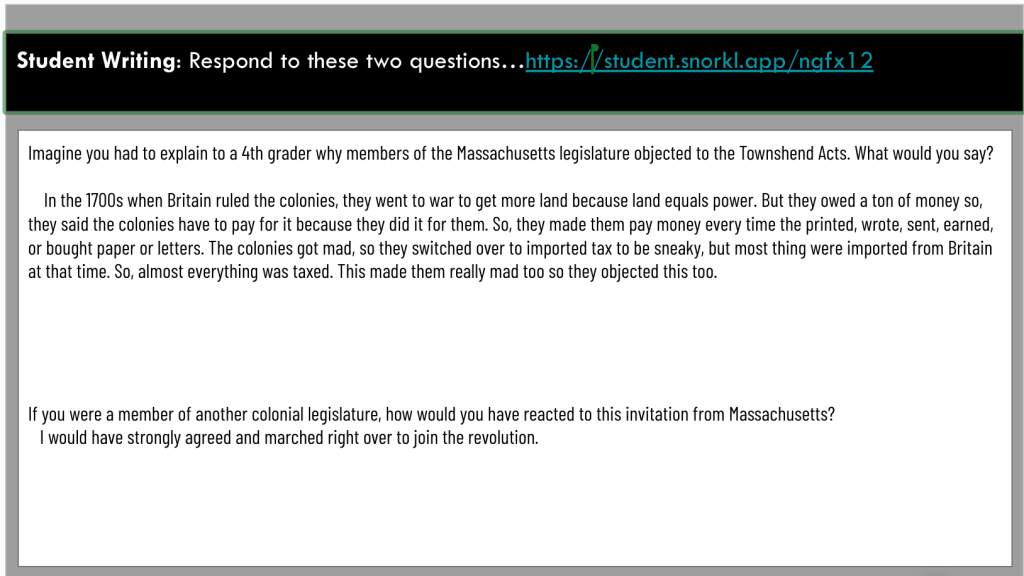

From there, we looked at protests and reactions through the eyes of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson. Same people, same thread, same narrative. Then we moved into the Townshend Acts and Adams’ Massachusetts Circular Letter. That’s also when I introduced natural rights, not waiting until the Declaration of Independence. Life, liberty, and property were already shaping colonial arguments long before 1776.

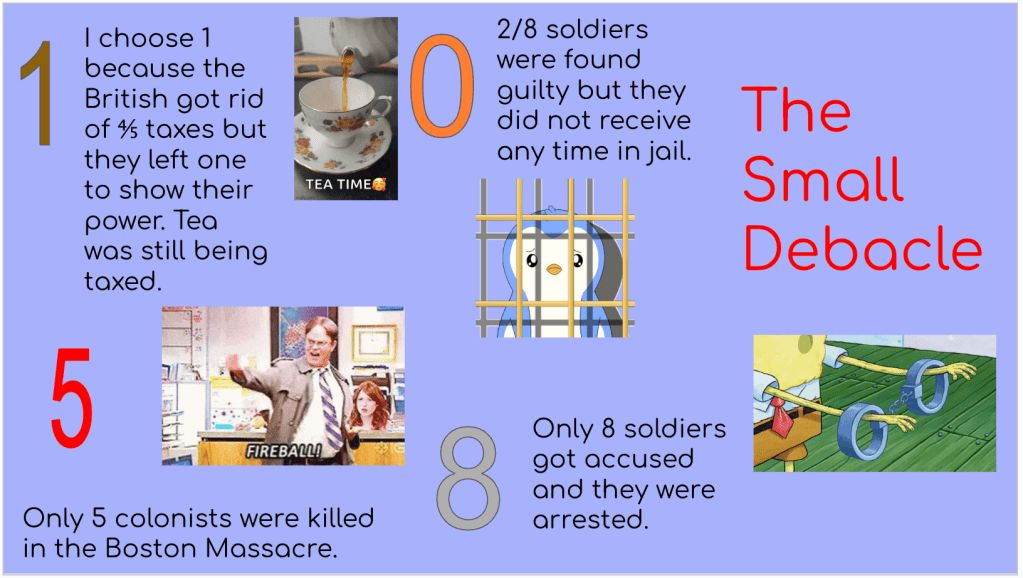

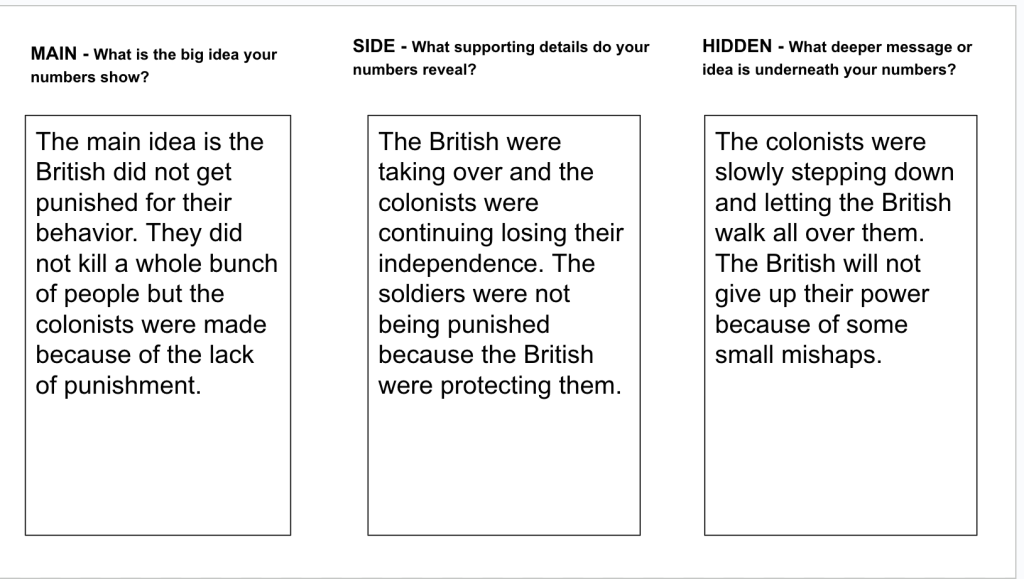

When we got to the Boston Massacre, it finally clicked for them: “If natural rights include life… what happens when government ordered, British soldiers fire into a crowd?” The story built itself.

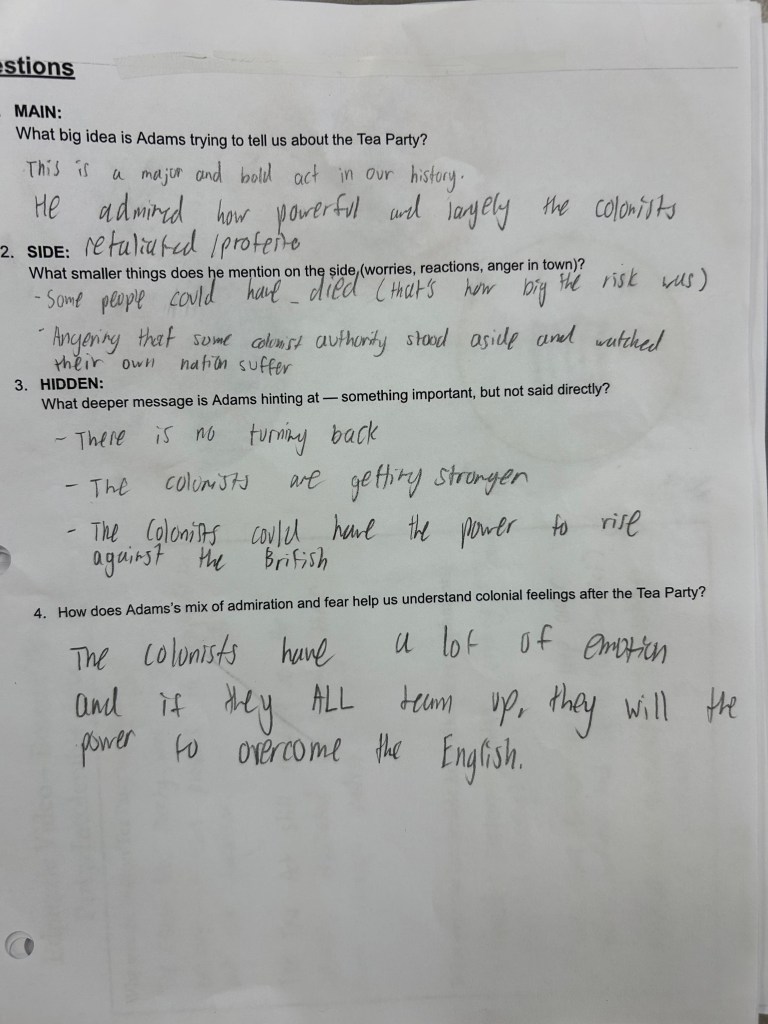

Then we hit the Tea Party and Intolerable Acts using a diary entry from John Adams where he basically predicts the crackdown and knows war is on the horizon. Finally, we closed the chapter with the First Continental Congress and their Declaration of Resolves. Background reading to primary source to short, purposeful chunks. As my friend and co-author Scott Petri always said: “Don’t make your class death by 1,000 primary sources.”

In the end, the kids didn’t just remember events, they followed a coherent story told by the people living it. And that made the culminating question feel earned:

Why did British subjects go from being loyal to fighting their own government?

This new approach felt clearer, more human, and honestly… more teachable. And watching students connect the dots on their own reminded me why I love this job.